WELCOME TO INTIMA: A JOURNAL OF NARRATIVE MEDICINE

© The Window by Esha Sawan. Acrylic.

In this new issue of Intima, we have the honor once again of bringing you some of the best stories on medicine, caregiving and healing. We are reminded how healthcare providers and patients reflect on—and tend to—the stories of care, loss, illness and recovery with incredible care. It’s an idea gracefully expressed in “The Window” (above) by Esha Sawant, a third-year medical student at Stony Brook University, who sees art “as a way to create intentional space for reflection and to capture striking moments in medicine.” We welcome you to pause for a moment in your frantic, over-scheduled day to take in a poem or a Field Notes essay. Or do a leisurely read of any of this issue's narratives and enjoy their depth, humor and originality.

Find moments of reflection with our inspiring new anthology

Intima has been publishing stories for over a decade, and we’re happy to share good news: Where It Hurts: Dispatches from the Emotional Frontlines of Medicine, an anthology of essays, short stories and poetry culled from our archives, will be published on March 24th, 2026. Rita Charon wrote the stirring foreword to the collection. These pieces, and the ones in our Fall issue, beckon with quiet gravity.

We would be honored if you consider

pre-ordering Where It Hurts. We feel it’s essential reading for everyone who wants to read moving poems, essays and short stories about caregiving, empathy, health care, vocation and all of the emotions we experience in our everyday lives.

How to love—especially in the face of difficult diagnoses—is at the heart of Joanna Sharpless’ essay “Perfect.” In a reflection about learning her child has a congenital sensorineural hearing loss, the palliative care physician takes us through the recurring stages of discovery, mourning and acceptance, as she discovers “this fact about her hearing will be one of ten, then one hundred, then a thousand important things about her.” Sharpless’s revelations are eye-opening, allowing you to see an new vision of “what is perfect.'“

Collecting life’s memories and mementos highlights the shared responsibility of writers and caretakers: to take the time to notice and bear witness. Primary care physician Nathan Rockey’s essay “Passing the Touch,” a beautifully crafted tribute to his physician-grandfather, embodies this ethos. His grandfather’s wish for his loved ones to “find a little rock or stone that [reminds] you of me. Then, once a day, hold it tightly in your hand and say, be well” carries deep resonance as we trace the natural history of our lives through small objects and gestures.

Readers can feel these tactile connections reading “Stroke or Not Stroke,” neurology resident Rebecca Ripperton's Field Notes essay. Ripperton juxtaposes the responsibility of diagnosing strokes with her search for an authentic lapis-blue Le Creuset Dutch oven. Stroke or not stroke? Real or not real? She points out the tensions between high-stakes objective evaluation and facing the human behind the diagnosis when she finds herself “at times more certain of the contours of a patient’s carotid vasculature than of their age or name.” Readers feel the metaphorical cold metal and hefty load as she writes: “In medicine there is no shelf, no return; only the responsibility of carrying what is real and learning, slowly, how to bear its weight.”

© Departure & Return: Visualizing Ethical Tensions in Geriatric Care by Madison Zhao. Ink pen, marker and watercolor on paper

Our nine provocative short stories range in topic, from medical training, in the amusingly futuristic "I Am Hamm," by physician Austin Valido, to first job confusion in the summer of '98 on a Navajo reservation in New Mexico ("Sammy's Still Screaming") by pediatric surgeon Ron Turker. In her singular short story “Mirella, ” Annette Leddy, an oral historian and fiction writer, explores late-stage memory loss and the impact of aging on a person’s life and relationships. We follow the hollows of Mirella’s mind as she navigates her relationship with her husband Roger, whom she no longer recognizes, during their residence at a memory care unit. We travel through the layers of her memory, unmoored, as she tries to rediscover herself and grapple with what it means to love and be loved.

© CHEMO-od by Annunziata Tricario. Acrylic

In this issue, we also received moving pieces from the patient perspective. In a series of evocative self-portraits, titled “CHEMO-od,” contemporary artist Annunziata Tricarico details a personal journey of resilience while navigating a breast cancer diagnosis. Using bold colors and blending abstract patterns with recognizable motifs, these portraits capture the intensity of navigating life with a serious illness. Tricarico invites the viewer in by representing the alienation of self, asking what it means to rediscover the body and track its transformations.

Those feelings of embodiment and disembodiment are also evident in “Edna," retired neurologist Ann Bebensee’s tale about the relationship with her stoma. Bebensee writes with unflinching honesty and wit about what happens when bodies are changed and feel separate from the self, yet remain connected: “[Edna] felt alive, apart from me, but still irrevocably attached to me.” As we follow along, we can’t help but laugh and be surprised and transformed.

