In A Body Made of Glass: A Cultural History of Hypochondria (Ecco, Harper Collins, 2024), author Caroline Crampton combines what she refers to as a cultural history of hypochondria with a memoir of her experiences with anxiety disorder, allowing the history of it to inform her life and vice versa. Lest readers think they have nothing to learn about their own lives from a study of hypochondria, especially if they’ve never experienced it before, Crampton, a writer and critic who lives in England, reminds them that hypochondria has much to teach them about health. She goes even further by connecting the disease to gender and the mind-body divide.

Read moreShow Me Where it Hurts: Living With Invisible Illness by Kylie Maslen

Show Me Where it Hurts by Kylie Maslen

Kylie Maslen’s critically acclaimed non-fiction essay “I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Not Okay “ took a new form on shelves worldwide in 2020: The essay became the first chapter of Maslen’s experimental book Show Me Where it Hurts: Living With Invisible Illness. Like her essay, the book has met with success: it was shortlisted for Non-Fiction in the 2021 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards and named among Guardian Australia’s 20 best Australian Books in 2020.

Author Kylie Maslen . Learn more about her work at kyliemaslen.com

Photo by Lauren Connolly

As Maslen herself says, her book is a part of a growing trend of Australian “sick lit” – literature that deals with life with chronic illness. “Living with invisible illness poses a unique challenge,” Maslen explained we spoke via Zoom, “in that you’re constantly having to fight for attention because things are not self-evident.” Her collection of essays primarily focuses on endometriosis and bipolar disorder and brings to light conditions that are not well known or understood but are quite common. Endometriosis alone affects 1 in 10 women and its issues create complications we often choose to dismiss or ignore.

The topic of the book might sound a bit heavy – and at times it is – but Maslen managed to create a Millennial masterpiece. It is many things: confessional literature, a review of pop culture and a fight for disability awareness and representation all at once. A source of both tears and laughter, the book comes with an important message. As a part of pop culture itself, it manages to entertain nevertheless.

The nature of the book is already illustrated in the opening essay, where Maslen movingly writes about endometriosis, suicidal ideation and memes all in one text, as the following illustrates:

The very nature of chronic illness lends itself to isolation. Time spent at home resting, time spent in waiting rooms, time spent in hospital, time spent recovering.

Things I want to say:

I don’t know how long I can keep doing this.

I can’t do anything nice for myself because I spend so much money on staying alive.

Instead I post a meme of SpongeBob walking into a room with an exaggerated swagger. The caption reads ‘walking into your doctor’s office’.

The receptionist at my GP’s rooms says, ‘Take a seat, Kylie’ when I walk in the door. The frequency of my visits spares me the time it takes for him to look me up on the system and confirm my appointment; he no longer asks, ‘Is this still your current address?’ before letting me sit down. I’m grateful that he can see my exhaustion and helps me in this small but not insignificant way, but I’m saddened that my life looks like this at such a young age.

A key theme in chronic-illness memes is conversations with ‘normies’ (those who are not chronically ill or disabled). Specifically, she chronicles their refusal to listen, an inability to empathize with others’ pain or the quickness to dispense unsolicited advice about symptoms and illnesses of which they have no lived experience.

Things people say:

‘You don’t look sick.’

‘You look much better than last time I saw you.’

‘It’s good to see you with some colour back in your face at least.’

Many of us with chronic illness are often housebound. Unable to socialize with family, friends or colleagues we go online to interact with others. We are also searching for people who understand.

Peer support through social media offers a source of experiential knowledge about illness. It gives us a way to normalize pain and a life lived with chronic illness. That can take the form of sharing stories and asking questions, but often we communicate through chronic-illness memes, which are a simple visual means of conveying complicated emotions and frustrations, as well as a way to add humour to our heavy conversation. Using memes—images or videos that are already widely shared – with context tailored to illness communities allows those of us who feel socially isolated by circumstances beyond our control to connect with the broader zeitgeist.

Maslen connects with readers, especially those of her own generation, with her daring honesty. The author discusses sex, loneliness, mental health struggles and the burden of chronic pain as well as pop icons, her favorite TV shows, books and movies. In one essay, the writing is raw and dark, disclosing extremely intimate episodes of alcohol and prescription drug abuse as well as Tinder dates gone wrong due to endometriosis; another essay is a playlist, where each song serves as a tool to dig deeper into her own headspace. We are presented with an analysis of SpongeBob SquarePants and an ode to Beyoncé on the one hand, and on the other we witness Maslen thoughtfully posing for Instagram, choosing what to share and how, and comparing her life to the curated online lives of those who are well. It is this combination of different approaches to the same topic that enable the book to be a refreshingly accurate description of an entire life, warts and all, of a person just like any other Millennial—having to deal with the burden of chronic illnesses on top of it all.

This aspect of her narrative is what made it stand out from the rest of “sick lit” for me personally. Not much younger than Maslen, I, too, suffer from endometriosis. I’m often bedbound, scrolling through memes about menstruation and ‘endo life,’ laughing out loud and sharing the best ones with my online support groups and trying to communicate my condition with others through Instagram stories. I am yet to find a book on the subject that so fully resembles my own life. I can say with no hesitation that Maslen managed to do what all illness narratives aim to do – she wrote a book that connects with those who experience similar things on a very deep level. This makes the reader feel validated and less alone. It is, however, written in a welcoming way should it fall in the hands of ‘normies’ who are willing to learn more about what it is people like us experience.

