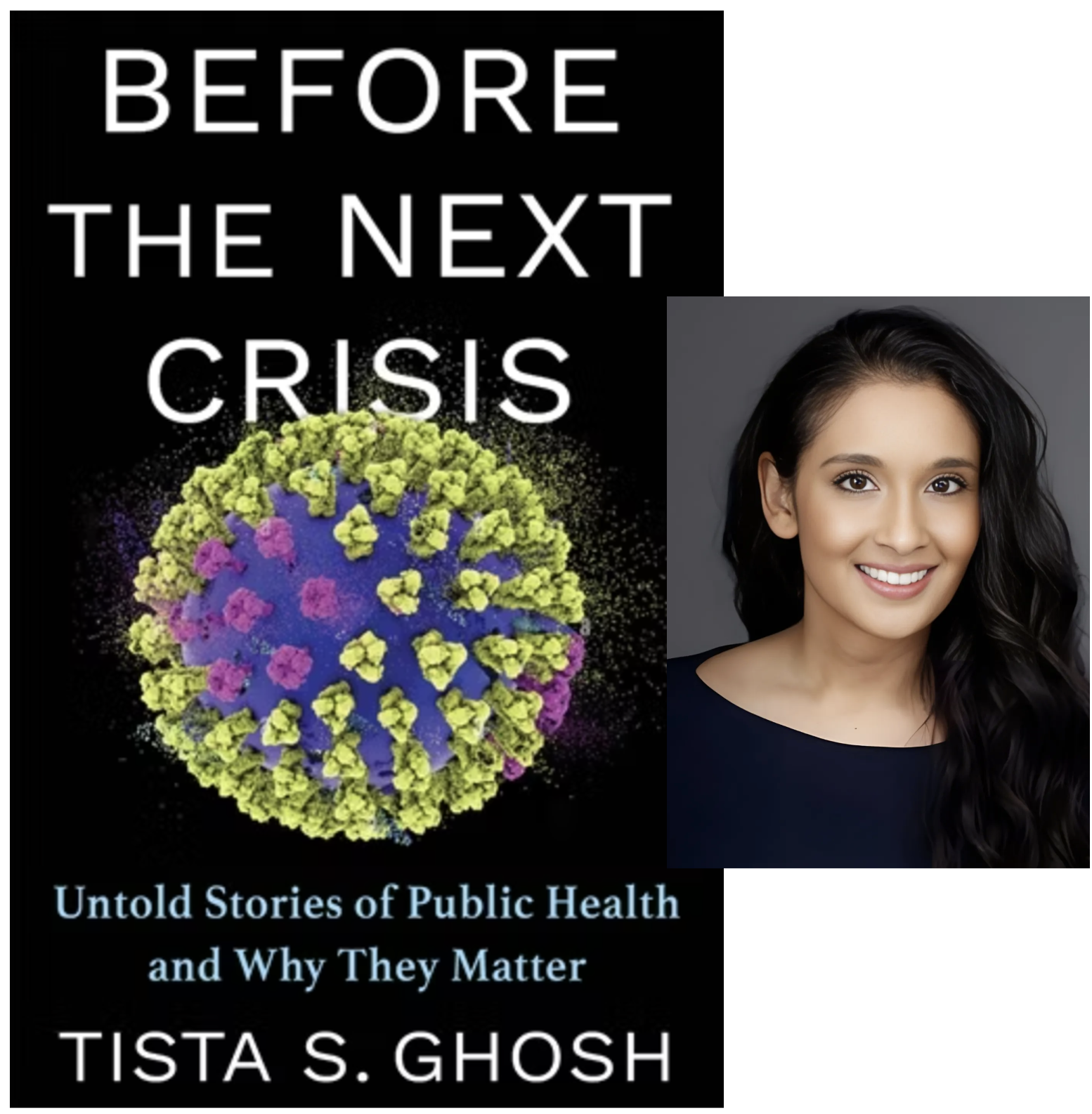

Before the Next Crisis: Untold Stories of Public Health and Why They Matter is Tista S. Ghosh’s urgent wake-up call to a country already drifting into pandemic amnesia. Drawing on her experience as a CDC-trained epidemiologist, chief medical officer for the state of Colorado, and health journalist, Ghosh examines the U.S. response.

Read moreThe Sky Was Falling: A Young Surgeon’s Story of Bravery, Survival and Hope by Cornelia Griggs

The sky is falling. I'm not afraid to say it. A few weeks from now, you may call me an alarmist, and I can live with that. Actually, I will keel over with happiness if I'm proven wrong," wrote Dr. Cornelia Griggs in her March 19, 2020, OpEd in The New York Times. Dr. Claire Unis reviews this reflective memoir.

