From the author: Bone cancer in my cheek ended my career as an opera singer and brought me face to face with mortality, disfigurement, the meaning and uses of beauty—and a lot of left over pieces.

Read moreBetween Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of Life Interrupted by Suleika Jaouad

I had cancer in my early 30s. None of my peers had gone through that experience, and this was back in the early aughts, a few years before the birth of the social media industrial complex, so as I navigated this new space, I read cancer memoirs. A lot of them.

At first, I appreciated seeing my own experiences echoed on the pages – the time when the doctor fumbled the diagnosis, the time when locks of hair fell out, the time when a friend couldn’t cope so she disappeared. After a while, though, the stories I read started to have a sameness about them. A lot of doctors fumble diagnoses, a lot of hair falls out.

Twenty years later, I’m studying end-of-life narratives for my doctoral dissertation, and I’m still reading a lot of cancer memoirs. I grow pickier each year, but I’m happy to report that Suleika Jaouad finds fresh territory to explore with her well-crafted book Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of Life Interrupted.

Jaouad was 22 and working a paralegal gig in Paris when she learned she had acute myeloid leukemia, a disease usually found in people three times her age. She was living with Will, whom she had met in New York just a few months earlier, and their relationship forms the through line for the book as cancer shoves them past their meet-cute beginnings and moves them into the emotional turmoil of what ends up being years of treatment.

We get only Jaouad’s telling, of course, but she does not go easy on herself, describing her anger when he doesn’t give as much support as she wants, even as she shows us he was breaking with the effort to give what he did – especially considering he had never made any vows about sticking around “in sickness and in health.”

I squirmed under the tension around how much this provisional relationship could bear. At one point, Will, desperate for a respite from caregiving, floats the idea of joining friends for an out-of-state music festival, and we register Jaouad’s response:

“I wanted to be the graceful leukemic starlet who told him, Take as many breaks as you want, you deserve it, have a wonderful trip, my love, but there is spiritual exhaustion that comes with maintaining this kind of charade after a while. As a patient there was pressure to perform, to be someone who suffers well, to act with heroism, and to put a stoic façade all the time. But that night, I didn’t have it in me to listen to how hard my illness was on Will – how badly he needed a break when I didn’t have the option of taking a break from this body, from this disease, from this life of ours” (161).

Here is a side of cancer we never see in get-well cards.

The relationship is only one illustration of what can make cancer different for young adults; her professional life is another. Jaouad was floundering in the months after college with both yet-undiagnosed physical symptoms and with the existential questions of what do with her life.

She had fled to Paris with a vague idea of becoming a foreign correspondent in her father’s North African homeland. Suddenly, because of her illness, she was back in her childhood bedroom in upstate New York, rebalancing her fresh independence with her even newer vulnerability. There are the unexpected questions that arise that demand her to look into her future, one that’s almost impossible to foresee. Although she had barely thought about motherhood, for example, she finds herself having to remind her medical team to consider preserving her ability to have children.

Often-harrowing treatment consumes the next four years and takes us more than halfway through the book, which originated in a New York Times column. She finds a creative band of “young cancer comrades” that includes the poet Max Ritvo. Only three of the 10 were still alive by the time she writes the book.

The second section veers to another memoir device, the travelogue. She first visits India, then makes solitary sojourns to Vermont, leaving only the final quarter of the book for the 100-day, 15,000-mile U.S. road trip suggested by the book’s romantic cover photo, which shows Jaouad sitting atop a hipster-friendly 1972 Volkswagen camper van with her rescue dog, Oscar. Along the way, she visits people who responded to her newspaper columns because they connected to some part of her experience – people with serious illness, but also others, a grieving parent and a death-row inmate, who related to her narrative voice and found common ground with her illness experience.

The trip allows her physical and psychological space to reflect, leading to some of the book’s finest passages. After visiting Bret, a young filmmaker with lymphoma, she writes:

“I began to think about how porous the border is between the sick and the well. It’s not just people like Bret and me who exist in the wilderness of survivorship. As we live longer and longer, the vast majority of us will travel back and forth across these realms, spending much of our existence. The idea of striving for some beautiful, perfect state of wellness? It mires us in eternal dissatisfaction, a goal forever out of reach. To be well now is to learn to accept whatever body and mind I currently have” (274).

The meaningful interactions offset my sense that the trip has been manufactured for (or by) a book deal in the vein of memoirs like A.J. Jacobs’ My Year of Living Biblically and Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love; Gilbert even provides Jaouad with a book-jacket blurb. The feeling was only heightened when I realized she actually did the road trip in a borrowed old Subaru; the van was bought long afterward, as a reminder of one she saw during the trip, as she notes on the last page of the epilogue.

I wish her publisher had resisted this urge. The golden-yellow van makes a great photo, of course, but the quest it suggests plays neatly into conventional hopes for what the psychotherapist Kathlyn Conway calls the triumph narrative, where illness only makes us stronger and wiser. In fairness, Jaouad herself follows this route to close the book, declaring that she treasures her heightened awareness of her finitude even if her early adulthood was “wrenching, confusing, difficult – to the point of sometimes feeling unendurably painful … I would not reverse my diagnosis if I could. I would not take back what I suffered to gain this” (340-41).

