Andrew Leland. Photo by Gregory Halpern

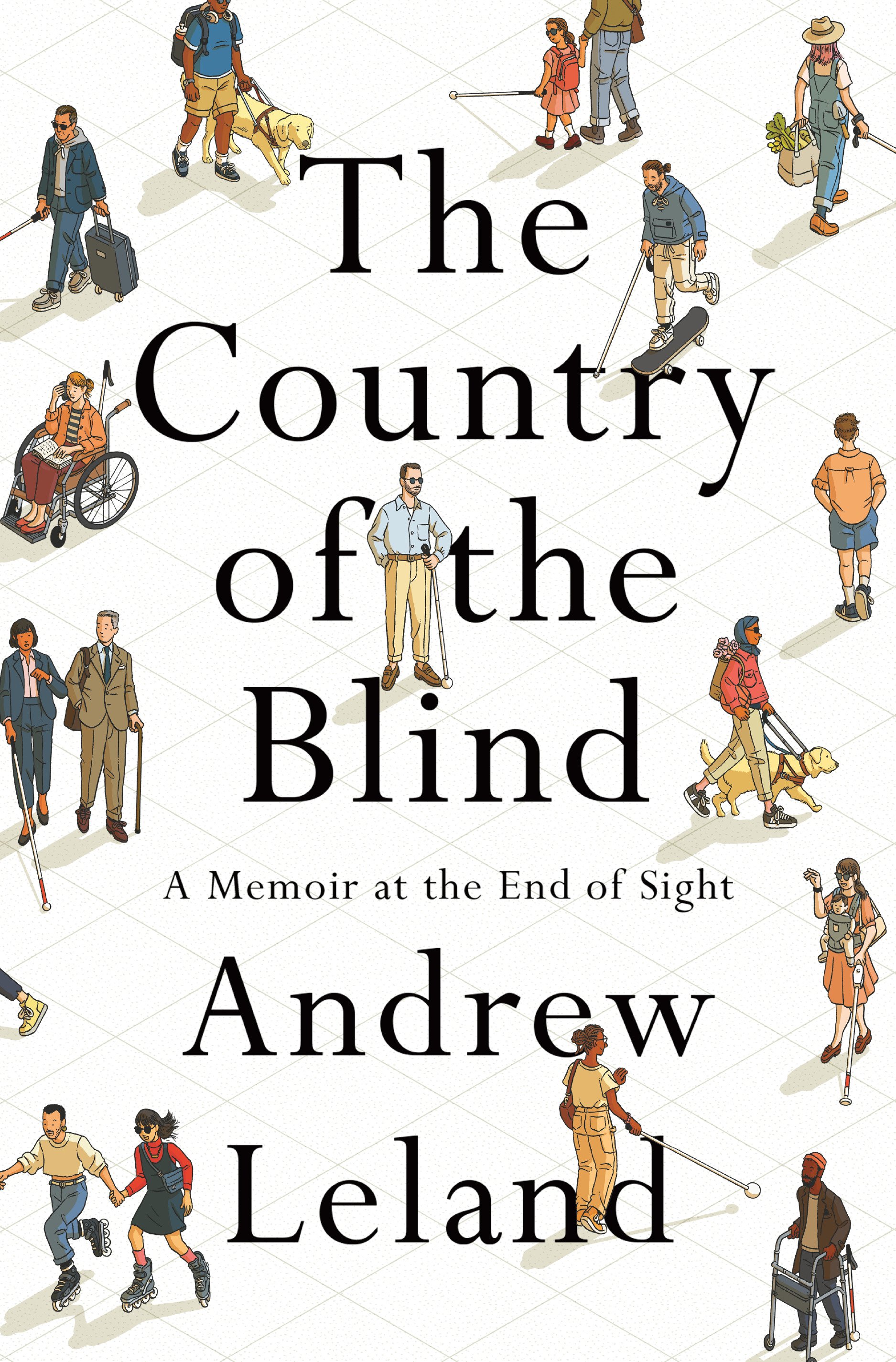

Doctors diagnosed Andrew Leland with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) when he was a teenager after he began struggling with night vision. RP is a degenerative disease that leads most of those who suffer from it to ultimately lose their vision, though that loss happens over years or decades. In knowing the rough future of his vision, Leland, a writer, audio producer, editor and teacher living in Western Massachusetts, sets out to explore what life as a blind person is before he actually arrives in the titular ‘country of the blind.’ That trip, which he recounts in “The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight” (Penguin Press, 2023), is more complicated than he originally envisioned.

Leland digs into what people mean when they use the word “blind,” as there are medical definitions, in addition to legal uses of the term, as well as social constructs and expectations. The medical definition is complicated, as only 15% of people who are blind actually have no vision at all. Instead, they have some sort of substantial hindrance to full sight, but those issues vary wildly. In fact, most of the people in the book are more like Leland, people with some partial sight, even if that is nothing more than distinguishing light and dark patches of the world.

The legal aspect of the term leads to who receives benefits and who doesn’t, which gets into a question of privilege. Somebody who is unaware of the legal definition of blindness wouldn’t fill out appropriate paperwork and then wouldn’t be eligible to access the considerable number of resources available for those who are legally blind. Similarly, if somebody has 1% of their vision loss from being legally blind, they are not qualified for those benefits. As with all legal definitions, the line is arbitrary, but there is a legal need for that line. After all, vision has “the privileged place it holds at the top of the hierarchy of the senses.”

One of the most complicated parts of the term “blind” comes from the social construct of that term. Given that most sighted people define the term “blind” to mean that the person has no sight at all, Leland struggles to see himself as blind (and note how encoded vision is in our language, with terms like ‘see’ or even ‘self-perception’). One scene in particular that highlights this issue is early in his use of a cane for mobility. Leland talks about how he’s still able to read, but navigation, especially in darker places, such as restaurants, is a challenge, so he begins using a cane.

