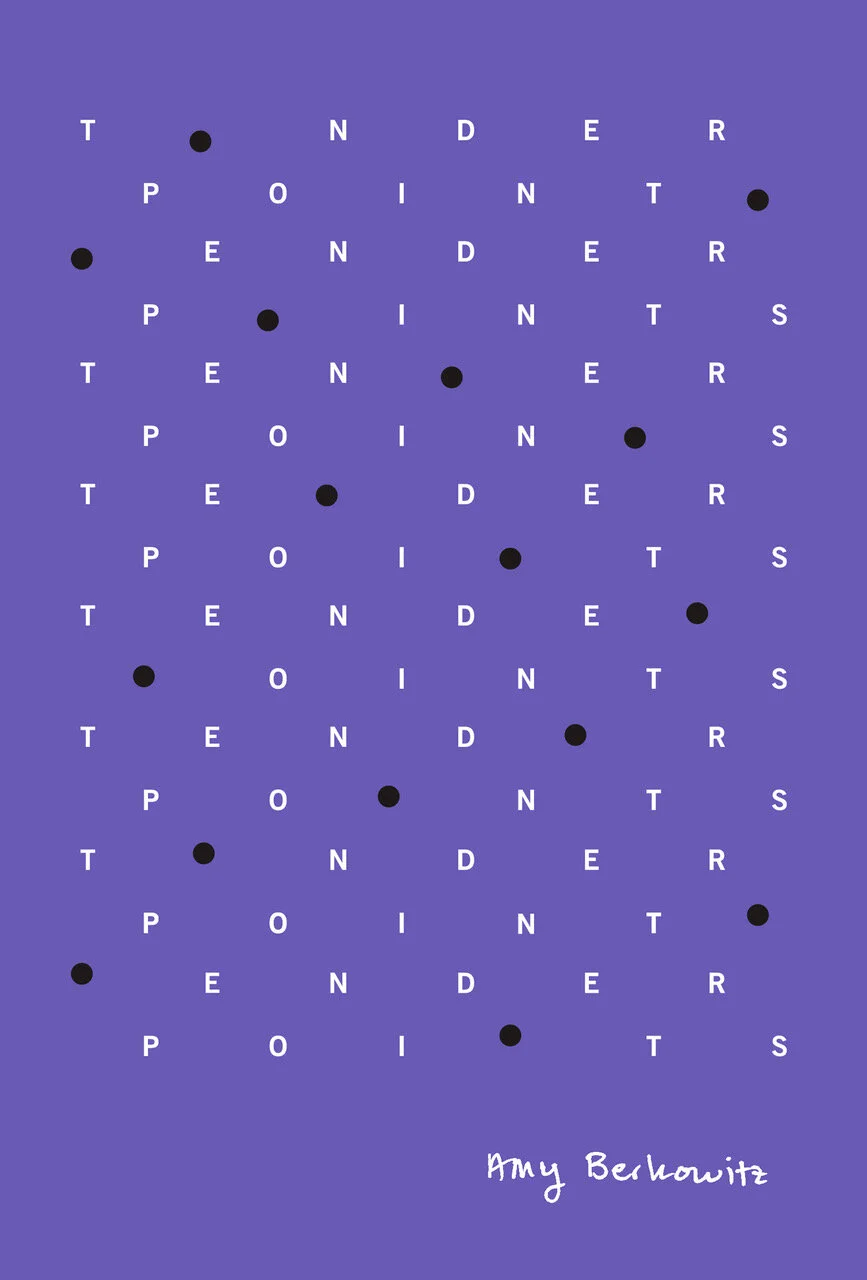

Amy Berkowitz is the author of Tender Points. Other writing has appeared in publications including Bitch, McSweeney’s, and Wolfman New Life Quarterly. amyberko.com.

