Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative condition clinically identified by the hallmark features of shaking, stiffness and slowness. PD is also marked by a multitude of non-motor symptoms like constipation, cognitive changes and sleep disorders. Any number of symptoms and intensities can exist in each patient, leading to a remarkably heterogenous patient population. While effective symptomatic treatments exist, the only known means of quantitatively slowing progression to date is exercise, specifically cardiovascular exercise that increases heart rate (1).

Read moreDementia 21 by Shintaro Kago

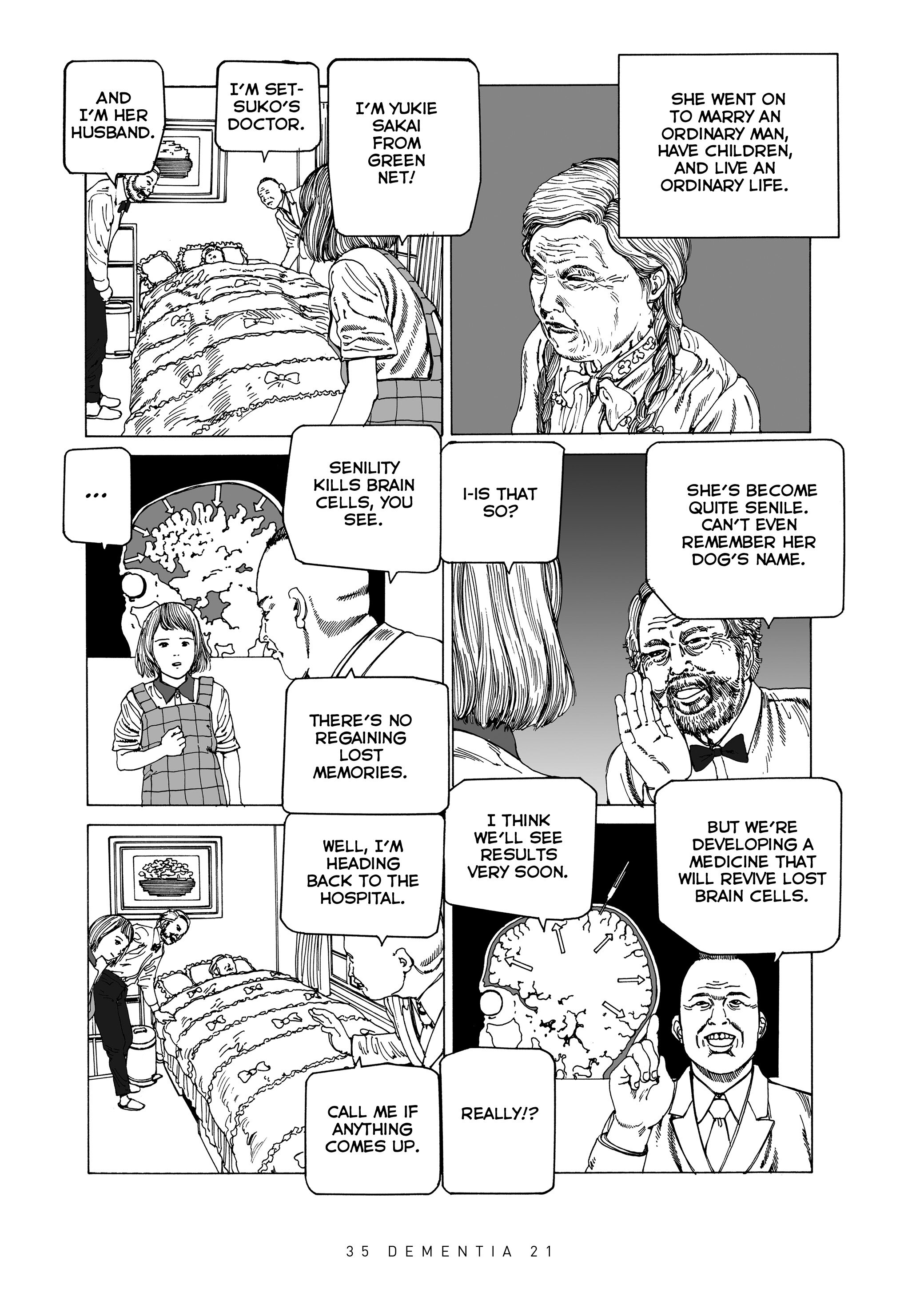

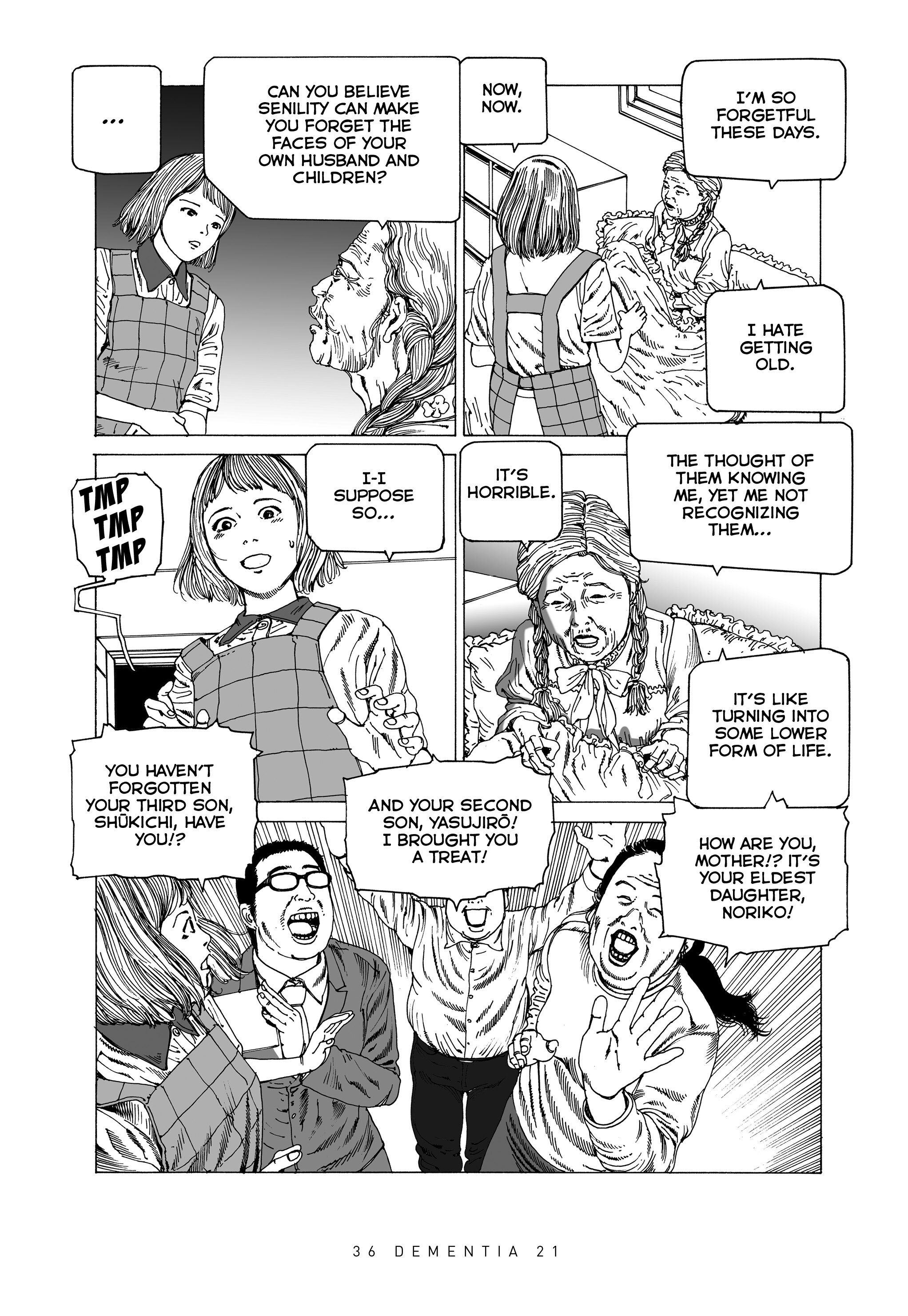

Dementia 21 is a horror graphic narrative by Shintaro Kago, published by Fantagraphics Books

Dementia 21 is twisted. I mean that in the best possible way.