There is a running joke in the endometriosis online community: We are the worst club with the best members. Nobody wants to be a part of this club, but everybody is offered a level of understanding that can hardly be found elsewhere as our situations are so particular, very individual yet somehow the same. In Maslen, I immediately recognized an #endosister as we say. Having heard that I would be doing this review, Maslen felt the same when she “Instagram stalked me.” It is for this reason, as well as being a genuine fan of the book, that I was thrilled when Intima decided to reach out to Maslen and ask her for an interview.

Maslen agreed to have a virtual sit down with the journal’s editor Donna Bulseco and myself, and across time zones, each cozy on our own continent, the three of us had a wonderful online chat about chronic illness, social media, narrative medicine and the possible impact of books such as this one on society at large. It was my pleasure to chat with Kylie, and I hope it will be yours to listen to what we each had to say. —Alekszandra Rokvity

Alekszandra Rokvity is a Serbian-born writer and PhD candidate working on her doctorate between the Karl Franzens University of Graz in Austria and the University of Alberta in Canada. She specializes in cultural studies and medical humanities. Her academic interest lies in the experiences of women with endometriosis within the healthcare system. Her doctoral dissertation is a case study of endometriosis that explores the connection between gender bias in the medical community and the social discourse surrounding menstruation.

Ms Rokvity has previously taught in Austria, Canada, Vietnam and is currently teaching in Belgrade, Serbia. An avid activist for women's rights, she cooperates with various NGOs such as the London Drawing Group (UK) and Vulvani (Germany).

Read more of her work on Medium.

The War for Gloria by Atticus Lish

Fiction has the ability to bring a world to life, to offer other viewpoints and ways of looking at the world, and it also has the ability to put us in another body in order to give us the experience of a disease or condition. In Atticus Lish’s excellent new novel The War for Gloria (Knopf, 2021), the disease is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease. The story is told from the perspectives of Gloria and her son Corey, who is a young teenager when Gloria is diagnosed with ALS. Lish, whose novel Preparation for the Next Life won the 2015 Pen/Faulkner Award, brings to life the world of working class Boston suburbs.

Departure from the Darkness and the Cold: The Hope of Renewal for the Soul of Medicine in Patient Care by Lawrence J. Hergott, MD

The balm for this difficult year can be found in the pages of Departure From the Darkness and the Cold: The Hope of Renewal for the Soul of Medicine in Patient Care (Universal Publishers) by Lawrence J. Hergott, MD. This collection of essays and poems seeks to renew the “soul of medicine,” constantly being threatened by competing pressures commodifying medicine. Both a retreat and a back-to-basics call for engagement, Hergott’s poignant writing confronts the most unifying themes of humanity: purpose, loss, connection and more.

In the essay “The Time of the Three Dynasties,” Hergott reckons over the tragic death of his farmer brother-in-law, comparing the similarities of his hard labor and work/life imbalance to a life in medicine. The lives of him and his medical colleagues are prestigious but not free from heartbreak: a letter from a neglected daughter, a distant spouse, never making it home before the 10 p.m. news are the emotional fall-out from a life of clinical commitment. He confronts fellow physicians with difficult questions such as “How much work and reward are enough? How much is too much? Who has control? Do we know the real cost? Who pays the price?”

In the tender poem “Loving Her,” a patient visits his late wife’s grave daily. The visit is more event than chore, more conversation than monologue. This is a clinical encounter with “clinical concerns aside,” where a physician is simply happy for his patient and the content days he spends “near her, or what was left of her, in the ground and in his heart.” The poem is a testament to really listening and knowing who and what is important to a patient, a person with a life outside the exam room that a physician can only begin to fathom.

Lawrence J. Hergott, MD, author of Departure From the Darkness and the Cold: The Hope for the Soul of Medicine in Patient Care

Similarly, in “The Absence of Something,” the grief and loss patients experience are no different than that experienced by physicians. Hergott is able to relate to his patients’ losses because he too has suffered an incalculable one—the death of his son. “While the circumstances of our loss are uncommon, our suffering is not extraordinary.” He has learned of the “different kinds of absences,” like the loss of personhood in dementia or stroke, committing to always attend to these absences like physiological maladies.

The author delivers hope and reassurance to the surgical patient in the poem “A Small, Sacred Space.” He weighs the post-surgical outcomes of normalcy, complication, and tragedy all with loving promise. “You will wake up to no difference between who you are and who you are.” A humanistic take on the informed consent conversation, he insists, “You will not be alone. You will not be apart.” Rather than instilling false hope, Hergott offers love no matter the result.