Read moreOur Long Marvelous Dying by Anna DeForest

One moment of Anna DeForest’s Our Long Marvelous Dying, just published by Little, Brown and Company, captures the immense grief at the root of their new novel:

In the interval between giving a dose of intravenous opioids and seeing the peak effect, I will sometimes pass the time by catching up on the news. There is almost always a disaster imminent…You get used to it…

A sense of resignation and detachment pervades the story told by an unnamed narrator, who works as a palliative-care fellow in New York City after the peak of the early COVID-19 pandemic. In the first chapters, she recounts aspects of her training as a specialist, who “serves as a sort of illness interpreter, bringing the jargon of clinical medicine into the life and language of the patient who is living the experience.” It’s a specialty also “trained to be comfortable with [prescribing] the stronger stuff: morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl.” As the fellow learns these skills, an assessment of how her specialty serves the dying patient and her colleagues becomes clear:

The trouble that the other doctors have is not a lack of gentleness. Well, not only that. More often what they cannot do is tell the truth. They pack death up in so much misdirection, talk about the success or failure rate of this or that procedure or treatment, when the truth is the patient will be dead soon no matter what we come up with to do in the interim. That’s the part they need a specialist to say.

We also get glimpses of the narrator’s personal life: her relationship with her husband Eli, the dark ground-floor apartment they rent, the chess games she plays with her young niece Sarah, who her brother has left with them. We learn about the death of her father. Throughout the novel, the narrator seeks ways to withstand suffering—the global and local, present and past—in her daily existence.

Anna DeForest (they/their) is the author of the novels A History of Present Illness and Our Long Marvelous Dying, and a palliative care physician in New York City.

Photo by Stephen Douglas

Our Long Marvelous Dying is DeForest’s second novel and in some ways narratively follows A History of Present Illness, published in 2022, which challenged the lore of medical education through the story of a student managing her own personal trauma and the wider trauma of American healthcare. Reviews of DeForest’s first novel linked the writer, who works as a palliative care physician at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, to the narrator—and the same might apply to Our Long Marvelous Dying, as many moments seem pulled from the firsthand experience of a physician versed in hospice and palliative care.

In many of the novel’s settings, bereavement surrounds the narrator and often consumes her. But the grief that grounds the story and proves most unsettling for the narrator stems from the death of her absent and unkind father. DeForest structures the story to reflect the narrator’s apprehension towards him. We see him in pieces between scenes in the hospital, and can’t put him together as a whole until the very end. In managing the arrangements for his death, the narrator takes us through their fraught relationship. His favorite story to tell her romantic partners when meeting them for the first time is how whenever she cried as an infant, he said “I never liked you from the beginning.” But the cruelty of his abandonment is in its persistence—he is a “latent monster,” a “ghost” from whom she never stops craving acknowledgement.

Beyond her family, the narrator guides us through additional layers of grief in a way that we never stay long enough in one place to take up the devastation. The world offers constant tragedy—floods, destruction of coral reefs, extinction of thousands of species. And every day the COVID-19 pandemic rages. The reader hears about the refrigerated trucks lining New York City blocks, but what the reader sees in specific detail are the causalities for healthcare workers: their loneliness and coping mechanisms of alcohol use, disordered eating and SSRIs for suicidal ideation. During rounds, for example, an attending physician recounts the peak of the pandemic and says absently, “I am on an SSRI.” Meanwhile, the narrator notices the spring air coming through the window in his office that has “no bars, no screen. Fourteen floors up, with a view of the Empire State Building.” There is an omnipresent threat of self-harm, if not from one tragedy, then from the weight of so many others.

But Our Long Marvelous Dying is not a trauma dump. It confronts the obvious truths we train ourselves to overlook: the truth of death in a hospital, the truth of our own progression to death. It forces the question of “what is the purpose of living?” and does not give a satisfying answer. In this way, the novel’s title does not allude to the hidden deaths in the hospice wings, it alludes to us. Without despair, the narrator states “that all of us will die…that all of us are dead already.” The narrator acts as a palliative-care physician for us all, interpreting the jargon and euphemisms that drown the simple truth of daily tragedy. The sugar coating has dissolved, and she wants to communicate that “no one is coming to comfort you” and “nothing will help.”

One of the most provocative aspects of DeForest’s work is their ability to situate the reader in the day-to-day clinical world. The narrator normalizes death, dying and the grim collapse of human bodies that happens, not because of dispassion, but because of routine. While contributing to the book’s undercurrent of grief, the hospice unit provides meaning on a quotidian basis. On a phone call, in response to a mother’s dismay that her daughter may die before they arrive, the narrator reflects: “of course she can and does die alone.” In another situation, she reflects that an aging actress “dies the same as anyone.” These are tragedies that are contained, expected and managed.

