Humans can create a world through perception, imagine a potential life, whether it be the life of a relationship or the life of a baby. We fill in the unknown details to make a whole that is pleasing and good. It’s as if we willfully ignore that so much of life is unpredictable.

Read moreA Simple Ritual: Reflecting on the Moments Before Surgery by poet and orthopedic surgeon Photine Liakos

Surgeons are well-known for precision and protocols. There is often a ritual nature to our actions when preparing for surgical interventions, an orderliness and discipline: checklists, time-outs, pauses, consensus.

Read moreWhen the “Clock of the Living” Runs Down: A Reflection by clinical social worker and chaplain Betty Morningstar

The fractured stories at the end of life often reflect an ineffable but powerful experience of creativity, insight or even revelation. These opportunities arise because the dying person doesn’t see time according to the clock of the living. Imagine how much one could conceive of were time not of the essence.

Read moreThe Shit Poems: A Reflection by Drea Burbank

I am interested in the juxtaposition between my use of poetry to shed traumatic experiences and memories from medicine, and the description of William Carlos Williams by Britta Gustavson (“Re-embodying Medicine: William Carlos Williams and the Ethics of Attention,” Spring 2020 Intima).

Read moreThe Limits of Love: A Reflection by Carmela McIntire about Anorexia, Overeating and Fulfillment

Disordered eating occupies a spectrum—anorexia nervosa at one end, morbid obesity at the other. Attempting rigid control of the body and its appetites, anorexics are unable to see themselves and their bodies accurately. Compulsive overeaters—often obese—similarly might not see themselves accurately. In both disorders, controlling food is the aim, a genuine addiction, a strategy through which addicts deal with the world and their own circumstances—a necessary coping skill, even though it is risky to health in both cases.

Read moreWhat I Learned about the ICU: A Reflection by Benjamin Rattray

In her essay “The Shape of the Shore” (Spring 2020 Intima), Rana Awdish takes us into the intensive care unit during the ravages of a pandemic. She shows us “…the desperate thrashing patients on the other side of the glass” and “…the sticky blood on the floor.” As I read the words, my breath becomes shallow as fear and grief pummel into me. Somewhere deep, beneath the shrouds of consciousness, the words resonate, and I feel as though I am slipping beneath an indigo sea.

Read moreEmpty Highways by Cole W. Williams

Last spring, I drove down empty highways, once frantic with traffic creating a decibel assault, turned strangely serene. Red-tailed hawks perched on light posts felt eerie without the usual commotion. I couldn’t help myself from imagining me gone too, all of us, and the hawk perched despite everything on this empty highway. “Little Isolated Bird” by Brent Carr, recalls the lonely feeling of my drive. The shadow image of a lone bird speaks to a palpable theme; isolation turned loneliness of our innermost desperation during the pandemic.

We have found ourselves in pockets of silence, instances of loneliness with no resolution and often sleep disturbances too. “Overnight Aubade” is a poem of isolated sleeplessness—as depicted in “Insomnia Dreams in the Moonlight” by K. Johnson Bowles—to me the heart is bandaged in the collage and razor blades float all around us in our dreams. However, the poem is also about the craving for connection; how we survive for it.

Most professions don’t require interfacing with daily tragedies and loss. My husband does not work in one of those fields. As an ICU physician, he often works while I sleep and as I lie awake wondering about the state of the pandemic, he is interfacing directly with it. The following mornings I will (maybe) hear stories of the struggle for life and the innate human tendency to resist loneliness.

In “We Almost Lost You” by Varsha Kukafka we read how a mother at ninety-seven still recounts the near-loss of a then infant child to whooping cough and in “Paper Armor” by Cara Haberman, a simple sentiment “—Yes, I promise I will be with you” are the words spoken to a frightened patient. We find ourselves passenger to a drive home in “Homing Signals” by Sophia Wilson. The narrator “can’t sleep at night” and leaves the “city’s pandemically fractured centre” to enter a feeling of pervasive darkness; then light emerges. This light isn’t a natural or supernatural light, but a human-engineered light guiding her home.

Currently, I volunteer in a covid-19 vaccination clinic where without fail an elder’s eyes will warm when I wave them over, they will say something like “I haven’t been waved to in a year” or “Me? It’s not often people talk to me.” In all the darkness and sleepless nights, we are still humans capable of inventing light, capable of preventing empty highways.