In documenting his own lessons and heartache in medicine and in life, Hergott offers a manual of wisdom to fellow physicians on how to humanize themselves, their patients and one another. Each poem and essay is a portal into how to frame issues in medicine in ways that can rejuvenate and tackle the burnout that is so widespread to the profession. Medical students, trainees and seasoned physicians alike can all encounter self-transformation in this poet-physician’s timely collection.—Angelica Recierdo

Angelica Recierdo

Angelica Recierdo works as a Clinical Content Editor at Doximity in San Francisco, CA. She received her Bachelor of Science in Nursing from Northeastern University and her M.S. in Narrative Medicine from Columbia University. Angelica was also a Global Health Corps Fellow in 2016-17. She has worked at the intersection of health and writing/communications, specifically in the fields of healthcare innovation, health equity, and racial justice. Angelica is a creative writer, and her work can be found in Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine, Literary Orphans, HalfwayDownTheStairs and The Huntington News, among others. Her essay “Coming Out of the Medical Closet” appeared in the Spring 2014 Intima.

In Two Voices: A Patient and a Neurosurgeon Tell Their Story by Linda Clarke and Michael Cusimano

Linda E. Clarke

Michael Cusimano

“I’d ask him if it’s normal to still be thinking about it this far on.”

So goes the central question and literary impetus for In Two Voices: A Patient and a Neurosurgeon Tell Their Story (Pottersfield Press), writer Linda Clarke’s memoir of her life as a clinical ethics educator and (current) health humanities practitioner, patient and “healthy” body, co-written with the surgeon who removed the colloid cyst that was in her third ventricle. The structure of the book is unique: Clarke explores the question of whether (and how) normal life returns after a traumatic medical event through retrospective emails with her doctor, Michael Cusimano, twelve years after her surgery. By narrating the dual perspectives that co-construct and police the normalcy of medical identity, In Two Voices also brings to life the co-existent reality—and the shame and fear—that can continue to shape both doctors and patients, even after surgical success.

The premise of In Two Voices is exactly right, from our perspective as scholars and activists in the medical humanities: Love, respect, trustand patience are what is needed to further the professional work of maintaining ethical doctor-patient relationships. But if the essential question of a book review is Would you recommend this book?, the answer when writing to the readers of intima is a bit tricky. After all, the field of medical narrative is no longer exploding; in fact, it has supernova-ed. Two decades after the narrative turn in the humanities toward stories about health, illness and the clinical encounter, how do you determine whether a work, however heartfelt, provides revelations and experiences worth the attention and time of those in the field?

That said, taking a formal cue from In Two Voices, we believe we can use the co-authored narrative architecture Clarke and Cusimano construct (i.e., curated email exchanges) to model or “aesthetically enact” (as we have dubbed it in public health advocacy contexts) a more robust methodology for evaluating and triangulating the reliability (and unreliability) of co-created medical narratives. In our collective ‘unreliable’ review in three voices, we hope to not only provide a lens for scholars and practitioners to read In Two Voices (and other patient memoirs) but all of the co-authored narratives that circulate in hospitals, doctors offices, and scholarship in the medical humanities.

So before we get into the weeds of narrative theory and public health, let’s start with that first Aristotelian question of literary criticism: How did In Two Voices make you feel, and what formal techniques led to those feelings?

Amanda Ahrens: There is an openness that exists between Clarke and Dr. Cusimano throughout the story. Because of this, In Two Voices doesn't hold back anything. It does not spare any detail or emotion. The story showcases the setting and the people in a way that puts the reader right in the middle of each scene. Most importantly, it simultaneously puts you in the minds of Clarke and Dr. Cusimano.

Steven Pederson: As Clarke begins talking about the impetus for co-writing the book with Dr. Cusimano, she explicitly draws attention to the fact that “the personal experience of the surgeon usually remains unknown” in the narration of medicine. Right up front she is emphasizing the need for narrative structure that accounts for the experiential context of the practitioner as well as the patient. This dual narration is carried out in a constant switch between different segments of both Clarke’s and Dr. Cusimano’s narratives in ways that allow them to parallel each other, contrasting Clarke’s “Opening” with Dr. Cusimano’s “Where I Started”; Clarke’s “Waiting for the Surgery” with Dr. Cusimano’s “Getting Ready” and so on.

Ok, let’s explore further. What is intriguing about the use of multiple narrators in the book is what is essential to understand about all medical narratives: That they are co-created stories by people with different points of view, or what narrative theorists would call unreliability. Let’s start with the first “axis of unreliability”: The Axis of Facts. How does In Two Voices illustrate the shared mimetic reality of its two characters, or doctors and patients in general?

Ms.Ahrens: The book is about the pathways of communication for doctors and patients alike. Usually, in both medical fiction and medical documentation, these are separate paths that are walked alone. But In Two Voices shows that this solitude no longer has to exist: Medical narratives can be a converging journey in which the patient and doctor walk together in a loving (human, but professional) relationship built on respect. By putting the voice of the doctor alongside that of the patient, the book closes the gap typically assumed between two forms of reality: on the one hand, the subjective pains and transformations of the patient, and on the other, the objective expertise and procedures of the doctor. Here, doctor and patient inhabit the same mimetic plane—one of uncertainty, preparation and the shared anxiety of doing well enough for each other.

So the story deals explicitly with how, along the Axis of Facts, seemingly unreliable narrators (e.g., doctors and patients) can co-construct a shared and equitable medical reality. Let’s turn next to the second way narrators can be unreliable: The Axis of Perception. How did Clarke or Cusimano’s different backgrounds, both professional and personal, shape their perception of their shared story?