Poetry plays its part in helping us as readers and clinicians to understand the other. “I am a museum,” writes Joseph Zarconi, a retired nephrologist and active educator, in "American Sonnet for an Addict." This poem humanizes addiction and the person beyond a constellation of symptoms and physical exam findings, revealing the tragedies that can precipitate substance use. The play on the word “liver” as both an organ and as “one who lives” reminds healthcare providers to always empathize with patients rather than judge or blame. In the subtle and effective poem "Not One of Us," University of Michigan medical student DeMarcus Burke uncovers the feelings that surface when experiencing racism coming from an unexpected place.

To tend to something or someone is to take care of, to pay attention, to turn the mind toward, to stretch and then extend. This is what we hope you will do as you read—just as these authors have so generously reminded us how, every day, we tend and are tended to.

—Sophia Li for the editors of Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.

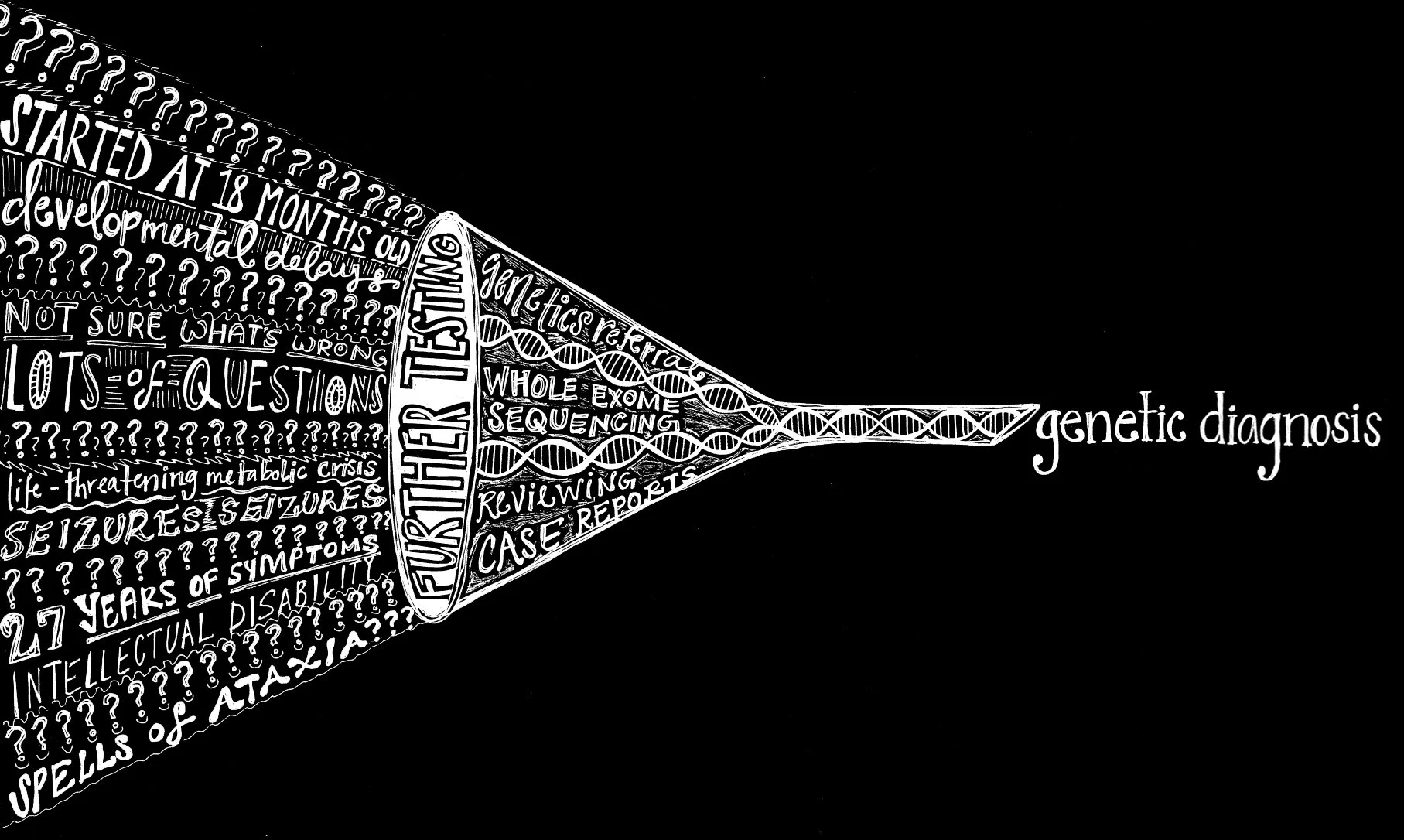

© Genetic Diagnostic Funnel by Sujal Manohar. Ink.

“For a medical school capstone project, I conducted interviews with families impacted by genetic conditions. The piece was inspired by a patient’s family who searched for answers for twenty-seven years before receiving a genetic diagnosis.”