Despite submission to muted sorrow, the narrator still attempts to manage her trauma. The palliative-care fellowship itself, in the view of its program director, draws those with personal layers of grief in addition to their professional interest. For the narrator, her work keeps the despair at bay and allows her to reflect on the minutiae of existence—for example, describing her underground commute as “the long stretch of track between where I live and everything that matters.” In revolving her life around the care of others, she does not have to generate her own will to continue living.

She also tries to endure by tempering her connections, especially to her husband Eli, a “well-adjusted” and handsome chaplain with a network of friends who adore him. The constant in their marriage is the restrained threat of its end, from “red flags” or laments that “it isn’t working.” This sense of detachment also manifests with her niece Sarah, who she describes as her “temporary daughter” while Sarah’s father is unable to care for her due to his substance use. We learn that an intergenerational dearth of attention and love has conditioned the narrator to the security of pain rather than love; the cycle of abuse contributes to her decision not to have children. The place where she seeks connection is a monastery out of the city, where she arrives and departs anonymous to her peers.

While there is no neat resolution, the protagonist steadily approaches the grief that eludes her—the death of her father. We see this through the lengthening of the scenes themselves. Initially, we learn about her father in brief moments between scenes of her palliative-care fellowship; by the end, we are allowed to linger as she sorts through his belongings. For a person who asks uncomfortable questions (Are you happy?) and speaks revolutionary words in a hospital (death and dying), the narrator takes her time to confront his death. She asks a rabbi at the hospital what to do after death about the bad acts her father committed in his life. Just as she can cut through medical euphemisms and jargon, he cuts through her question: “The weight you feel, he says, is not a need to forgive anyone. Just call it grief. Call it trauma.”

In Our Long Marvelous Dying, DeForest challenges our discomfort with death and instead leads with loss and our search for meaning within it.—Margo Peyton

Margo A. Peyton is a resident physician in neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital. Prior to medical school at Johns Hopkins, she worked in film and television story development for DreamWorks Animation. Her essays and book reviews have appeared in The New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA and the Boston Society of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry.

Black Death at the Golden Gate: The Race to Save America from the Bubonic Plague by Steven K. Randall

Black Death at the Golden Gate by David K. Randall

As life begins to resume a sense of normalcy, it’s important to reflect upon the lessons learned from the pandemic. Numerous parallels may be drawn to the bubonic plague outbreak of San Francisco at the start of the 20th century. Black Death at the Golden Gate by David K. Randall provides an account of the efforts led by public health officials to combat this disease. Randall is a senior reporter at Reuters who drew upon a wide array of sources, including telegrams and contemporary newspapers, to construct a narrative of the plague. Each chapter provides thorough illustrations of the physicians, scientists, and patients involved, to further draw the reader into the immediacy of the events.

Read moreThe Doctor’s Dilemma by Daly Walker MD

The Doctor’s Dilemma by Daly Walker

In his new compilation of 16 short stories titled The Doctor’s Dilemma, Dr. Daly Walker provides a stark portrait of physicians facing their own and their patients’ mortality, as well as navigating the practical morality of medicine —striving to do “right” in complex circumstances. As a retired general surgeon and accomplished writer, Dr. Walker melds intimate knowledge of medicine and particularly the surgical theater with a profound insight into aging, intimacy and loss. His archetypal character is an aging surgeon facing degradation of skill and encroaching self-doubt—changes that bring a sense of insecurity, a questioning of identity and a loss of control. His protagonists project outward strength and heroic intent, but struggle to find grounding in fraught relationships and their identity as physicians. This noble effort—to be present and perfect for one’s patients and loved ones, while reckoning with one’s fallibility and insecurities—is familiar to any physician. But that inclination is also highly relatable to general readers coping with the demands of daily life.

Dr. Walker writes what he knows in vivid, engrossing detail. Most stories are set in small-town Indiana, where he was raised and worked for decades as a surgeon. A Midwestern sensibility permeates his work in the jocular traditionalism of the surgeons we meet and in the dignity and modesty of other small-town characters. Dr. Walker brings further autobiographical elements; his characters are often veterans of wartime surgery with wisdom and relationships borne from intense, chaotic environments.

The Doctor’s Dilemma is divided in three sections: Mortality, Morality and Immortality, though these themes are often intertwined. A group of stories present aging surgeons losing skill and confidence, or on the other side of that deterioration. In “One Day in the Life of Dr. Ivan Jones,” we feel the confusion and disorientation of a retired neurosurgeon with dementia, as well as his physician son’s grief and struggle with his father’s loss of self. In “Old Dogs,” an aging surgeon has shaky hands and battles through a difficult aneurysm repair with scrutiny from an audience in the OR. We are asked to consider the value of life as absolute or relative— for a hemorrhaging Jehovah’s Witness patient where transfusion might negate an eternal afterlife; for a death row inmate needing intubation in the setting of scarce resources in a pandemic ridden emergency room. In “India’s Passage,” there is a gripping account of a young woman’s death during a routine laparoscopic surgery, and the oppressive guilt felt by the surgeon as well as the extreme grief and judgment of the woman’s mother. Ultimately there is reconciliation, but no character emerges unchanged from this tragedy.

