One day, long ago when I was a boy, I waited for my brother outside Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital. Yet another plastic surgery was needed to correct a car accident trauma to his face. I glanced up to the towering figure of Our Lady above the hospital and read this inscription below her feet: “The body is often curable. The soul is ever so.”

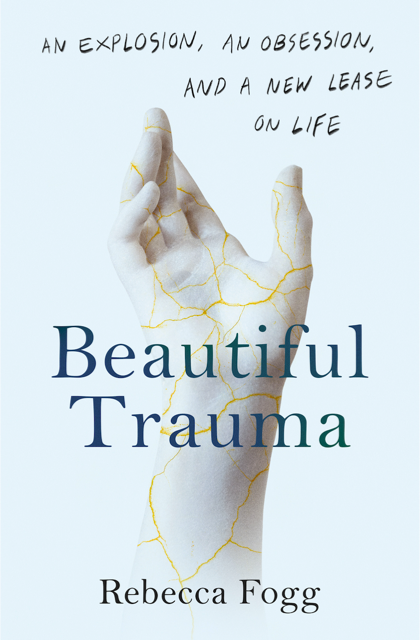

I recalled this inscription often while reading the just-published book, Beautiful Trauma: An Explosion, An Obsession and a New Lease on Life, Rebecca Fogg’s story of recovery from a freak, in-home accident. Her story is alternately harrowing, humorous and enlightening. Late one night as she was preparing for bed, she flushed a high-pressure toilet and it exploded. Suddenly a piece of porcelain tore into her right wrist, partially severing her dominant hand. What follows is a tour of her body and spirit in recovery.

Beautiful Trauma: An Explosion, An Obsession and a New Lease on Life is remarkable for its depth and clarity when it delves into the science and anatomy of the hand. It is also honest in its appraisal of how her privilege allowed her to receive extraordinary medical care. At the same time, it is a self-reflective memoir of how the injury caused her to reassess her life-long trait of independence by learning to rely on others. We learn a lot about her eminently curable spirit, and the network of social and familial connections that renewed it.

Fogg is no stranger to trauma, having survived the terrorist attack on 9/11 as she was working in the North Tower. She uses this incident to note the “meta-tragedy” of trauma: she asserts that those with higher levels of education, more financial resources and strong social networks are better able to handle trauma than those without such resources. Accordingly, she admits that her privileged position was a saving factor in her recovery from both 9/11 and the present trauma.

In 2008, Rebecca Fogg walked away from her New York life and successful career in financial services to move to London, where she co-founded the Institute of Pre-Hospital Care at London’s Air Ambulance and continues to work, write, and learn Scottish fiddle. A graduate of Yale University and The Harvard Business School, she spent five years (2014-2019) researching and writing about healthcare with renowned Harvard Professor Clayton Christensen, author of The Theory of Disruptive Innovation. Beautiful Trauma: An Explosion, an Obsession, and a New Lease on Life (Avery, Penguin Random House) is Fogg’s first book. It was awarded the 1029 Royal Society of Literature Giles St. Aubyn Judge’s Special Commendation for work in progress.

What is distinctive about this particular narrative about trauma is its sense of balance in telling it: Fogg notes that there are innumerable responses to recovery, and she wisely avoids turning this story into a “how-to-survive-a-trauma” manual. This is no misery memoir, one that concentrates on the vulnerability and suffering of the survivor. She does describe the intense pain of the injury, however, in the objective, almost detached manner required of a scientist. She has a relationship with her hand as an object of concentrated study. Her hand hurt terribly after the accident, but to her it was also an object of powerful fascination. She approached her recovery believing that curiosity is integral to her personal physical therapy, providing an antidote to fear. As an anesthesiologist explained, “It is difficult to reliably influence what we don’t understand.”

Her background in healthcare comes into play in this very personalscience narrative, which recounts an intense, obsessive curiosity about the structure and function of the hand, its myriad uses and its responses to pain. She learns quite a bit about a relatively small part of her anatomy that has an outsized importance to her, and to all of us.

In his 1978 BBC series, “The Body in Question,” physician Jonathan Miller, who is also a director and actor, asks a pertinent question: “Why is it we know so little about so much?” When he asks people on the street to point to the location on their bodies of their vital organs, most can’t locate them, except for their hearts. Fogg’s journey perhaps answers Miller’s question. When the body works, we tend not to pay much attention to it. A physical trauma, however, can focus the mind beautifully. What matters is where we put our focus.

Throughout the memoir, Fogg leavens trauma with therapeutic humor. When she contemplates how much her future rests “literally in the hands of others,” she says to a friend:

“I’m going to start a foundation,” I proclaim, to chase off darker thoughts, “to help victims of toilet accidents around the world overcome their humiliation. I’ll call it . . . the Toilet Emergency Association. TEA!”

Jacob Riis described humor as “the saving sense.” It can save us from our negative, self-pitying selves. There is evident suffering here, but it doesn’t eclipse the message of extraordinary resilience, and the need to place our trust in others. We are social creatures that have evolved to survive trauma.

The memoir closes with a near-miraculous development. As her healing progresses, one day a friend asks, “What are you doing for fun?” Realizing in that moment that mere coping was not enough, Fogg decides to take Scottish fiddle lessons, despite her right-hand impairments. With time she learns to play, and keeps coming back to a tune, “A Happy Day in June.”

She says, “My fingers know the music now, so that when I play it, I mostly forget myself.” Fogg suggests that when we lose ourselves in curiosity, discovery and creativity, we can find and express the deepest part of ourselves, a spirit that is ever so curable.—Tony Errichetti

Tony Errichetti is a CPA graduate from Columbia's Narrative Medicine program and co-founder of the Simulationist Narrative Medicine Community for individuals working in the human patient simulation field. His artwork titled “My Mother’s MRI: Brain-Mind Dataset” appeared in the Spring 2022 Intima. Find more of his work on IG: @thisdangerousmoment.