WHAT REMAINS | Alexandra Miner

© What Remains. Alexandra Miner. Spring 2021 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine

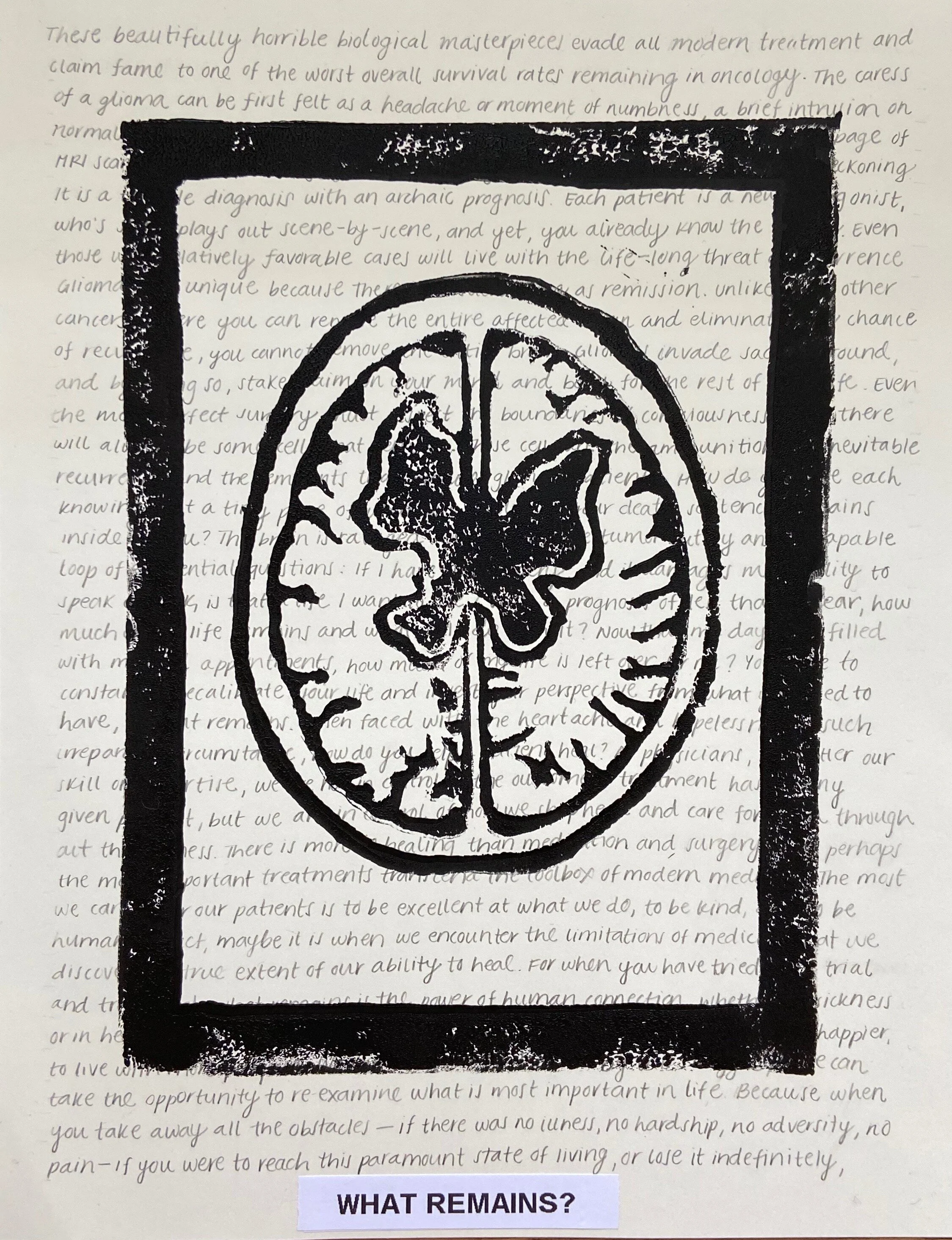

These beautifully horrible biological masterpieces evade all modern treatment and claim fame to one of the worst overall survival rates remaining in oncology. The caress of a glioma can be first felt as a headache or moment of numbness, a brief intrusion on normal life. But once it has entrenched, its presence quickly explodes into a rampage of MRI scans, awake brain surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and all-around life reckoning. It is a terrible diagnosis with an archaic prognosis. Each patient is a new protagonist, who’s story plays out scene by scene, and yet, you already know the ending.

*

Even those with relatively favorable cases will live with the life-long threat of recurrence. Gliomas are unique because there is no such thing as remission. Unlike most other cancers, where you can remove the entire affected organ and eliminate any chance of recurrence, you cannot remove the whole brain. Gliomas invade sacred ground, and by doing so, stake claim on your mind and body for the rest of your life. Even the most perfect surgery must respect the boundaries of consciousness, and there will always be some cells that remain. These cells are the ammunition for inevitable recurrence and the remnants that plague glioma patients.

*

How do you live each day knowing that a tiny piece of what will likely be your death sentence remains inside of you? The brain is ravaged not only by the tumor, but by an inescapable loop of existential questions: If I have this surgery, and it damages my ability to speak or walk, is that a life I want to live? With a prognosis of less than a year, how much of my life remains and what will I do with it? Now that my days are filled with medical appointments, how much of my life is leftover for me? You must constantly recalibrate your life and invert your perspective from what you used to have, to what remains.

*

When faced with the heartache and hopelessness of such irreparable circumstance, how do you help a patient heal? As physicians, no matter our skill or expertise, we are not in control of the outcome a treatment has for any given patient, but we are in control of how we shepherd and care for them throughout their illness. There is more to healing than medication and surgery, and perhaps the most important treatments transcend the toolbox of modern medicine. The most we can do for our patients is to be excellent at what we do, to be kind, and to be human. In fact, maybe it is when we encounter the limitations of medicine that we discover the true extent of our ability to heal. For when you have tried every trial and treatment, what remains is the power of human connection.

*

Whether in sickness or in health, the truth is that we are all striving to live. To live better, to live happier, to live with more purpose. We can choose to be defined by this struggle, or we can take the opportunity to re-examine what is most important to us in life. Because when you take away all of the obstacles—if there was no illness, no hardship, no adversity, no pain—if you reach this paramount state of living, or if you lose it indefinitely, what remains?

Alex Miner is a second year medical student at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine in Roanoke, Virginia. She is passionate about all things art and science and spends her free time reading, figure skating, and adventuring. Prior to medical school she completed her masters thesis on genetic mechanisms of drug resistance in glioblastoma and she plans to go into neurosurgery to pursue a career as a physician-scientist and writer. Her piece, What Remains, was inspired by a series of interviews with glioma patients, who she hopes will be the first of many she is privileged to care for and learn from.