Sentient is a celebration of sentience, specifically of humans. Primarily defined as one’s ability to experience the outside world, author Jackie Higgins uses various examples from the animal kingdom to lavish praise on this wonderful ability in humans compared to animals.

Peacock Mantis shrimp, for example, possess a highly developed sense of sight, being the only creatures able to grasp circularly polarized light. With no less than 12 different kinds of photoreceptors, their eyesight is much more developed compared to that of humans from an anatomical perspective. Most people are trichromats, having only three kinds of cones or receptors for color-vision: green, red and blue. A few special ones are tetrachromats, with an additional cone sensing shades between red and green. Physiologically however, human color vision was empirically found to be much more precise. ‘How is that possible?’ you might ask—it’s thanks to the highly developed human brain, capable of elaborating and integrating different external stimuli.

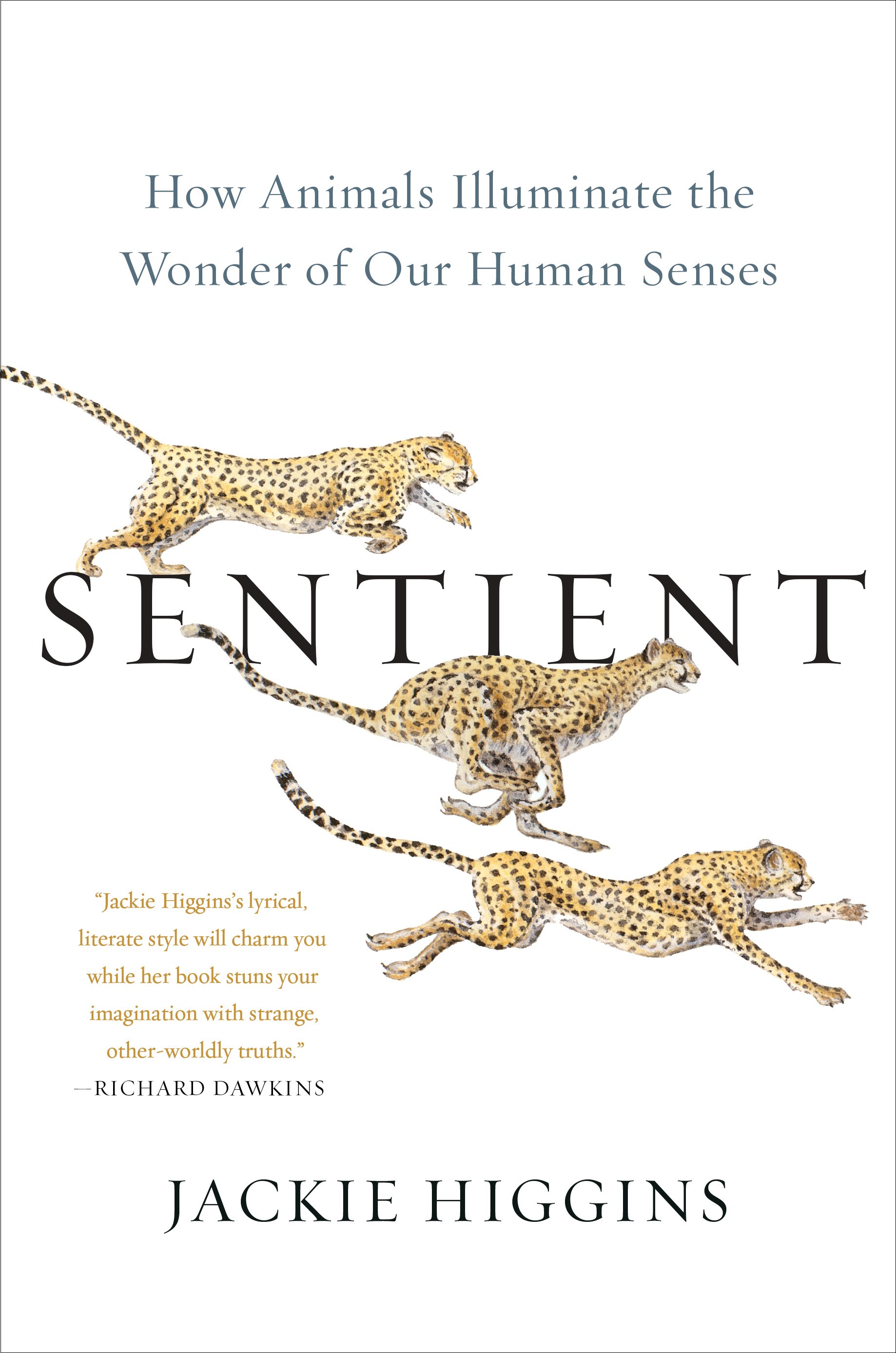

Throughout this fascinating book, Higgins, a graduate of Oxford University with an MA in zoology who has worked for Oxford Scientific Films for over a decade, displays her complex understanding of the non-human world. Moving on from the Peacock Mantis shrimp, she uses a litany of creatures to examine and worship the experiential world humans share or do not share with animals. We meet the spookfish and great gray owl; the star-nosed mole; the common vampire bat; the goliath catfish; the bloodhound; the giant peacock; the cheetah; the trashline orbweaver; the bar-tailed godwit; the common octopus; and the duck-billed platypus. With the platypus, for instance, we do not share the ability to sense electric fields.