Cole W. Williams is the author of Hear the River Dammed: Poems from the Edge of the Mississippi (Beaver’s Pond Press, 2017) as well as several books for children. Her poems have appeared in Martin Lake Journal, Indolent Books online, Waxing & Waning, Harpy Hybrid Review, WINK and other journals and anthologies. Williams is a student in the MFA program at Augsburg University in Minneapolis. Find out more about her work at colewwilliams.com

Mothers and Daughters: A Reflection on Cancer, Caring and Seeing the Whole Picture by poet Kathryn Paul

—After ‘Macroscopic” by Adela Wu (Spring 2021 Intima)

My mother and I were not close. I knew she wanted us to be, but I couldn’t do it her way. For most of my adult life, I kept my distance, emotionally and physically. We lived on opposite sides of the continent. In her 80’s, the creeping dementia my mother never discussed was overtaken by a cruel and much more terrifying diagnosis: Stage IV ovarian cancer.

Aided by her cancer-free twin sister, Mom endured multiple surgeries and two lengthy and debilitating rounds of chemo. Each time, her cancer came roaring back within weeks. Her surgeon suggested an experimental Round Three. Mercifully, her oncologist suggested hospice at home instead.

During the first year of Mom’s illness, I was trapped by my own cancer treatment, unable to participate in her care. I called daily, spoke with her, spoke with my aunt, asked about her pain, her “tummy trouble,” her ascites, and her white count. I took notes and dictated the questions to ask at her next appointment.

As soon as my doctors cleared me to visit her, I did. I was always on the verge of moving in with her, but never quite needed to do so. I flew back and forth. The more debilitated she became—by her cancer and her dementia—the more often I visited.

Adela Wu’s Studio Art piece “Macroscopic” simply and eloquently captures the changes in how I experienced my mother during those last months and weeks. The simplest things gave her joy: A small dish of ice cream. A pain-free nap on the down-stuffed cushions of her couch. Cuddles with her cats. A bird visiting the feeder outside her window.

Even as her disease spread through her body, even as she faded, my mom seemed to crystallize. She became, ultimately, the Essence of herself. And—just at the end—I finally saw her.

Kathryn Paul

Photo by Andrew Givhan

Kathryn Paul (Kathy) is a survivor of many things, including cancer and downsizing. Her poems have appeared in Rogue Agent, Hospital Drive, The Ekphrastic Review, Lunch Ticket, Stirring: A Literary Collection, Pictures of Poets and Poets Unite! The LiTFUSE @10 Anthology. Her poem “Dementia Waltz” appears in the Spring 2021 Intima.

Does the Patient Know the Prognosis is Terminal? A reflection by Julie Freedman

‘Does he know?’

The prognosis is terminal. No treatment will change that fact. His doctors know, but the patient, he seemingly does not.

In Phillip Berry’s essay, “Black Tango,” the narrator wonders if his patient knows his cancer will soon kill him (Please go read it, it’s beautiful, before I spoil it). He worries the patient is living “on fumes” of hope and resents the doctors who previously, falsely, pronounced him cured. He dreads telling him the truth. Finally, he sits down to talk with the patient and his wife. They already knew. In a sudden reversal, it is the patient who was protecting the doctor: “He saw me dancing with words, he read my evasions, and he waited. Waited until I was ready.”

Shakespeare, Stanzas and How We Think About Death by Albert Howard Carter, III, PhD

When my sonnet “All Tuned Up” appeared (Spring 2021 Intima), I was asked to write about another piece published in the journal. I chose “I Picture You Here, But You’re There” (Spring 2020 Intima) by Delilah Leibowitz. Her poem and mine both explore how we think and feel about death.

Read moreThe Body in Bloom: Thoughts on Two Artworks by Simona Carini

(c) Floral Anatomy by Kristen Kelly. FALL 2018 Intima

As a writer, to give life to a story, I reach for my pen and notebook, craft words into images, lines, sentences. I find it inspiring to explore how other artists use their preferred media to tell stories. In my poem “Young Woman Listens to Cyndi Lauper During Dialysis” (Spring 2021 Intima), I open a window into an experience of eating disorder. In contrast, two artists in the Fall 2018 Intima show us how our body can be seen as a garden of elegant shapes and rich colors.