Mr. Pederson: Their backstories vividly demonstrate the way their different forms of trauma shaped them before they encountered each other as patient and surgeon. As Clarke says early on, “Illness has always been a member of my family.” (Her first lesson in helping care for her ailing mother was learning “to put up with, to accept, to stand by.” In her fraught relationship with her mother and in the wake of her father’s sudden illness and recovery, Clarke identified the belief that made her ill-prepared for the possibility of being a patient: namely, the idea that “‘the good patient’ gets better,” that is, gets over their issue and moves on with life. Clarke finding herself in a position to have risky surgery puts this attitude to the test.

Ms. Ahrens: The critical moment at the beginning of Clarke’s story is her “shock” at the realization that she was a patient. The denial that followed her mixed with the urge to prove she was a “good patient” made for an intriguing, and often unheard, perspective. On the other end, Dr. Cusimano had to fight his uncertainties as well as time itself. And pressures that come with time when dealing with life and death decisions affect the perspectives of everyone involved (the patient, nurses, and administrators) and this pressure can cave in on the doctor and feed the fear inside of him/her.

So we have seen how the book deals with unreliability in terms of facts and perception. The final calculus of unreliability is the Axis of Storytelling: What audience values or ideologies make the story affirming or challenging? To turn this axis slightly on its head, let me ask you this: Could we recommend this book to readers who are already well-versed in the literature of medical narratives? What about a general audience?

Mr. Pederson: While the focus is clearly the story of how Clarke’s and Dr. Cusimano’s lives intersect and impact each other, it would have been interesting (though not absolutely essential) to see the ideas laid out in the Forward expounded upon in an appendix or epilogue. Case in point, in the Forward, Dr. Brian Goldman gestures toward the increasing integration of humanities in medical education:

Medical humanities is giving people who study and work inside the corridors of medicine an opportunity to express their thoughts and feelings beyond a sterile recitation of signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings.

In spite of this exposition, the book leaves aside areas of concern like the epistemological norms of narrative medicine as a discipline and steps to be taken in academic institutions that might allow medical humanities courses to be offered alongside traditional forms of medical knowledge. And while the narrative content of the book itself offers a vivid example of the co-creation of narrative between patient and doctor, it lacks the plurality of narratives (i.e., other doctor-patient stories) that might provide a broader perspective on what a narrative medical framework can consistently accomplish across contexts.

Ms. Ahrens: There is a certain feeling of empowerment a person feels when someone shares their journey of suffering. Through every (retrospectively added) ellipse on the page, every comma added for emphasis, and every descriptor used to accent a word, In Two Voices puts the roller coaster drama of a medical narrative (even one you know turns out all right) into your heart and mind. The reader sees the pain, shame and fear the two of them feel, but more importantly the reader understands how, on a deeper level, they relate through shared trauma and insecurity. This story creates an empathy for the patient and doctor as a singular narrative unit. Between every high and low of their email correspondence is a moment of pause that allows you to evaluate the deeper meaning of the story. There is a significant realization that they both—patient and doctor—had hopes and demons, and how those bear on the stakes and success of their story. In Two Voices shows the humanity often lacking in the medical field (a world ironically eclipsed by the inner workings of the human anatomy). This story touched, and changed both Clarke’s and Dr. Cusimano’s lives, and it can also touch and change the reader's.—Aaron McKain, Amanda Ahrens and Steven Pederson

Dr. Aaron McKain is the Director of English, Communication, and Digital Media at North Central University in Minneapolis, Minnesota and a scholar focused on narrative theory and public health.

Dr. Aaron McKain is the Director of English, Communication, and Digital Media at North Central

University and a scholar focused on narrative theory and public health.

Amanda Ahrens is an

undergraduate at North Central University, studying the use of narrative and art to facilitate understanding of medical narratives.

Steven Pederson is a curator-critic and the Director of Communications for the Institute for Aesthetic Advocacy, a Minneapolis-based arts collective focused on public health.

The IAA’s most recent exhibit on medical narrative “Contaminated,” which uses the methods outlined in this review as a mode of art curation, can be viewed at https://www.instituteforaestheticadvocacy.com/

Amanda Ahrens is an undergraduate at North Central University, studying the use of narrative and art to facilitate understanding of medical narratives.

Our methodology for taxonomizing medical narratives in terms of unreliability is based on the “Chicago School” model of rhetoric, primarily the work of James Phelan. For a detailed description of the method, including more thorough definitions of the “axis of unreliability” that follow, see “Somebody Telling Somebody Else: A Rhetorical Poetics of Narrative” (Columbus, OH: Ohio State Univ. Press, 2017).

Steven Pederson is a curator-critic and the Director of Communications for the Institute for Aesthetic Advocacy, a Minneapolis-based arts collective focused on public health. The IAA’s most recent exhibit on medical narrative “Contaminated,” which uses the methods outlined in this review as a mode of art curation, can be viewed at https://www.instituteforaestheticadvocacy.com/

For Pedersen and McKain’s use of unreliability and aesthetic enactment as a method for public health advocacy on narrative medicine, see “Aesthetics, Ethics, and Post-Digital Health Advocacy” in PostHuman: New Media Art 2020 (Seoul, South Korea: CICA Press, 2020).