We’re introduced to others engaged in (some might say ‘obsessed’) with these fascinating life forms. “‘My major research love in life is the mantis shrimp,’ confessed Justin Marshall, the professor in charge of the Sensory Neurobiology Group. He and his team are often seen swapping lab coats for snorkels and scuba gear to brave encounters with these plucky crustacea and keep their aquarium well stocked.” In some ways, Sentient is an informative and entertaining travelogue into worlds we’ll never visit, much like one of Sir David Attenborough’s documentaries (“A Life on Our Planet” or the most recent “Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet” come to mind). We are taken to the farthest reaches of the earth to meet and reflect upon the tiniest or most gigantic organisms mirroring the miracle of the world’s biodiversity and innate creativity.

As an author—and our guide to microscopic/macroscopic worlds—Higgins has an engaging prose style, educating us with her knowledge without boring us to death. Note her way of ‘teaching by showing,’ rather than simply ‘telling’ in this passage from a chapter about the bloodhound and our sense of smell:

Smell starts in dogs and humans when scent molecules are caught on an incoming tide of a breath, wash through to the depths of our nasal cavities, and reach the olfactory epithelium. This moist and mucous-coated membrane is crammed with olfactory neurons—the nose’s answer to the cones and rods of the eye, the hair cells of the ear, the mechanoreceptors or touch neurons of the skin, and the taste buds of the tongue. The business end of these long cells bears microscopic cilia that stick out and wave in the air current. These hairs are coated with olfactory receptor proteins that snare the passing scent molecules. The American neuroscientists Linda Buck and Richard Axel made the unanticipated and astonishing discovery—for which they were awarded the first ever Nobel Prize for olfaction in 2004—that mammals share an enormous family of genes that code for these receptor proteins. So the noses of dogs and humans are primed with the same kinds of scent-snagging biology.

Jackie Higgins

Photo by Alex Schneideman

Our ability as readers to be sentient certainly works to our advantage in gleaning the lessons that come from reading Sentient. Two important ones stood out to me: One is that evolution is a truly magnificent process, leaving one in awe in light of its intricacies and successes (as well as forgotten failures). In that regard, humans are no different from non-human animals in that we are all experiential creatures, treading life as we experience it and trying to survive and prosper.

The second lesson is in humility. Philosopher Thomas Nagel’s query of “What does it feel like to be a bat?” courses throughout the book, reminding us once again what Socrates tried to teach us centuries ago: We do not know what we do not know. We humans do not know the outer world we cannot experience. Technology helps a bit, for sure, but some parts of objective reality will forever remain uncharted territory for us, while being visible (or rather experienced) for others. Human abilities should then be praised without a doubt, but praise does not necessarily mean preferable, or more advanced, or superior. Humans and non-human animals alike have evolved to excel in their own habitat, made to respond to experiences sometimes only they are privy to.

So next time you feel like God has put you here to rule the animal kingdom, try to put yourself in the bloodhound’s paws—potentially there is a whole world out there that only he can experience.

Sigmund Freud reportedly thought that humans exchanged their sense of smell for superiority over animals. He was wrong. As with other senses, there is no ‘superior,’ only ‘different,’ and even that difference may be simply a matter of practice. As Higgins writes, “the dog beneath the skin exists within every one of us, waiting for our whistle.”

Sentient is a fun and illuminating read, highly recommended for those who cherish the winged or four-legged, or other creatures that walk, swim and fly among us. The book is even more highly recommended for those who don’t. —Zohar Lederman

Zohar Lederman is an emergency medicine resident at Rambam Healthcare Campus in Haifa, Israel. He received his PhD in bioethics from the National University of Singapore and was awarded a post-doc fellowship at the Medical Humanities and Bioethics Unit at the University of Hong Kong. His academic interests include narrative medicine, public health ethics, One Health ethics, and clinical ethics. Lederman was on the editorial board of Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine, overseeing the review of academic papers and the 2016 Intima Essay Contest, “Patients, Providers and Pets: One Health for All,” a call for stories reflecting zooeyia, a term coined to account for the salutary effect pets bestow on humans.