Read moreHow a Doctor Learns to Act: A Reflection by Claire Unis, MD

“Am I becoming / something unfamiliar?” asks Lauren Fields in her poem “My First Mask Was a White Coat” and in that simple question she brings back for me the struggle of becoming. With our first medical school clerkships we don white coats and mimic our preceptors: some false confidence here, a prayer for invisibility there. Silent reassurances never spoken aloud: It’s okay to pretend at doctoring. That’s how you learn.

Read moreHow Touch Affects Healing, a reflection by Wendy Tong

In her Field Notes essay “Hand Holding” (Fall 2019 Intima), Dr. Amanda Swain describes the experience of beginning her surgery rotation as a third year medical student. In the early days of the rotation, she feels an intense sense of being out of place within the “intricately choreographed dance” of the operating room. But when the next patient is wheeled in, Dr. Swain is reminded of how a nurse once took her hand before she underwent surgery, the touch conveying an unforgettable message of comfort during a time of deep vulnerability.

Read moreOn Fathers, Love and “Exit Wounds” by psychiatrist and essayist Greg Mahr

I regularly attend a poetry critique group in Ann Arbor, MI called the Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle, named after the bookstore and tea shop where we used to meet before the pandemic. The experienced poets there have come to accept the sad and overly personal poems and flash pieces I write and help me craft them into something that sometimes almost sounds like real writing. One of them once told me, “You always write from a place of longing. That’s a good place to write from.” I realized he was right. I find it hard to share what I write with the people I love. When I am in a good relationship, I write about bad ones; when I love someone, I write about missing them.

Read moreAuscultating Meaning: Reflections on the Heart of Medicine by Marc Perlman

© Gordian Knot by Elisabeth Preston-Hsu Spring 2020 Intima A Journal of Narrative Medicine

From diaphragm to earpiece, a stethoscope dutifully chaperones a patient’s internal orchestra to a clinician’s ears. This facile acoustic communication not only allows a provider to screen for a wide host of cardiovascular, pulmonary and gastrointestinal anomalies, but it also may be a conduit for moral reflection.

Read moreDoctoring and Disobedience: Speaking an Important Truth, a reflection by Kelly Elterman

Sometimes, the truth can be uncomfortable. It can be difficult to hear and often, even more difficult to say. In her Field Notes piece entitled “Doctoring and Disobedience” (Spring 2020 Intima) Dr. Lisa Jacobs recalls her struggle with being told to hide the truth of a prognosis from an elderly patient with metastatic disease. Despite the instruction of her attending physician, and the decision of the patient’s family and ethics team to not speak of death to the patient, Dr. Jacobs feels compelled to let her cognitively-intact patient learn the truth. So strong is her conviction that she takes on considerable risk to her own career for the sake of bringing the truth to her patient.

Read moreHealing and Trauma: Recontextualizing Suffering by Sundara Raj Sreenath

Suffering due to trauma or illness often brings with it feelings of disconnect from the world as we knew it when we were healthy. The healthcare provider-healer, therefore, has an important opportunity to intervene in this unique setting and respond to the patient’s cry for help by offering a personal, humanistic touch and guiding them through trauma in addition to clinical management.