From the eerie, delicious mind of Shintaro Kago, the Japanese ero guro nansensu (horror mixed with surrealism) manga artist, Dementia 21 is a chronicle of surreal stories about Yukie Sakai, a home health aide. The horror graphic narrative is twisted and destabilizing, with characters who transform throughout the story, revealing different sides. What you expect is never what the story—or characters—turn out to be, and that is the beauty of what Intima sees as a graphic medicine classic, the first of several translations of Kago’s work that Seattle-based publishing company Fantagraphics Books will release.

Kago’s stories in the volume follow the hardworking Yukie through days fraught with unexpected drama from her patients, their family members and others (see below for a short example). She tries to handle them as they come at her, and she usually can cope with the weirdest situations. But as fellow home health aides become jealous of Yukie’s ability to get the top score at the company each month, a rival healthcare worker plots to send her to difficult clients to drop her score. The first home Yukie gets sent to turns out to be a death trap, where five previous home health aides have met strange and freak accidents. While cleaning, Yukie comes across a secret panel depicting the faces of the five previous aides when suddenly, the elderly patient Yukie is helping attacks her. Yukie survives, however, because the old woman needs her heart medication, and ironically, in exchange for the medication, Yukie gets a high score.

The contest for top home health aide quickly devolves into the absurd. The second home Yukie is sent to has three elderly women. Caring for three people is already exhausting enough when the next day, those three women become six. The next day, six become twelve, until the whole house is crammed with elders. Strangers dump their relatives at the house, and Yukie is appalled. “How can you let yourselves be treated this way?” she cries to the patients. “Thrown out like trash by your own flesh and blood! DOESN’T THIS BOTHER YOU AT ALL!?.” It’s a question they are powerless to answer.

Every chapter begins with a full-page spread, one of this graphic artist’s signature techniques. Sometimes Yukie is crawling out of her own face; sometimes she is fending off danger, hair flying; sometimes she is being strangled and swallowed by wires. Often, the backgrounds of panels convey horror, fear, and confusion with layered visual elements—brush strokes, whorls, gothic detailing—that portray a chaotic emotional reality. These graphic strokes reverberate and tantalize the reader but also create a sense of horror about the confusion of health, illness and difficulties of healing and healthcare.

This powerful narrative contains multiple meaning: Part social commentary and satire, part menacing story colored by greed and selfishness, part narrative on thankless work, Dementia 21 is a transgressive form of graphic medicine. When I read other memoirs on aging and dementia, such as Joyce Farmer’s Special Exits and Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, I sense fear and anxiety, trembling and loss. When I read Kago’s book, however, it’s a different energy: one tinged with madness and imagination. It reads like a dream: What should we believe? What should we hold onto? What parts strike us most, and what does that say about us?

Dementia 21 is the myth of Sisyphus through a Japanese lens, with an enthusiastic healthcare worker tirelessly pushing against obstacles to make a difference while also making a living. At its core, the book is a graphical exploration of dementia and aging and its accompanying themes of abandonment, forgetfulness, senility, competition, technology, division and difference, abuse, and bullying. Ultimately, it is an eye-popping and painful story that explores the meaningfulness of life by focusing on the elderly and those who care for them.

Over thirty years since he debuted his first book, Comic Box, Kago continues to cross boundaries most other manga artists won’t go near by subverting expectations and breaking the fourth wall. His aesthetic is akin to shifting on soft soil, wallowing in shit (literally), its narrative dark but laugh-out-loud funny. He forces you to push your boundaries to the point of discomfort, and challenges you to stay there.

Dementia 21, Vol. 2 is scheduled for release in early 2020.—Jane Zhao

Jane Zhao

Jane Zhao is a lover of comics because when she has no brain or patience for words, she can escape into image. She is a graduate of the Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University and studied neuroscience at McGill University. She currently works in research in Canada. Talk to her about poetry, Donna Haraway, health policy, and muscle pain.

