The death of a parent takes us into alien territory, a cold, silvery place we never could have imagined and a pain we never quite forget. As children, we revere our mothers and fathers; as teenagers, we loathe them, and it is only when one grows up, or becomes a parent, or goes through therapy, that a begrudging appreciation begins to form. Parents are truly the unknowable ‘other’ and the death of them startles the child in us, so much so that the adult in us is lost, with only a bewildering map of grief-behavior offered by outstretched, mostly sympathetic hands. Inevitably, we feel as if much has been left unsaid. “Some apologies are unspeakable. Like the one we owe our parents,” says poet Eula Biss in the essay “All Apologies” in Notes From No Man’s Land.

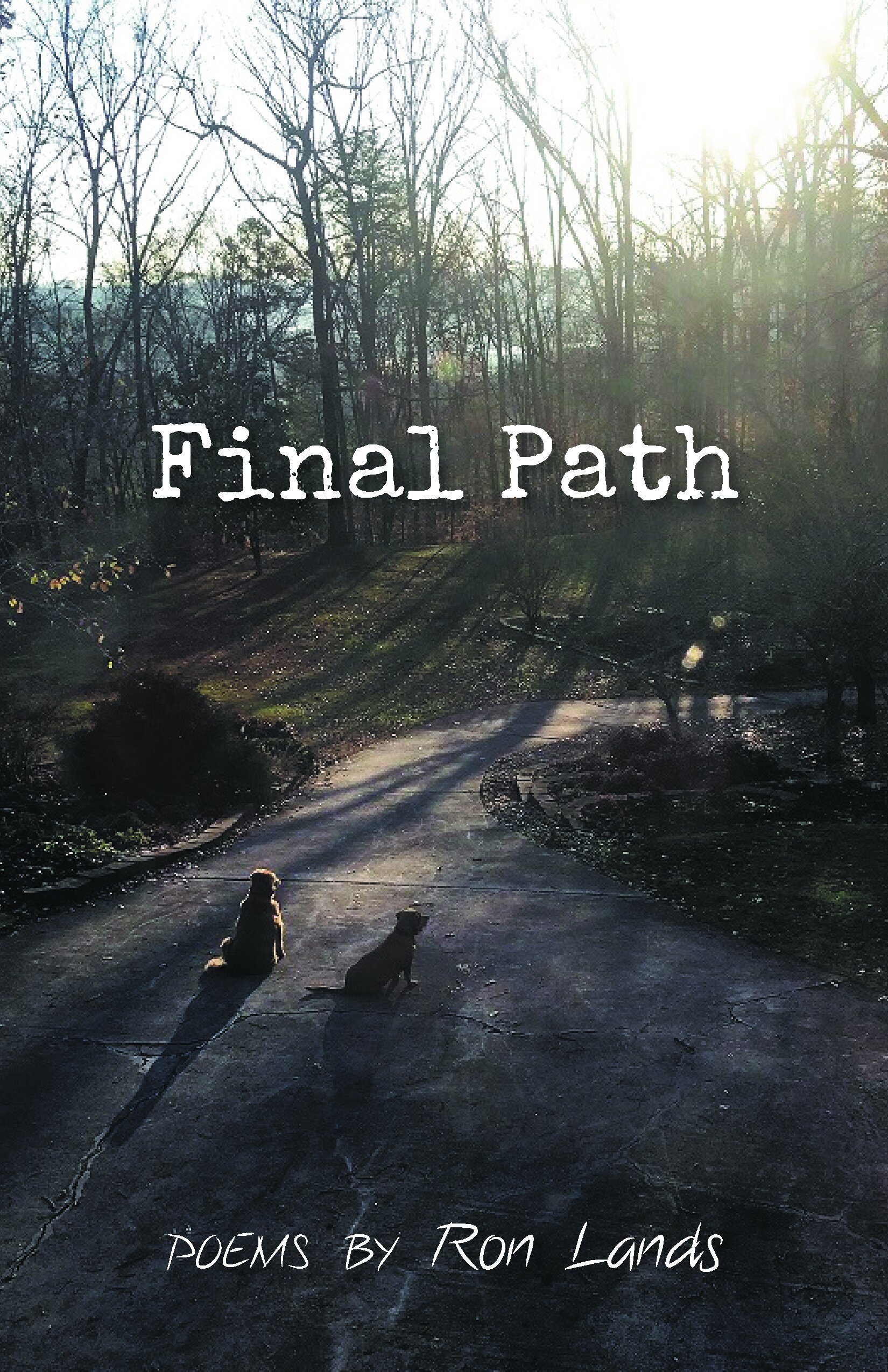

Early on in this bewildering year, a book titled Final Path by Ronald H. Lands, MD, came out, addressing that awful tangle of emotions tied up in feelings of loss, be it a parent, a friend or the over half a million now dead from COVID-19. Dr. Lands, a clinical professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, practices and teaches hematology. His book, he tells us in the Foreword, was “written in response to emotions and behaviors I recognized in myself as those I’d seen in patients and their families, people I thought I’d helped in their passage along their parent’s final path.”

