When neurointensivist Dr. Eelco Wijdicks published the original Neurocinema: When Film Meets Neurology in 2014, his collection of film essays summarizing the portrayal of major neurologic syndromes and clinical signs in cinema served to underscore the field’s existence by being its premier textbook. Therein the medically-inclined movie buff or the film-frenzied clinician could explore medicine as it appeared on the big screen and better understand what the effects of medicine on film have played in our cultural milieu over time.

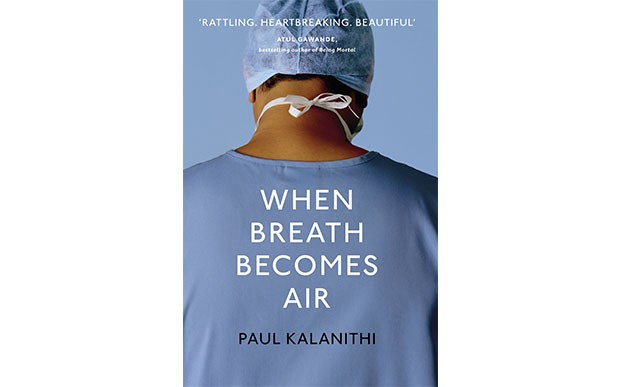

Read moreWhen Breath Becomes Air

It is often startling and unsettling to read the work of a writer who has passed. In some ways, this is the norm—it’s rare that students in school read books by writers still alive. The distinction, however, is this: those writers—Shakespeare, Joyce, Woolf, even Salinger, who only passed a few years ago—aren’t writing about their descent into death as they lived it. Paul Kalinthi’s When Breath Becomes Air details the last year of his life as he, a neurosurgeon, fights metastatic lung cancer. It sounds depressing in summary, though the book lacks any trace of self-pity or of anger. It is written with intelligence and with honesty, a product of reflection and insight. We can trust him, the reader knows, to present his story to us the same way we could have trusted him to operate on our brains. His humanity is tangible.

The most striking observation about the book is its voice. Despite his death last year, Kalinthi’s voice is rich and alive on the page, and he speaks not to doctors or to cancer patients but to anyone who is interested in the question of what it means to live and to die with humanity. Kalinthi spent his life devoted to this question, always torn between a career in the humanities and one in medicine. He ultimately pursued both, first a Master’s degree in literature and then medical school for neurosurgery. “The call to protect life—and not merely life but another’s identity; it is perhaps not too much to say another’s soul—was obvious in its sacredness,” he explains about neurosurgery. “Before operating on a patient’s brain, I realized, I must first understand his mind: his identity, his values, what makes his life worth living, and what devastation makes it reasonable to let that life end. The cost of my dedication to succeed was high, and the ineluctable failures brought me nearly unbearable guilt. Those burdens are what make medicine holy and wholly impossible: in taking up another’s cross, one must sometimes get crushed by the weight.”

In the book’s introduction, Abraham Verghese makes note of Kalinthi’s “prophet’s beard,” an idea his wife Lucy later clarifies as an “I didn’t have time to shave” beard—but to readers of his book, it’s clear that Kalinthi was, in fact, a prophet in many ways. His observation that “life isn’t about avoiding suffering,” which he acknowledges in his and Lucy’s decision to have a child despite his prognosis, demonstrates the ways he understands the world beyond his own life. Experiencing illness as a doctor—and a sensitive, empathetic one—adds a moral gravity to his words.

The Kalinthi family: Paul, Lucy, and baby Cady

Paul Kalinthi passed away surrounded by his family when his daughter Cady was eight months old. “When you come to one of the many moments in life where you must give an account of yourself,” he tells his daughter in the final paragraph, “provide a ledger of what you have been, and done, and meant to the world, do not, I pray, discount that you filled a dying man’s days with a sated joy, a joy unknown to me in all my prior years, a joy that does not hunger for more and more but rests, satisfied. In this time, right now, that is an enormous thing.” His life was cut too short, though his extraordinary accomplishments in his thirty-seven years might make you reevaluate how you’ve spent your time, what you’ve taken for granted, and how to leave an imprint as large as his. —Holly Schechter

HOLLY SCHECHTER teaches English and Writing at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan. She graduated from McGill University with a degree in English Literature, and holds an MA from Teachers College, Columbia University. She is active at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, where she received excellent care as a patient, and in turn serves on the Friends of Mount Sinai Board and fundraises for spine research. Her piece "Genealogy" appeared in the Fall 2014 Intima.