Daly Walker MD is retired from a general surgery practice in Indiana. He is a graduate of Indiana University Medical school and served his residency at the University of Wisconsin. He served as a battalion surgeon in the Vietnam War. A fiction writer, his stories have appeared in numerous literary publication including The Atlantic. “Resuscitation,” one of the stories in The Doctor’s Dilemma, appeared in the FALL 2020 Intima.

Author photo: Sally Carpenter

Stories also focus on morality with physicians trying to do the “right” thing for their patients and their loved ones and neighbors. In “Drumlins,” an older surgeon physically marred by skin cancer surgery compassionately treats a young woman losing her breast from cancer. In “Jacob’s Ladder,” a retired orthopedic surgeon who lives a solitary life in the woods, having lost his wife, pines for the companionship of a young woman and ultimately saves her from an abusive partner and her son from the consequences of retribution. The idea of responsibilities of son and father comes out in several stories: In “Crystal Apple,” a physician who recently lost his mother is startled by the discovery that his father is not who he thought and grapples with his origins. In “Nui ba Den,” a surgeon reconvenes with a lover from his time in Vietnam decades later, and contemplates how the past influenced him and how his present self views the past. Mortality and morality are intertwined in “Blood,” where a mother adamantly refused blood transfusion for her critically ill Jehovah’s Witness son who is a minor; in “Pascals Law” where a physician intubates a man on death row; and in “Resuscitation” (first published in the Fall 2020 Intima) where a man stricken by Covid is intubated though other patients may have a greater likelihood of survival.

There is an immediacy to Dr. Daly’s imagery and language; his prose style is straightforward and deceptively simple in light of the issues he addresses, as this passage about a doctor’s thoughts after a challenging day at the hospital from “Resuscitation” demonstrates:

On his way home, Slater drove through the rain. The silent, empty streets and unlit shops conveyed an aura of apocalypse. The drops that splattered his windshield reminded him of contaminated droplets spewing from Mr. Bertini’s lungs. The car’s wipers slapped side to side. Slater had read Camus’ The Plague, and he felt like Dr. Rieux traveling through his plague-stricken city, finding it hard to believe that pestilence had crashed down on its people. He came to Shoofly, a chic bar and restaurant. Through a water-speckled window, he could see young people laughing and drinking, crowded together without masks. Their gaiety and disregard for the virus angered Slater. Don’t they care about others? He blamed them for him not being able to hug his children or sleep with his wife. He blamed them for Mr. Bertini’s illness. He wished they could see his patient and know what fighting for your life is like.

A Doctor’s Dilemma brings fresh insight and reflection to enduring themes of medical and surgical care—how to be human and have immense responsibility for one’s patients; how to balance the personal and professional knowing that perfection is impossible; and how to forgive oneself for that imperfection knowing that good intentions and hard work may need to be sufficient.— Eli Hyams MD

Elias Hyams MD is an adjunct associate professor of urology and a robotic surgeon at The Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University in Providence, RI. He has previously served on the faculties of Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine and Columbia University School of Medicine. He completed his undergraduate studies at Yale and is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. His residency at New York University-Langone Medical Center was followed by a fellowship at John’s Hopkins. His academic interest lie diagnosis and treatment of cancer of the prostate.

Carte Blanche: The Erosion of Medical Consent by Harriet A. Washington

“Urgent, alarming, riveting, and essential, Carte Blanche reveals that Americans, including African Americans, are still being medically experimented upon without their consent—yet again in research sanctioned by law. Harriet Washington’s powerful indictment of ongoing medical coercion unveils a gross violation of our human rights,” says Ibram X. Kendi. “It is vital reading at a moment when change is so necessary.” Carte Blanche: The Erosion of Medical Consent is published by Columbia Global Reports, an imprint that’s producing four to six novella-length works of journalism and analysis a year, each on a different under-reported story in the world.

Carte Blanche is a wake-up call to the many times researchers have skirted laws about informed consent and jeopardized a participant’s right to know. Washington has a laser-focus ability to make sense of complex statistics, target obfuscating data, put in context historical records and truly empathize with the accounts of those who have experienced what she calls “investigative servitude”—harm from the deterioration of informed consent, an important human right. Editors of the Intima spoke with her about how this groundbreaking exposé has an even more heightened importance during this challenging decade.

Read more