This may be true, but the reflection comes together in less than two pages, suggesting her feeling during an NPR appearance when she was “determined to end the interview on a strong note” (135).

And then there’s the book’s subtitle phrase “life interrupted,” no doubt meant to remind readers of her newspaper column of that same name. The allusion to Girl, Interrupted, Susanna Kaysen’s 1993 memoir of mental illness is especially clumsy coupled with the reference to Susan Sontag in the main title – if not as profound as Sontag, Jaouad’s writing certainly stands on its own. More significantly, however, the phrase implies that her illness was not part of her life. Her book tells a different story.—Cherie Henderson

Cherie Henderson

Cherie Henderson is a doctoral candidate in communications at Columbia University. Her dissertation explores stories told by younger adults with terminal illness, and what we can learn from them about the cultural models of behavior for the ill and dying. She has also worked at the intersection of death and humor. Henderson, who has initiated and led writing workshops for patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering cancer center, holds a master’s degree from Columbia in narrative medicine and was a faculty associate, fieldwork supervisor and post-graduate fellow in that program. Earlier, she was a staff editor and reporter at The Miami Herald and The Associated Press. She graduated from The University of Texas at Austin in journalism.

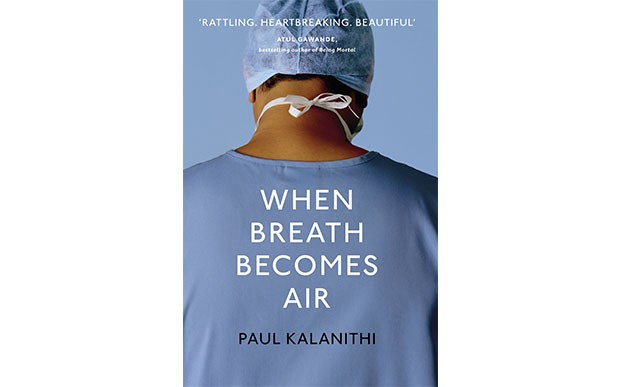

When Breath Becomes Air

It is often startling and unsettling to read the work of a writer who has passed. In some ways, this is the norm—it’s rare that students in school read books by writers still alive. The distinction, however, is this: those writers—Shakespeare, Joyce, Woolf, even Salinger, who only passed a few years ago—aren’t writing about their descent into death as they lived it. Paul Kalinthi’s When Breath Becomes Air details the last year of his life as he, a neurosurgeon, fights metastatic lung cancer. It sounds depressing in summary, though the book lacks any trace of self-pity or of anger. It is written with intelligence and with honesty, a product of reflection and insight. We can trust him, the reader knows, to present his story to us the same way we could have trusted him to operate on our brains. His humanity is tangible.

The most striking observation about the book is its voice. Despite his death last year, Kalinthi’s voice is rich and alive on the page, and he speaks not to doctors or to cancer patients but to anyone who is interested in the question of what it means to live and to die with humanity. Kalinthi spent his life devoted to this question, always torn between a career in the humanities and one in medicine. He ultimately pursued both, first a Master’s degree in literature and then medical school for neurosurgery. “The call to protect life—and not merely life but another’s identity; it is perhaps not too much to say another’s soul—was obvious in its sacredness,” he explains about neurosurgery. “Before operating on a patient’s brain, I realized, I must first understand his mind: his identity, his values, what makes his life worth living, and what devastation makes it reasonable to let that life end. The cost of my dedication to succeed was high, and the ineluctable failures brought me nearly unbearable guilt. Those burdens are what make medicine holy and wholly impossible: in taking up another’s cross, one must sometimes get crushed by the weight.”

In the book’s introduction, Abraham Verghese makes note of Kalinthi’s “prophet’s beard,” an idea his wife Lucy later clarifies as an “I didn’t have time to shave” beard—but to readers of his book, it’s clear that Kalinthi was, in fact, a prophet in many ways. His observation that “life isn’t about avoiding suffering,” which he acknowledges in his and Lucy’s decision to have a child despite his prognosis, demonstrates the ways he understands the world beyond his own life. Experiencing illness as a doctor—and a sensitive, empathetic one—adds a moral gravity to his words.

The Kalinthi family: Paul, Lucy, and baby Cady

Paul Kalinthi passed away surrounded by his family when his daughter Cady was eight months old. “When you come to one of the many moments in life where you must give an account of yourself,” he tells his daughter in the final paragraph, “provide a ledger of what you have been, and done, and meant to the world, do not, I pray, discount that you filled a dying man’s days with a sated joy, a joy unknown to me in all my prior years, a joy that does not hunger for more and more but rests, satisfied. In this time, right now, that is an enormous thing.” His life was cut too short, though his extraordinary accomplishments in his thirty-seven years might make you reevaluate how you’ve spent your time, what you’ve taken for granted, and how to leave an imprint as large as his. —Holly Schechter

HOLLY SCHECHTER teaches English and Writing at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan. She graduated from McGill University with a degree in English Literature, and holds an MA from Teachers College, Columbia University. She is active at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, where she received excellent care as a patient, and in turn serves on the Friends of Mount Sinai Board and fundraises for spine research. Her piece "Genealogy" appeared in the Fall 2014 Intima.