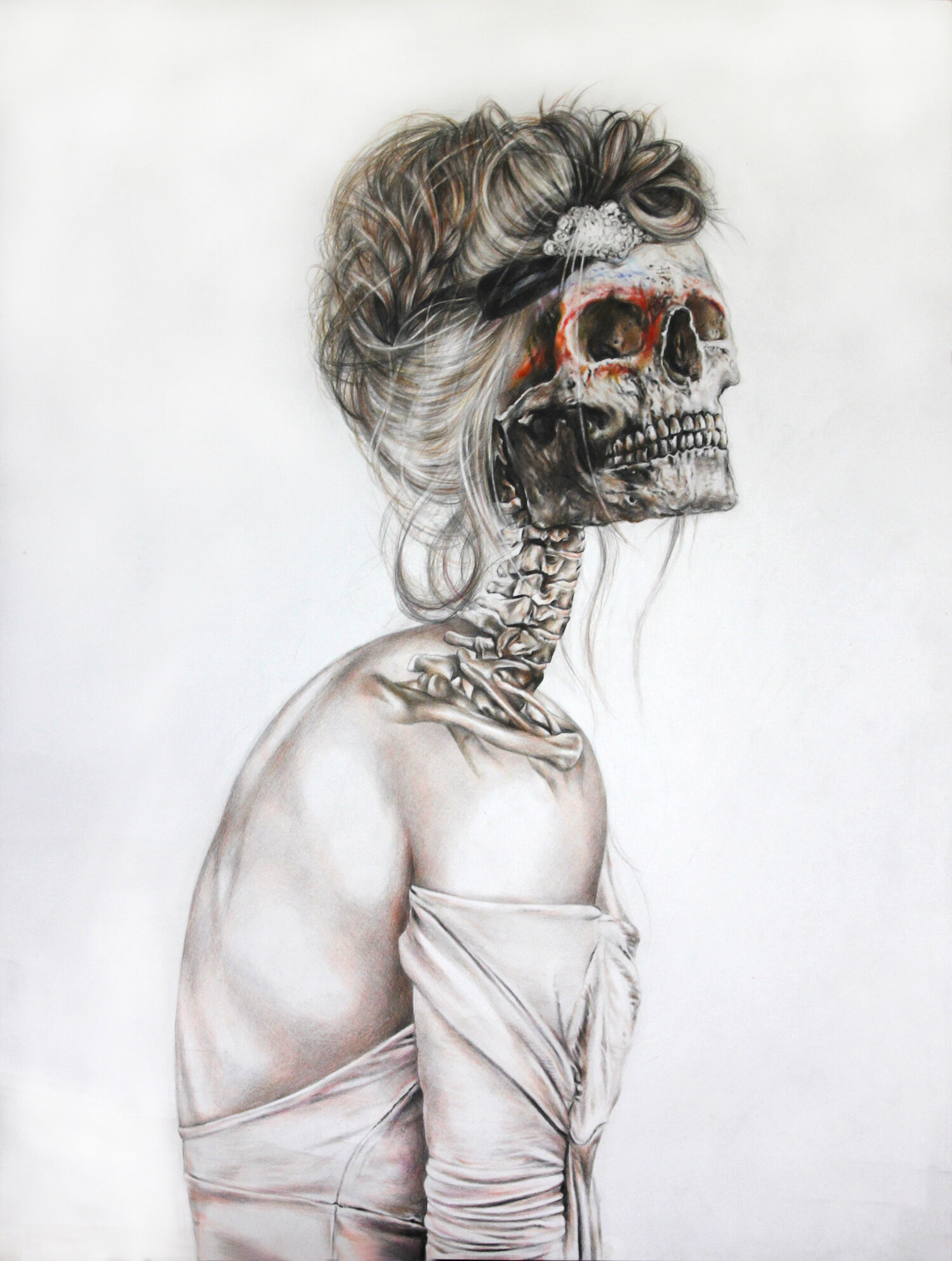

Read moreReimagining Chaos in Art and Poetry by Selene Frost

Anatomy of the Vogue by Meagan Wu. Fall 2017 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine

I’ve long been fascinated by the way structure informs poetics and the practice (and in this case—reception of medical care). In my piece “Field Notes on Form,” I extol the ways in which linguistic structure has the remarkable ability to organize our thoughts, increase our signal within the noise, and etherealize the mundane. In “Post NICU Villanelle,” Joyelle McSweeney uses language not only to remediate the chaos of loss and of leaving but also to deconstruct both the poetic form and herself.

Read moreThe Cost of Efficiency and the Price of Empathy, a Reflection by Jordana Kritzer MD

After the long hours and intense learning curve of my Emergency Medicine residency, I had become one of those efficient robots who could solve medical puzzles and save lives, but I felt empty, disconnected—the classic symptoms of burn-out. I was once a wide-eyed, empathetic intern constantly criticized for trying to solve their patient’s chronic issues. I remember one attending saying, “Figure out the least amount of things you need to do to rule out an emergency.” I see now that he was trying to teach me efficiency.

Read moreLife in the Gaps: How Illness Transforms Our Sense of Time by Renata Louwers

It was in those gaps, between our lived experience—the crushing uncertainty about how long my husband would live, the daily reality of his intolerable pain, and the abrupt shift from a life of joyful ease to one spent contemplating death—and the oncology profession’s standards of care, first-line treatments, and numeric pain scales that my frustration festered.

Read more