Being sick takes work. There is the pain and exhaustion, the adaptation, the cognitive load required to keep moving forward when my body holds me back. There’s also the business of being a patient: sitting in waiting rooms, standing in line at the pharmacy, being on hold with the insurance company.

Amanda Ford is a writer and scientist living in Northern California. She trained as an astrophysicist; her work on galaxy formation and evolution has appeared in Science, The Astrophysical Journal, and Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. She works as a data scientist for the San Francisco Mayor’s Office; using statistics, modeling, and analysis to improve the City’s response to the homelessness crisis. Ford, a survivor of cancer and brain injury, is learning how to live well with severe Lyme disease. Her essay, "Another Day of Childhood" appears in the Spring 2024 Intima.

The part I hate most is feeling like I have to be my own doctor, even though I have no medical training. For years, doctors have dismissed my symptoms, pronouncing me merely “stressed.” Unsatisfied, I have spent eons reading articles on PubMed, cross-referencing terms with anatomy books and medical glossaries, researching rare illnesses and doctors. It has amounted to nearly a full time job.

While I wish I could have used this time and energy in other ways — healing my body, living my life, parenting my son (or at least, as I discuss in “Another Day of Childhood,” not making him feel like he has to parent me) — I do understand why this self-doctoring happens.

I know there is and always will be sickness. I know our knowledge of the world, including all the malady and illness in it, are at best a work in progress. The anger I sometimes feel at the doctors, the systems . . . well, maybe that’s just how it is. We’re all imperfect. Perhaps I should just be an adult and move on.