Take Daily As Needed: A Novel in Stories by Kathryn Trueblood

Novelist Kathryn Trueblood. The author teaches at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington. Like her previous works The Baby Lottery and The Sperm Donor’s Daughter and Other Tales of Modern Family, feminist themes feature prominently in Take Daily as Needed, which highlights the politicized and gendered dimensions of caregiving. Photo by Suzanne Bair

Are we capable of loving and being loved, in sickness and in health? Writer Kathryn Trueblood poses this universal question to readers in her novel Take Daily As Needed (University of New Mexico Press, 2019). The novelist, who teaches at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington, uses a series of short stories to form her engaging narrative about Maeve Beaufort, a multitasker who struggles to care for her ailing parents and rebellious growing children, all while coping with her own demanding work schedule and crumbling marriage. A diagnosis of a Crohn’s disease complicates her life even further; yet Maeve, who has a dark sense of humor and steady resolve, navigates these daunting challenges like any one of us—imperfectly, and best as we can. That resolve, she reminds us, is in itself worth celebrating.

Part of what makes the novel so relatable is its honest portrayal of caregiving. While there may be a certain nobility involved with serving others, Maeve demonstrates there is nothing glamorous about its emotional toll. Although she is perceived by her parents as “the good child,” Maeve still feels inadequate and frustrated, even when dutifully going to lengths such as moving her mother into her house. She realizes she has no reprieve from this underlying current of tension in everyday life, where she must be “attuned to the brittle, vigilant to the tone of taking slight”—or in death, which is described by her mom as “...the final abandonment.” What we learn is this: Caregiving is not a singular interaction; it is an ongoing commitment to honor our loved ones, no matter how difficult times may be. As a young caregiver and previous disability support worker myself, this message resonated with me. Caregiving involves bearing witness to life.

In one rare moment following her father’s death, Maeve allows herself a moment of self-compassion.“I bow, understanding for the first time that no matter what messed-up things I do in my lifetime, no matter whose feelings I hurt in the long hurdle towards perceived happiness, what will count is the practice of good I undertook everyday, the small hope I carried into each exchange, the desire somewhere, in all of my failings, to have proved useful.” Here, Maeve acknowledges the conflicting feelings of love and pain that are only reconciled by her intentions to do good. Sometimes, that is enough.

As a parent, she similarly experiences this complicated dynamic with her two children—how, at the peak of our exasperation, we often only have our love to offer. After another visit to the psychiatrist about her young son’s ADHD, Maeve is so overwhelmed about the medicalization of his future that it is all she can do to reassure her son, if not herself. “‘Norman,’ I say, clasping his hands with my own to quiet them, ‘I love you.’ ‘I know,’ he says, looking intently into my brown eyes with his blue.”

Like Trueblood’s previous works The Baby Lottery and The Sperm Donor’s Daughter and Other Tales of Modern Family, feminist themes feature prominently in this novel, highlighting the politicized and gendered dimensions of caregiving. Maeve is conscious that her husband, Guy, is increasingly disappointed in her lack of domestic flair. Although he lauds gender equality, she is expected to take on extra child rearing and housekeeping duties and gets questioned for wanting to pursue further schooling to become a paralegal. This character dialogue reveals more than the dissolution of Maeve’s marriage. Indeed, it raises questions about whether modern society has kept pace with the needs of working mothers so they do not have to compromise their professional or intellectual pursuits.

Gender equality is a universal issue, and this novel shows it has further intergenerational implications. Maeve struggles to balance her own parental instincts while recognizing her daughter’s growing independence. In one instance, the past meets the present when Maeve’s own unresolved trauma leads her to cut a hiking trip short with her daughter after being spooked by male strangers. Although progress has been made with birth control policies and awareness about sexual assault, there continue to be perplexing modern challenges to navigate, such as digital harassment. Readers gain insight into the intertwining complexities both parents and children face making and unmaking mistakes together.

Take Daily As Needed may focus on caregiving and parenting, but its mature themes appeal to readers from any generation because ultimately, the novel is a meditation on relationships and the many ways they erode and sustain us, for better or for worse.—Brianna Cheng

Brianna Cheng is a graduate of McGill University, where she obtained her Master's of Science in Epidemiology. She also completed a Narrative Medicine Fellowship at Concordia University. Her work has appeared in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, CMAJ Blogs, and Families, Systems & Health. She currently serves as a section editor for the McGill Journal of Medicine. @withbrianna

Places I've Taken My Body by Molly McCully Brown

Places I’ve Taken My Body by Molly McCully Brown, comes out in May 2020. To pre-order a copy, click here.

Molly McCully Brown has cerebral palsy, “which is a little like a stroke that happens when you are born” as she has to explain nearly every day to someone, somewhere. In Places I’ve Taken My Body, a collection of personal essays and her third book, she reveals her incessant, conflicted relationship with the body that she has carried since birth through to maturity as an accomplished poet, author and professor at Kenyon College. Several of these essays have been published elsewhere, but as collected set they provide an overlapping, ongoing conversation between body and voice that invites us into the experience of living a life in which the body can never be taken for granted.