Tender Points by Amy Berkowitz is a personal account of life with Fibromyalgia (FM), a condition that the author has and uses to explore topics frequently associated with the disease. The book, then, is also an account of terror, sexual violence, enduring, overcoming, adapting, being unbelieved and ignored. It is a book is about being a woman in a patriarchal culture.

Berkowitz’s essayistic nonfiction blends poetry, “listicle” summaries of a-day-in-the-life with chronic pain, segments from FM discussion boards, and reflections on historical discussions of pain and women’s health. Throughout, she demonstrates incisive wit and a tight control of language. Culturally wide-ranging, she draws on (among others) Freud, fiction writer Richard Brautigan, Sarah Winchester, the Riot Grrl punk-music movement, and Sex and The City, to texture and color and sound her work. Though each component only spans a single or handful of pages, she arranges every part to create a connected story. Thus the author leads us down a hallway of her own perspective on chronic pain. She is saying: I am a full person, with multidimensional ideas and arguments, and I suffer from chronic pain.

In the midst of this tour, we learn Berkowitz was raped at a young age by her pediatrician. It’s while remembering the incident years later that she began experiencing the symptoms of FM. At a later point an expert on sexual violence asks her if she was raped, and Berkowitz replies: “I don’t know.” The answer comes as a surprise; it is not immediately clear to her why she answers this way. “Who can argue with a stethoscope?” she writes. This invokes questions so often surrounding women as victims of rape, sexual violence, and toxic masculine cultural norms: why did she wait so long? Why did Dr. Christine Blasey Ford not speak up sooner? Or the accusers of President Trump or Harvey Weinstein? Why can’t a victim tell all the details clearly? Can we believe her? Throughout Tender Points, Berkowitz answers these questions through her story.

The author deftly uses form to underscore her sentences. Ample blank space throughout the book—some pages only have a few words—reminds us that pain can be as much about absence as it is about presence. Absence, in the sense of not being seen or heard, is part of everyday reality for many people suffering from chronic pain. Alternatively, absent from most people’s lives is relentless suffering and stress. The freedom that comes from pain’s absence is not something those with chronic pain can know.

Yet for all her truth telling, Berkowitz reaches some questionable conclusions about physicians and the field of medicine. For example, she uses Carl Morris’s Culture of Pain as a touchstone, equating the historical view of hysteria with the way we currently view FM, as a diagnosis in which mostly male physicians can imprison poorly understood female patients. She also revisits one of Morris’s more contested points, that pain should be viewed as a mystery, rather than a puzzle to be solved. This is a false dichotomy: a both/and approach is typically employed for poorly understood medical problems. Pain is a mystery and a puzzle, and it should be approached with deference to both. After all, as a result of problem solving and refusal to see it as purely a mystery, Hysteria has become (mostly) a bygone medical diagnosis.

But none of these dead-ends limit the power and utility of the book. Tender Points immerses the reader in the experience of someone who is suffering from chronic pain. Each page turns us to see, hear, feel, and gradually understand that experience. It’s not always clear, it’s not always clean, but it always crackles with bright personal truth.

In healthcare, many of us know we should believe women, and believe those with chronic pain. But clinical conditions mandate skepticism beyond the purely intellectual, and we are generally required to face a problem as a balance of both/and: believe and question. But we must do a better job at understanding the experience of those with chronic pain and FM to inform that balance.

I spent time listening to some of the bands Berkowitz references in her book. The song “Rebel Girl,” by Bikini Kill carries these lyrics: “When she talks, I hear a revolution.” The fulcrum of this line is “she talks, I hear.” That alone is a revolution for many of us, because hearing is necessary for understanding. And reading Tender Points is an excellent way of hearing—of listening—to better understand women with chronic pain and Fibromyalgia.—Britt Hultgren

Britt Hultgren. Photo by Allison Coffelt

Britt Hultgren is a resident physician with the University of Utah Department of Family and Preventive Medicine. Selected publications include The New England Journal of Medicine and a feature-series in Jordan Business Magazine.