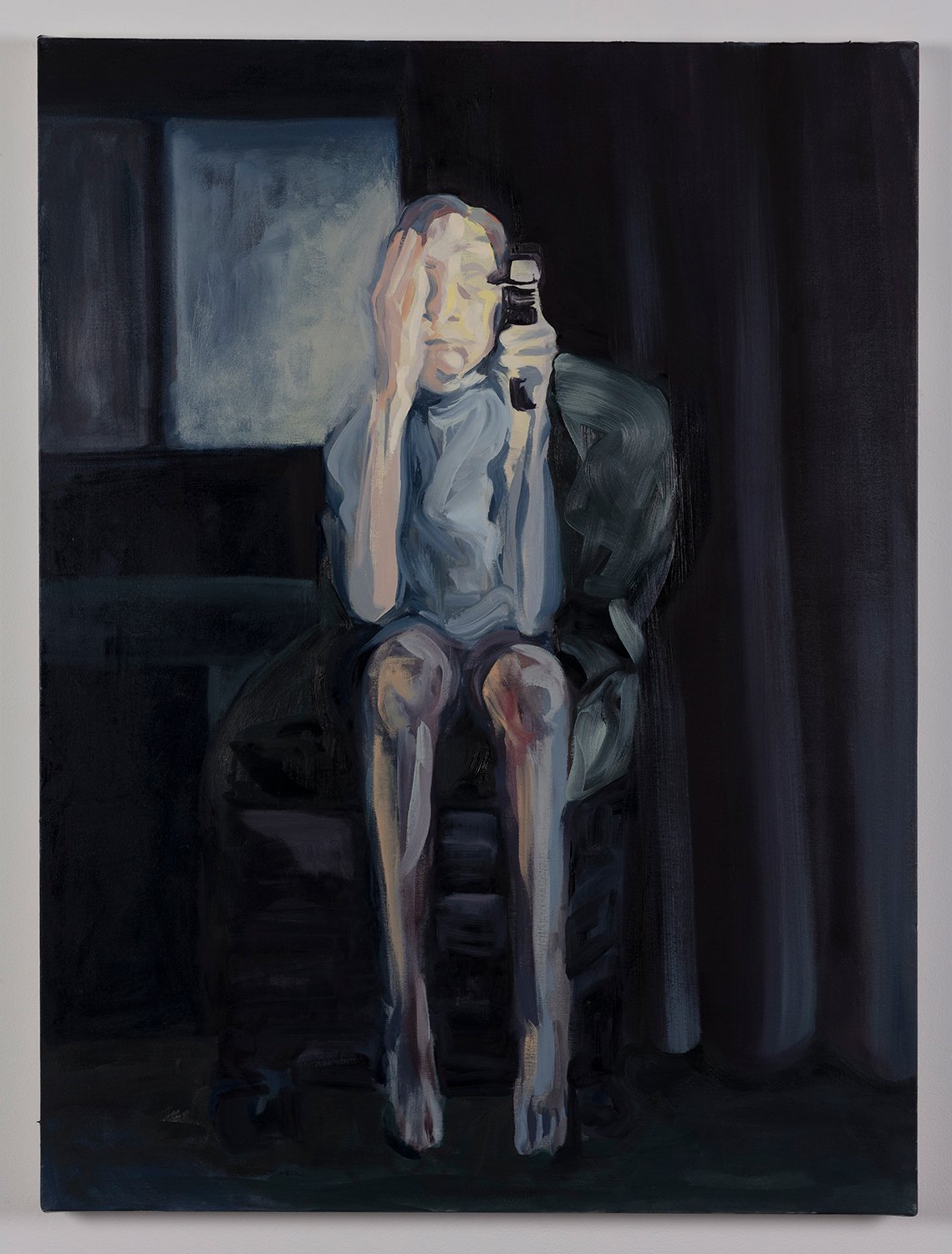

Self Examination with Otoscope by Abigail Parsons. Spring 2023 Intima

And yet, the suffering this self-doctoring causes me is intense. It is absolutely exhausting to do all this work, and terrifying to realize so much of my health is in my own sick, sore and vastly unqualified hands. Every time a doctor tells me it’s “up to me,” every time I’m supposed to research surgery options (!), every time I get a secure message on a patient portal with words the Mayo clinic website has to explain to me at length, I want to scream.