The seventeen essays in the collection contemplate daily life that demands she accept the limitations that her cerebral palsy dictates on her ability to walk and maintain balance. Her life has been broken into four distinct epochs defined by her broken body: the original body before medical interventions, the body after extensive spinal surgery as a child, the body that by revolted during puberty, and her now slowly aging body that she believes will never improve. Woven across recollections of these epochs are seminal life events, including the loss of her twin sister shortly after birth, surgeries and terrifying medical interventions of various types, new academic and professional opportunities, deaths of family members, successes and failures. These essays were clearly written independently as basic introductory and situational information is often reiterated, but together the quilting of the essays creates a rich, multidimensional discussion into the nature of embodiment of self, voice and passion filtered through her uncooperative physicality.

As she moves through her many travels fueled by an urge to challenge her body’s literal limits, she grapples with identity as defined by her disability. She lays bare her grief and rage with the injustice of it all. She cannot escape her body, and sometimes does not even know if she wants to, but yet... all life must be experienced through the discolored lens of her body defined by medical lexicon and the disability politics she wants to shed. She is hindered by “this sense that I have to pay so much attention to my body, the ground right in front of me.” (pg.18) The necessary hyper-focus on the body creates physical and emotional barriers that impair her ability to enjoy what she achieves. This grief weighs heavily over us as readers. We feel her frustration at being moored to the earth while she wants to float free.

Ms. Brown’s collection of essays is a deep and graceful contemplation of her ongoing search for a stable identity that is powerful and authentic. She has her broken body, “I have needed fixing from the moment I was born. I can feel myself falling apart.” (pg. 81), but desperately does not want this body to define her, all the while honestly acknowledging the myriad ways it does. Ms. Brown is generous and forgiving of those who initially see only her body, including those doctors and surgeons who treat her over the years, and hardest on herself for wanting to deny that body.

“…I put on a nice dress and went to a bar I don’t usually frequent, but that I knew was accessible. I parked my Segway against the back wall and chose a table close enough that I could see it, but far enough away that it wasn’t obviously mine. I sat in the semi-dark and drank a bourbon, and enjoyed the thought that, looking at me, nobody would know that sitting at the table right now I could be any pretty young woman with a book in a bar. For all they knew, I could go dance. I could get up and walk right out of there, painless and fluid and unremarkable. I wouldn’t need to field a single comment or question, or get a single sorry look.

This lasted a few minutes, and then I felt guilty as hell for trying to crawl out of my skin.” (pg.88)

The collection includes “Bent Body, Lamb,” which is an elegant description of the comfort she has found in Catholicism, despite the paradox of not being able to partake in the rituals of mass due to her physical limitations. She identifies with the broken figure of Christ on the cross which highlights the mutual necessity of body and self. This is the strongest free-standing piece of the collection, and was very well received when published in Image Journal for its unfiltered exposure of her confrontation with God at the injustice of her reality paired with a path forward to hope and resolution. She concludes quite beautifully with “I am fearfully and wonderfully made.” (pg. 45) Is this not what everyone searches, regardless of the packaging we carry?

While these essays were not necessarily intended for a healthcare readership, I will be recommending this as necessary reading for my trainees in Neurology from now on. The totality of the overlapping essays crossing time and space provide a moving and powerful narrative of the lived experience of a patient who always demands to be more than a patient. —Lara K. Ronan

Lara K. Ronan

Lara Ronan, MD is an Associate Professor of Neurology and Medicine at Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College and Vice-Chair for Education in the Department of Neurology at Dartmouth Hitchcock in Lebanon, NH. She directs the DH Neurology Residency Program and has research interests in the intersection between the Arts and Humanities and Medicine. She is currently completing the Columbia Narrative Medicine Certificate Program and writing about the effects of individual narratives on the telling of the legacy of a single story.