At one point, though, he and a man on the street catch one another’s eyes, and that man can tell Leland sees him. He mutters words to the effect that Leland isn’t blind, that he’s pretending on some level, which causes Leland to question whether he can truly refer to himself as blind.

Leland uses his doctor’s definition of his deteriorating sight to expand on that question of definition: “Slow, subtle, and present is such a strange way to experience a phenomenon like blindness. It’s so much easier to conceive of it as a binary—you’re either blind or you’re not; you see or you don’t.” Leland’s book questions that idea of binaries throughout.

Throughout Leland’s journey to explore the country of the blind, he goes to conventions where almost all of the attendees are blind, where he finds a world built around their capabilities, not one where they have to adjust to the capabilities of sighted people who make the rules and the society. He also finds conflict between groups who disagree on how best to advocate for a world where those who struggle with vision can function at the level of their abilities. This divide is especially clear in the generational difference, as the older part of the community wants to push for rights for those who are blind, focusing solely on that issue.

Younger members, though, take a more intersectional approach, connecting vision to race, gender, sexuality, other disabilities, gender identity, and other issues of identity. Leland reminds readers that the Civil Rights Act doesn’t include disability as a legal protection, which helps lead to this divide, given that the older members are more focused on that aspect alone. That divide becomes much clearer in 2020, in the wake of the protests over the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among others. While the community doesn’t agree to broaden their focus, they at least begin to have more conversations around issues of identity that go beyond blindness.

One of the most interesting chapters is “The Makers,” where Leland explores the technology that often enables those who are blind to interact more fully in a world not designed for them. There are two ideas he explores that might surprise sighted readers. First, much of the technology that exists to enhance blind people’s abilities comes from the blind community themselves. Since society doesn’t fit with how they need to function, they piece together technology to help themselves function. For example, well before the internet and chat rooms, members of the blind community hacked into phone systems to provide open, free lines for conversations, including Joe Engressia, dubbed by The New York Times as “the Peter Pan of phone hackers,” who in the 1970s could perfectly mimic the tones of the phone systems to make free long-distance calls.

Second, much of the technology the blind community created—either on their own or working with private companies—ultimately became a part of the broader society: In the 1920s, 78 rpm records would play recorded books, but they only played three to five minutes per side; in 1923, after his appointment as director of research and education at the American Foundation for the Blind, Robert Irwin worked with an electrical engineer to design a record to play at 33 1/3 rpm, tripling the capacity for recorded books. Other members of the community helped develop technology that led to audiobooks and Auto-Tune, as well as the pulse oximeter (scanners doctors clip to patients’ fingers to measure pulse and oxygen levels); video-game light guns; optical character recognition, which ultimately led to searchable databases; QR code readers; and voices like those of Siri and Alexa.

Even the question of technology, though, leads back to the question of the definition of a term like disability, a social construct rather than an actual definition. Leland writes, “If you need a cane or a guide dog to safely cross the street, you’re disabled; if you need glasses and a pair of shoes to get you there, you’re fine. But the relationship with the tools is the same.”

Most of us rely on technology to function on a daily level, but those in power—in this case, those who have more use of their eyesight, even if they use glasses to do so—define what is and what isn’t a disability, and who is disabled and who isn’t. While those of us who have our sight might think we are able-bodied, we often overlook the technology we use to survive. Leland wants to remind readers of that to help them look at the world and those with what we refer to as disabilities differently. As he writes early in the book, “My hope is that this book will encourage the sighted reader to likewise discover the largely invisible terrain of blindness, as well as other ways of living and thinking they might not have previously considered.” Again, he wants us to see differently.

Ultimately, Leland has increasingly lost more of his sight by the end of The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight, and he’s having to come to grips with that loss. Rather than focusing on what he is unable to do, he shifts his attention to what he can do and all of life that he will continue to enjoy. Near the end of the book, he writes, “I also thought that this camaraderie suggested an alternative model of care, and of blindness...: A blind person who’s not broken, but who’s still vulnerable; blindness itself as at once a non-defining characteristic and a serious disability; and a path to rehabilitation that doesn’t mean accepting deprivations, but that still demands an acknowledgement of the pain that one must pass through to arrive at blindness’s full joy and humanity.”

Leland inhabits a liminal space, not merely because blindness isn’t a binary, but because he wants to remove the binaries that exist in and around the blind community. Blindness doesn’t define him, but it is an aspect he needs to acknowledge to live a full life. The final titled chapter is “Half Smiling,” where he realizes that people react differently to him if he has a half smile on his face as he walks around.

More importantly, though, it’s about his approach to the world. He’s not happy that he is losing his sight; he doesn’t romanticize the blind, an aspect he criticizes earlier in the work by looking at characters such as Tiresias or Oedipus. However, he’s happy that he has joy and humanity in his life, and he’s choosing to remember it, in spite of the complications his vision loss brings.—Kevin Brown

Kevin Brown (he/him) teaches high school English in Nashville. He has published three books of poetry: Liturgical Calendar: Poems (Wipf and Stock); A Lexicon of Lost Words (winner of the Violet Reed Haas Prize for Poetry, Snake Nation Press); and Exit Lines (Plain View Press). He also has a memoir, Another Way: Finding Faith, Then Finding It Again, and a book of scholarship, They Love to Tell the Stories: Five Contemporary Novelists Take on the Gospels. Find out more about him and his work on X-Twitter at @kevinbrownwrite or on kevinbrownwrites.com