Ron Lands is a semi-retired hematologist at UT Medical Center, Knoxville, Tennessee and an MFA alumnus of Queens University of Charlotte. He practiced medicine for many years near the community in East Tennessee where he grew up and was privileged to treat strangers, lifelong friends and a few relatives. His writing is about those experiences. His poem “Decision” was in Spring 2019 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine; “The Appointment” was in the Spring 2015 issue.

His beautifully-crafted poems are indeed responses to witnessing the pain, humiliation, fury and odd intimacy of watching a loved one die, and many allow the reader to exit the chaos of the present and move into a space of stillness and reflection, where life can irrevocably change. In “Now and Then,” for example, a memory of a story about a cutaway oak tree teetering “one way and then/the other, indecisive, not yet committed” captures the awe of a frozen moment when “the world went/silent, as if God had hit a pause button.” In the poem, that memory is triggered when his ailing father totters backward at the top of the stairs and his son grabs and catches him by the sleeve before he falls. It’s a flashback packing a lot of feeling in a few simple lines, one revealing the emotional ambivalence of watching a parent falter when ill.

There is often a larger-than-life quality we project onto the lives of our parents, and in some respect, that’s true here, although many poems in the collection show Dr. Land’s father after he’s been felled by respiratory failure. Initially, we get to know him in poems that feel like faded snapshots. In “Stealing Home,” we “see him on the front page/of the Times, August 9, 1948” a member of the Tennessee State Champs, “still skinny from the war, cap off center/cigarette dangling from a firing squad smile” (a foreshadowing of his death). The most affecting poems, though, are the ones where we see a son weathering the difficult moments alongside a dying parent in “The Conversation,” “Baby Steps” and “Listen to the Ocean.” We watch as Dr. Lands realizes he will be left to “breathe alone” when his father dies. He has learned to be attentive to the epiphanies that come at 3am or when “respirations slow;” we hear the doctor (and the man-child) exhaling in these lines that have weight and meaning then quickly flicker away.

Self-awareness also comes to this longtime clinician, who recognizes the pat phrases “I’d mindlessly repeated to the families of my dying patients for years” (Foreword), and it emerges in poems like “Don’t Tell Me What My Daddy Wants” and “It’s Not the Dying.” Genuine anger and frustration surface, and it is in the difficult rage of witnessing we experience the choke hold our healthcare narratives have on how people die:

It’s not the dyingIt’s the beatific looks of pity as doctors ration five minutes

for a comprehensive review of his complex problems.

It’s the double speak of a profession who bemoan a putrid,

Paretic, pitiful desire to help, if only they could escape the cold

Unfeeling shackles of managed care and restricted formularies…

… It’s the insouciant, self-satisfied surgeon who counsels

a dying man on the consequences of addiction.

It’s the absence of anyone who will believe

that when he says he hurts,

he is truly in pain.

What makes this collection sing is its sometimes biting sense of humor and concrete imagery. There is an emotional range in the telling of these tales of illness, death and dying, and Dr. Lands creates a comforting space that allows us to be open to the telling. It is because of its descriptions of the moments, of real, not imagined pain that we as readers feel a strong sense of relief in later poems capturing the “Letting Go” and “A Promise of Rest” emerging when “Darkness soaks your room.” The poem “The Language of Grief” inspired by poet Amy Hempel, has a funny ending, where we are told that sympathy is best when served in silence and being present, rather than pat phrases:

Learn from my dog, the one

who perfected the empathic presence

with a wet nose, a wagging tail and silence,

one who is fluent in the language of grief.

In the end, what we are left with when a parent dies are the quiet memories described in “Family Plot,” the last poem in Final Path. After the funeral and the acts of kindness, there is a sense of recognition in the moments Dr. Land explores alone, which feel less like an ending, though not exactly a beginning either. Here, the practical nature of being a doctor keeps this skillful poet physician from sentimental flights of feeling, and instead grounds him in the moment, as he will sit “with those scarred headstones/and listen for the call of songbirds/a gentle wind on dry branches,/the slap of broad drops on flat leaves,/echoes of mercy, whispers of love.”

Certainly, there is love that has been unearthed in the final path, and the moment recalls the revelatory way Mary Oliver calls upon Nature to center us in dark moments, as in her “Little Owl Who Lives in the Orchard,” his wings “a flurry of palpitations/as cold as sleet/rackets across the marshlands/of my heart,/like a wild spring day.” In Final Path, Dr. Land opens the door to a House of Light (the name of Oliver’s 1990 collection, where “Little Owl” appears), and he lets us enter and join him.—Donna Bulseco

Donna Bulseco, MA, MS, is a graduate of the Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University. After getting her BA at UCLA in creative writing and American poetry, the L.A. native studied English literature at Brown University for a Master's degree, then moved to New York City. She has been an editor and journalist for the past 25 years at publications such as the Wall Street Journal, Women's Wear Daily, W, and InStyle, and has written articles for Health, More and The New York Times. She is Editor of Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.

This review is dedicated to my friend Susan’s father Joseph Sarao, who recently passed away, and to my father Fred, who I miss every day.