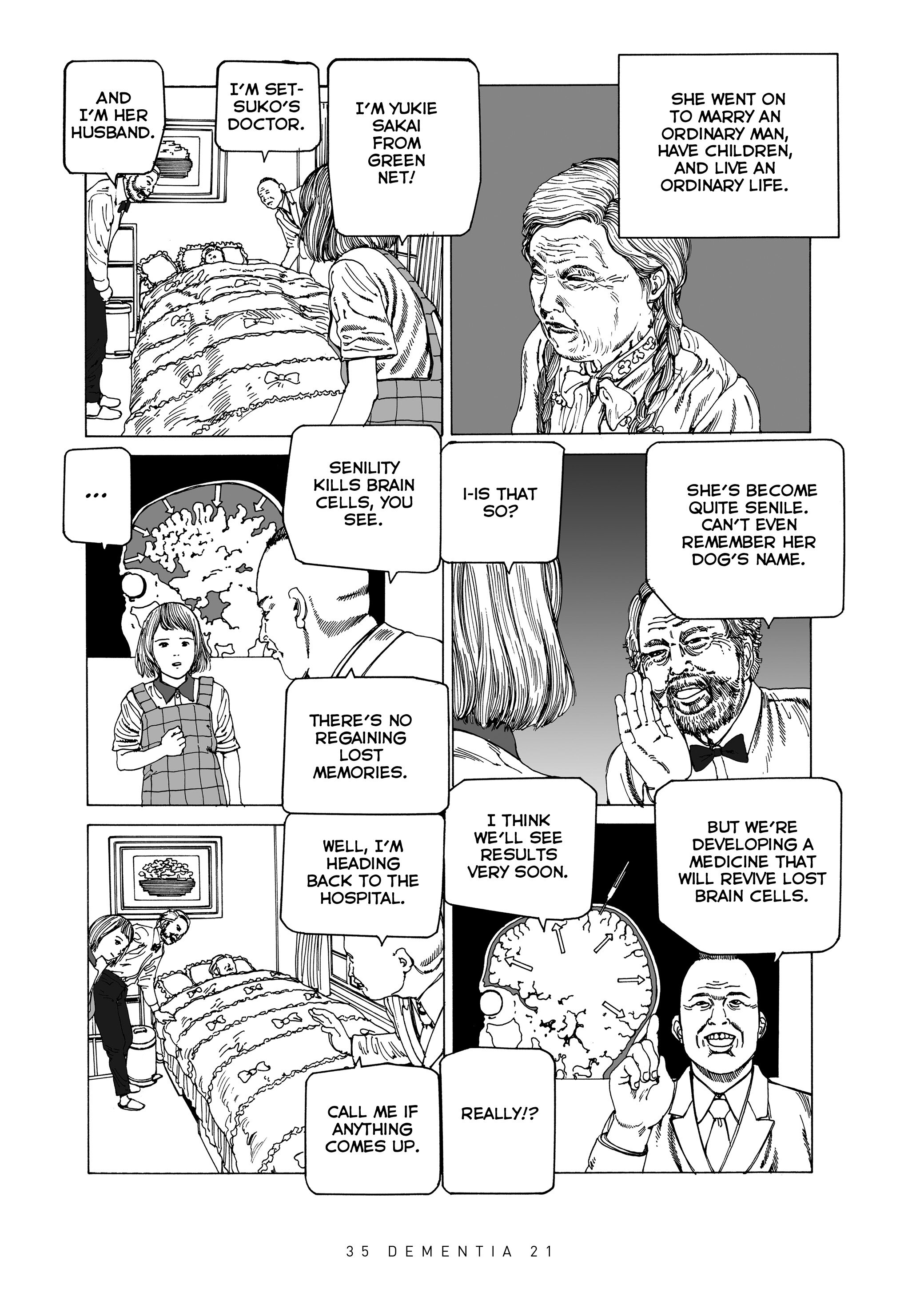

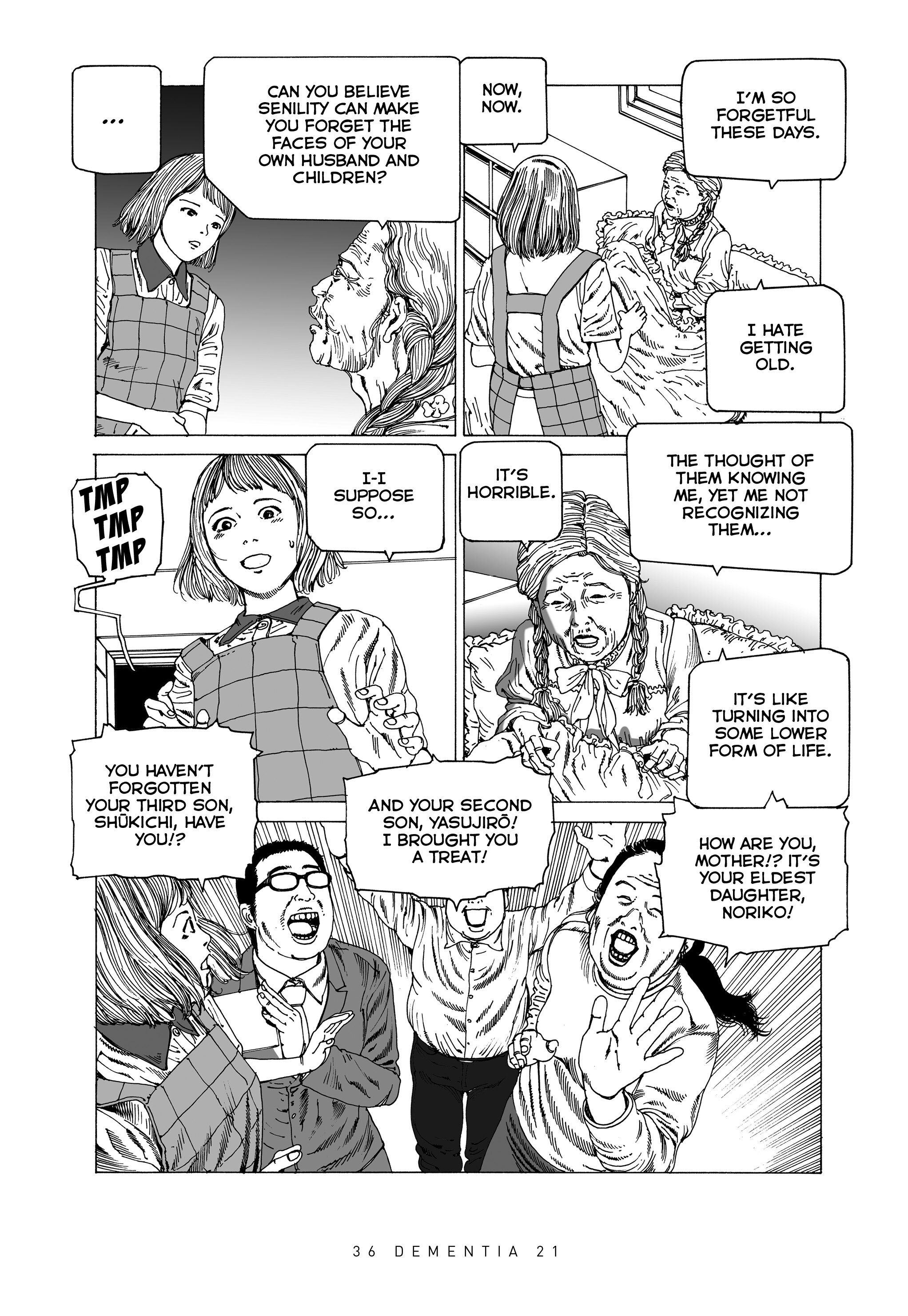

Dementia 21 by Shintaro Kago

Dementia 21 is a horror graphic narrative by Shintaro Kago, published by Fantagraphics Books

Dementia 21 is twisted. I mean that in the best possible way.

From the eerie, delicious mind of Shintaro Kago, the Japanese ero guro nansensu (horror mixed with surrealism) manga artist, Dementia 21 is a chronicle of surreal stories about Yukie Sakai, a home health aide. The horror graphic narrative is twisted and destabilizing, with characters who transform throughout the story, revealing different sides. What you expect is never what the story—or characters—turn out to be, and that is the beauty of what Intima sees as a graphic medicine classic, the first of several translations of Kago’s work that Seattle-based publishing company Fantagraphics Books will release.

Kago’s stories in the volume follow the hardworking Yukie through days fraught with unexpected drama from her patients, their family members and others (see below for a short example). She tries to handle them as they come at her, and she usually can cope with the weirdest situations. But as fellow home health aides become jealous of Yukie’s ability to get the top score at the company each month, a rival healthcare worker plots to send her to difficult clients to drop her score. The first home Yukie gets sent to turns out to be a death trap, where five previous home health aides have met strange and freak accidents. While cleaning, Yukie comes across a secret panel depicting the faces of the five previous aides when suddenly, the elderly patient Yukie is helping attacks her. Yukie survives, however, because the old woman needs her heart medication, and ironically, in exchange for the medication, Yukie gets a high score.

The contest for top home health aide quickly devolves into the absurd. The second home Yukie is sent to has three elderly women. Caring for three people is already exhausting enough when the next day, those three women become six. The next day, six become twelve, until the whole house is crammed with elders. Strangers dump their relatives at the house, and Yukie is appalled. “How can you let yourselves be treated this way?” she cries to the patients. “Thrown out like trash by your own flesh and blood! DOESN’T THIS BOTHER YOU AT ALL!?.” It’s a question they are powerless to answer.