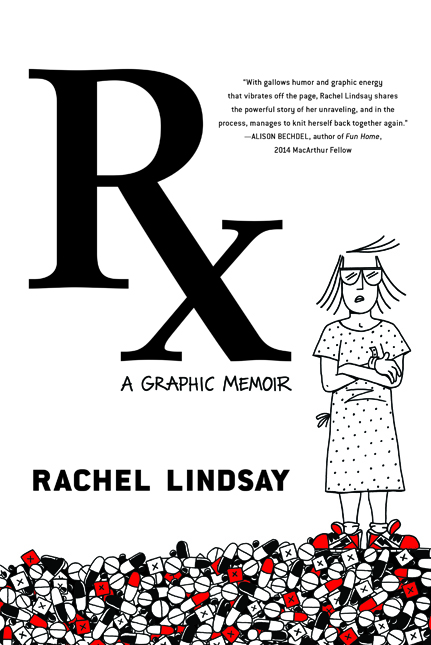

RX: A Graphic Memoir by Rachel Lindsay

Though much is taken, much abides: RX: A Graphic Memoir on corporate America and bipolar disorder

RX: A Graphic Memoir by Vermont-based cartoonist Rachel Lindsay is a memoir borne out of passion, determination, and commitment. Each chapter is short and episodic, and provides a chapter in the story of her unraveling: her time committed to a mental health institution and how she got there. Lindsay writes with a wry dark humor about her struggles to maintain stability with bipolar disease while working in a corporate job.

At nineteen, Lindsay was diagnosed with bipolar disease, a mental illness characterized by episodes of mania and depression. Staying sane becomes her primary objective and the medication her psychiatrist prescribes her helps keep her sane. Lindsay describes this rhythm of her sanity in three panels like a mantra: “Chug. Crush. Toss.”

Rachel Lindsay

Lindsay, whose comic strip, “Rachel Lives Here Now,” about her life as a New York transplant in Vermont, appears weekly in Vermont’s statewide alternative newspaper, Seven Days , has created a memoir that serves as a timely narrative for what many are experiencing in the United States. For the author, as with other Americans with pre-existing conditions, her corporate job is a means to an end, providing her with health insurance and prescription medication coverage. Despite feeling unhappy at her work, she continues at her job. She gets a promotion, which means she gets thrust into the corporate pharmaceutical world and works on a marketing campaign for an antidepressant, Lindsay continues to feel even more trapped.

As a graphic memoir, Lindsay’s style is frenzied, a visual staccato beat that moves her narrative along. The lack of gutter space makes the narrative feel overwhelming at times, yet each panel is concise and detailed. Often metaphorical, her chapters begin with a reflexive lens into the story. In one, she appears in a straitjacket. In another, she’s an “urban badass” ripping her way out of wall graffiti to symbolically step on the dead wind-up toy of her in the first chapter, sunglasses on, smoking, and giving the finger.

RX is also a book about a millennial, a millennial with a mental health condition. Trying to find balance between where you are and where you feel you ought to be, I identify well with that feeling. At a party in Brooklyn in 2010, a partygoer says to Lindsay, “Screw your corporate job and really commit yourself to your art. You’re really talented!!” And throughout her memoir, she struggles to find a creative outlet while maintaining her corporate veneer. Quite literally a wolf in one chapter, dressed in sheep’s clothing, she shows us the precariousness of just passing. And its toll on her mental health.

In her interactions with the system, whether this is the healthcare system, the corporate capitalist system, or the criminal justice system, the graphic writer echoes the frustration and hopelessness of feeling trapped. This shapes her story. The day after she is committed, Lindsay sits alone in a cell. “It’s easier to be angry than sad,” she writes. “Despite the psychiatrist I hadn’t stopped seeing, despite the pills I stopped taking, I sat tagged and overmedicated in a new prison – …waiting to be corrected to fit someone else’s definition of sanity.”

The memoir ends with recognition of the system she is beholden to—though much is taken, much abides. She writes with insight from her struggles with sanity and insanity and the work it has taken to get her to today. Lindsay dedicates the book to Burlington, Vermont, where she currently resides. Though her ending feels abrupt—How did she get where she is now? What happened after moving back in with her parents? What headspace is she in now? —Lindsay writes with calmness, reflection, and grace. This book is a testament of her voice.—Jane Zhao

Jane Zhao

Jane Zhao is a lover of comics because when she has no brain or patience for words, she can escape into image. She is a graduate of the Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University and studied neuroscience at McGill University. She currently works in research in Canada. Talk to her about poetry, Donna Haraway, health policy, and muscle pain.