Kathryn Taylor is a community doctor who works at a homeless clinic in San Francisco, California. Her essay, “On My Way to Work: A Walk Through San Francisco’s Tenderloin District ,” which was nominated for a Pushcart Prize, appeared in the Fall 2023 Intima. Another essay: by Taylor: “Delusional Parisitosis, Delusional Me,” appeared in the Spring 2022 Intima.

I work at a community clinic with patients who are homeless–there is the stigma of homelessness, and then there is the stigma of looking homeless.

Some patients of mine do not–or do not yet– appear unhoused. It is usually those who still have family that support them, who live in a car, who hold a job—running food for Doordash, picking for Amazon, sitting security—or who have not been homeless for so very long. But many of my patients do appear frankly homeless: a shuffling gait, a blanket draped around their shoulders, belongings pushed in a stroller, blackened teeth, leg wounds.

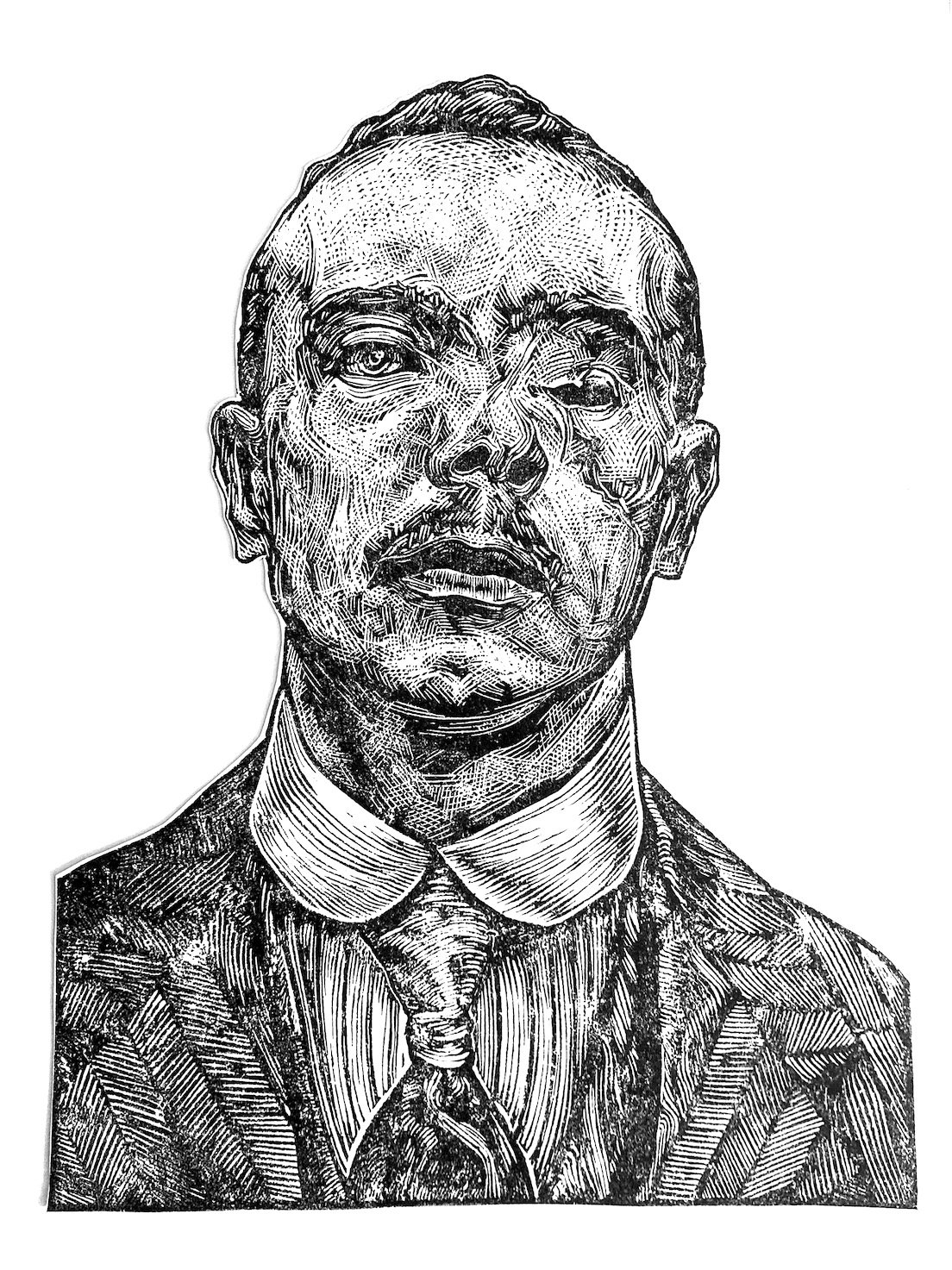

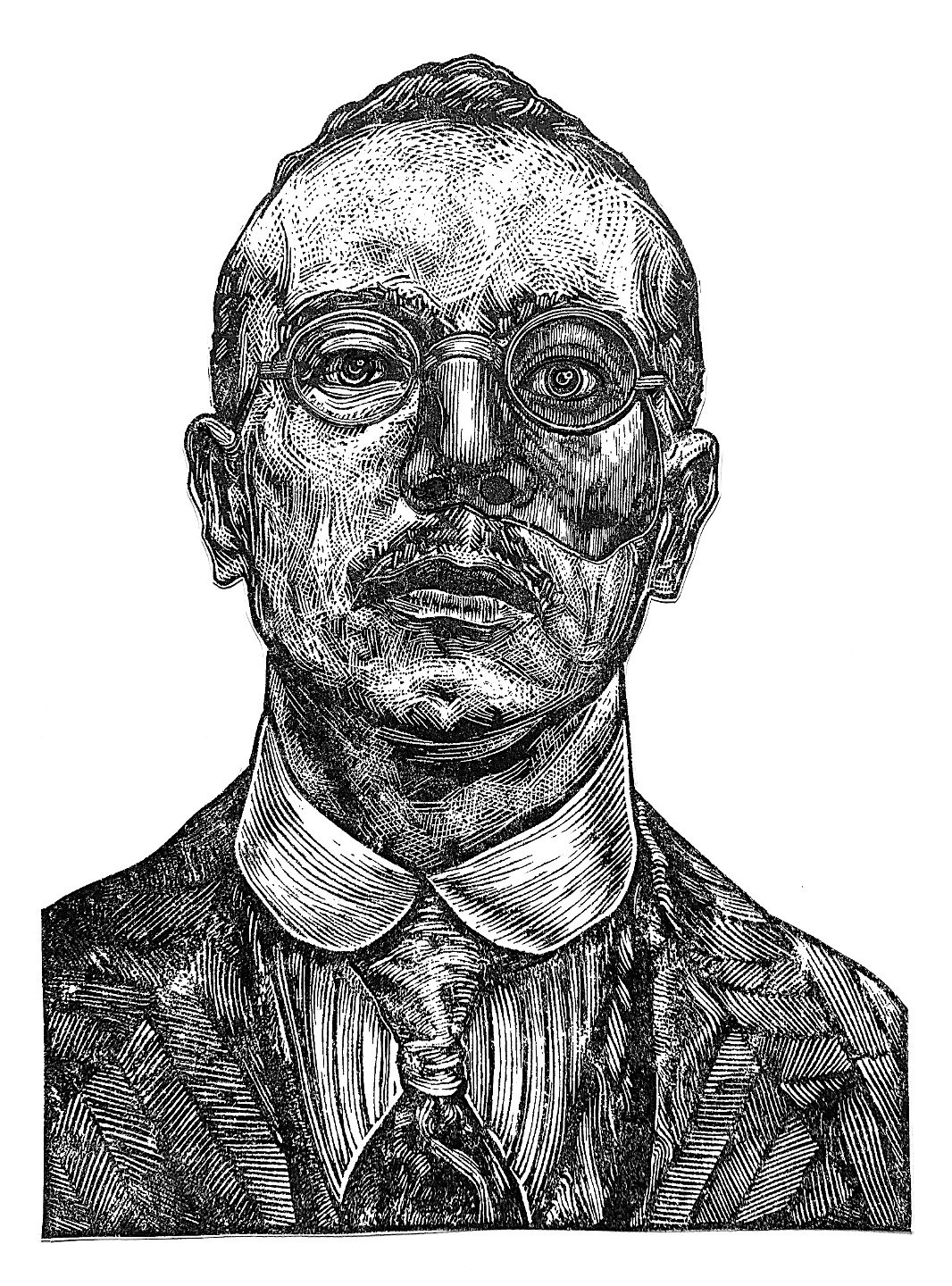

Nathan Makarewicz’s linoleum diptych “The Face as an Organ of Identity” (Spring 2023 Intima) shows a WWI veteran in suit and tie who is not wearing, and then is wearing, a metal prosthetic over his disfigured left eye, cheek and nose. In the first print, he is strikingly and easily identifiable as maimed, while in the second it takes a few moments to recognize something is unnatural. Not immediately, but soon, you note the different texture of the left cheek, asymmetry of the eyes, the edge of the metal prosthetic as it runs from his nose to his eyebrow, over to his ear, and down and across to his upper lip.

There is something inherently satisfying about seeing this diptych side by side. Like a plastic surgery ad, it shows you the benefits of a normalized face, of this prosthetic, of how improved a person can look. And in seeing that improvement, I am happy for the man, that his life gets to be bettered in such a clear and concrete way. And yet, there is great sadness in this side by side, too, that this man was called into a war that left his body so irrevocably disfigured. That countries send men to try to kill other men. That there is war at all. Really, in the larger timeline of this man’s life, the prosthetic print, the “after” is really more of an approximation of his “before,” when his face was not blown off, cut, stabbed, or whatever terrible thing befell this poor soldier. His scarred face is his forever after.

Sometimes, a patient will show me their before photo: what they looked like in high school, or before drugs, or when they were young or with their kids. And I am happy to see them in a better time, but it also is a moment full of sadness, that they are here, homeless, with me now. That society can’t figure out how to help those in the margins. That people are homeless at all. And I so wish for them to return to that life in the photo. I pray we can work together to return to an approximation of their before, before there is a new infection, a traumatic brain injury, an overdose. Sometimes we can. Because the longer they are on this battlefield, the harder it becomes to get out unscarred.

Kathryn Taylor is a community doctor who works at a homeless clinic in San Francisco, California.