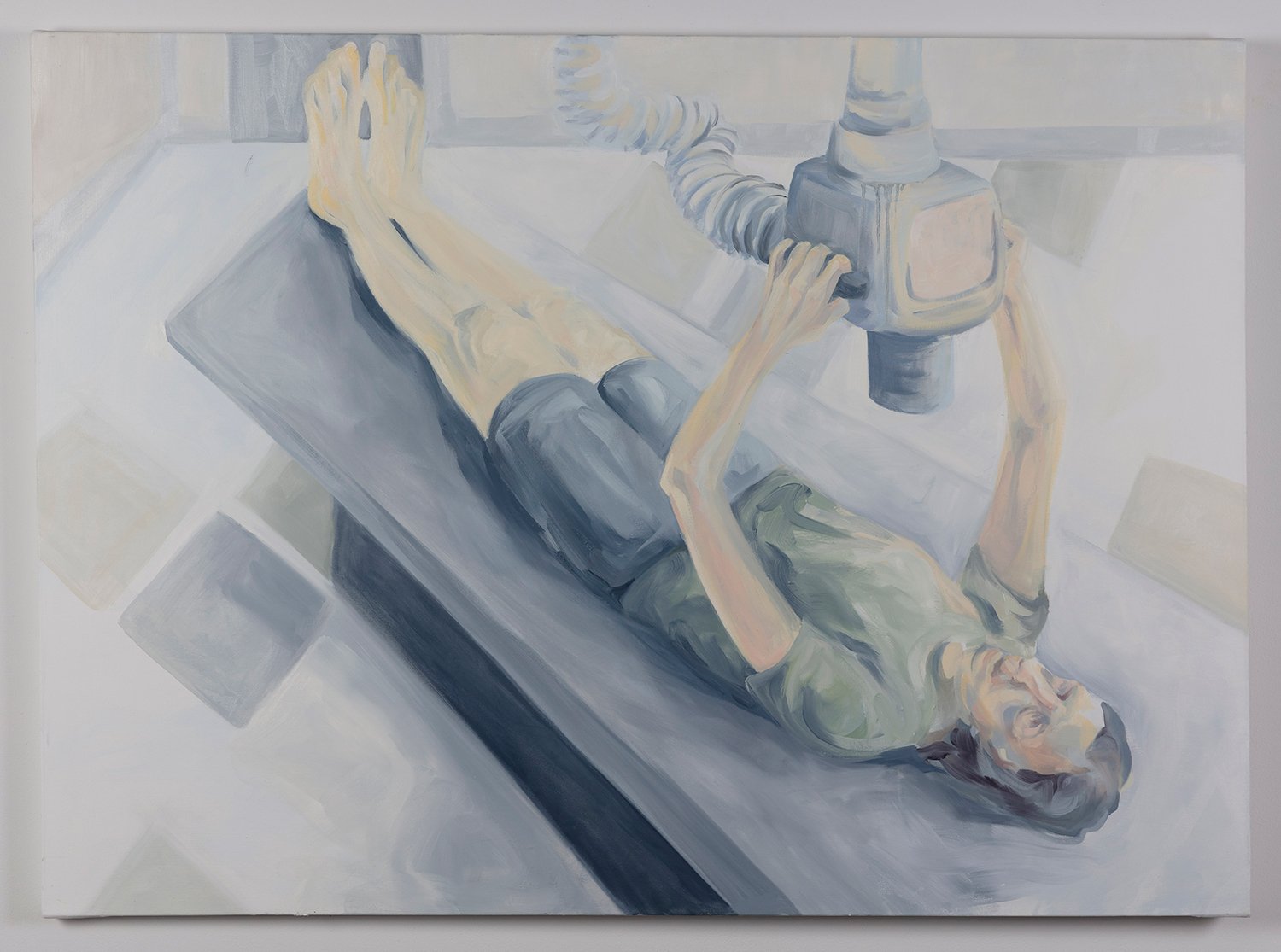

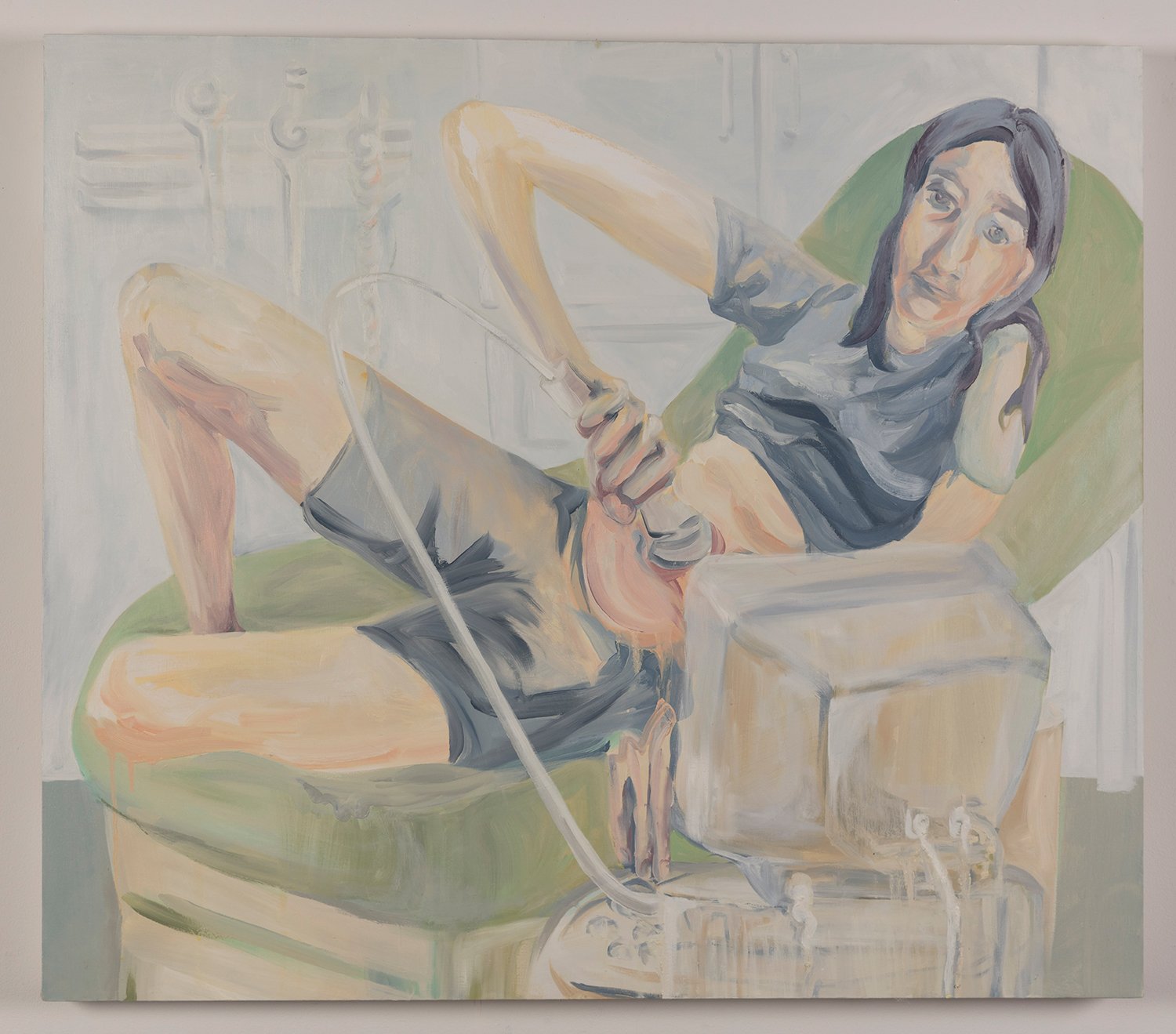

When I found Abigail Parsons’ trio “Self-Examinations,” I felt seen. Viewing her depictions of patients attempting to examine and diagnose themselves with awkward medical instruments, I felt like I was finally able to take a deep breath and relax my body.

Self Examination with X-ray by Abigail Parsons. Spring 2023 Intima

“Self-Examinations” doesn’t show us how to solve the problem. But with its vivid depictions of tired, deflated patients, it makes clear the absurdity of expecting sick people to take on this work. It shows the status quo to be untenable, and insists on a better way.—Amanda Ford

Self Examination with Ultrasound by Abigail Parsons. Spring 2023 Intima

Amanda Ford is a writer and scientist living in Northern California. She trained as an astrophysicist; her work on galaxy formation and evolution has appeared in Science, The Astrophysical Journal, and Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. She works as a data scientist for the San Francisco Mayor’s Office; using statistics, modeling, and analysis to improve the City’s response to the homelessness crisis. Ford, a survivor of cancer and brain injury, is learning how to live well with severe Lyme disease.