I recently read a remarkable poem in the The Iowa Review called "Post NICU Villanelle" by Joyelle McSweeney. The piece is an excellent example of the way chaos can be reimagined, the way feeling can be reined in, organized, and expressed with language. Every image in this poem is sharp, poignant and abbreviated. It's a mournful and deeply beautiful statement about a mother's loss.

I’ve long been fascinated by the way structure informs poetics and the practice (and in this case—reception of medical care). In my piece “Field Notes on Form,” I extol the ways in which linguistic structure has the remarkable ability to organize our thoughts, increase our signal within the noise, and etherealize the mundane. In “Post NICU Villanelle,” Joyelle McSweeney uses language not only to remediate the chaos of loss and of leaving but also to deconstruct both the poetic form and herself.

The title of her piece suggests the format of a villanelle, which is a French poetic form consisting of 19 lines. The stanzas are arranged into three line segments and the poem ends with a quatrain. The first and third lines of the poem are repeated and form the last two lines. The purpose of the repetition is to convey a sense of obsession and rumination over a concept or a consuming thought.

McSweeney, to great effect, refuses the confines of a strict repetition of lines and instead employs a looser interpretation of tightly associated images, the repetition of the concept of “evening” and “spring.” In this way, she not only organizes and expresses her grief, but deconstructs the structure of the villanelle in the same way that she deconstructs her own grief at the loss of her newborn.

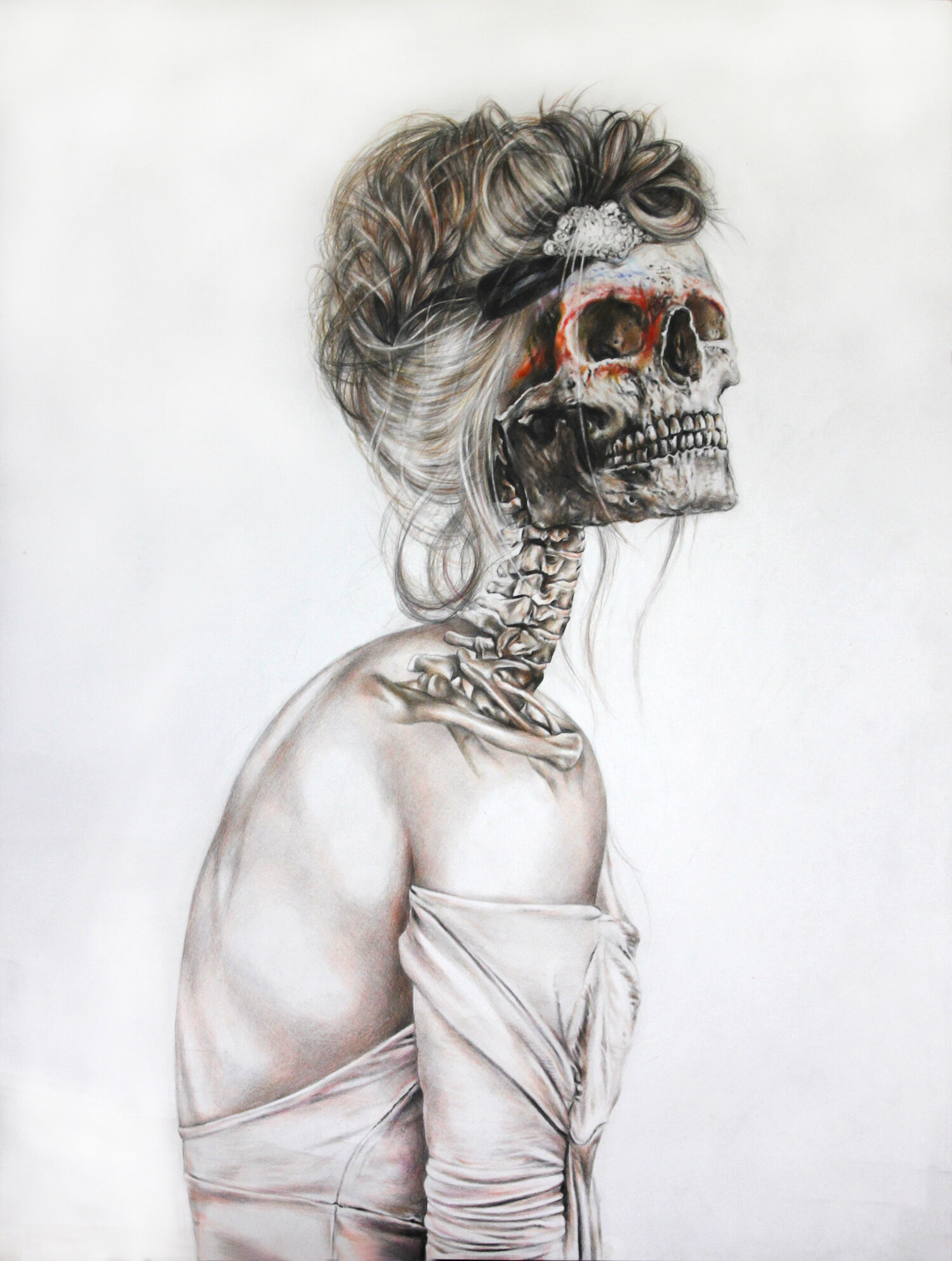

I am reminded of Meagan Wu’s stunning portrait “The Anatomy of the Vogue” (Spring 2017 Intima), which reminds us that the experience of illness, and the practice of caring for those who are ill, is often a process of self dissection, deconstruction and the realization that underneath our exteriors we share the common language of a human body, carrying with us its weaknesses and its virtues. In this way, poetic form is our way of constructing and deconstructing, burying and, if the poet is exceptional, unearthing, the common language that unites us all.

Selene Frost is a writer as well as a chief resident in general surgery. She's spent the last year developing and implementing a narrative medicine curriculum for her surgical residency program involving weekly prompts for clinical reflection and quarterly didactic and discussion sessions.

Her interests include the intersections between art and medicine and the examination and rewriting of surgical culture. She believes that the future of medicine lies in the revision of the narratives that hold us back and the telling of stories that move us forward.

She hopes to dedicate her career to the training of empathetic and humanistic surgeons. Her creative work has been published in Oddball Magazine. She can be found on Instagram @selenefrostpoetry