Every chapter begins with a full-page spread, one of this graphic artist’s signature techniques. Sometimes Yukie is crawling out of her own face; sometimes she is fending off danger, hair flying; sometimes she is being strangled and swallowed by wires. Often, the backgrounds of panels convey horror, fear, and confusion with layered visual elements—brush strokes, whorls, gothic detailing—that portray a chaotic emotional reality. These graphic strokes reverberate and tantalize the reader but also create a sense of horror about the confusion of health, illness and difficulties of healing and healthcare.

This powerful narrative contains multiple meaning: Part social commentary and satire, part menacing story colored by greed and selfishness, part narrative on thankless work, Dementia 21 is a transgressive form of graphic medicine. When I read other memoirs on aging and dementia, such as Joyce Farmer’s Special Exits and Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, I sense fear and anxiety, trembling and loss. When I read Kago’s book, however, it’s a different energy: one tinged with madness and imagination. It reads like a dream: What should we believe? What should we hold onto? What parts strike us most, and what does that say about us?

Dementia 21 is the myth of Sisyphus through a Japanese lens, with an enthusiastic healthcare worker tirelessly pushing against obstacles to make a difference while also making a living. At its core, the book is a graphical exploration of dementia and aging and its accompanying themes of abandonment, forgetfulness, senility, competition, technology, division and difference, abuse, and bullying. Ultimately, it is an eye-popping and painful story that explores the meaningfulness of life by focusing on the elderly and those who care for them.

Over thirty years since he debuted his first book, Comic Box, Kago continues to cross boundaries most other manga artists won’t go near by subverting expectations and breaking the fourth wall. His aesthetic is akin to shifting on soft soil, wallowing in shit (literally), its narrative dark but laugh-out-loud funny. He forces you to push your boundaries to the point of discomfort, and challenges you to stay there.

Dementia 21, Vol. 2 is scheduled for release in early 2020.—Jane Zhao

Jane Zhao

Jane Zhao is a lover of comics because when she has no brain or patience for words, she can escape into image. She is a graduate of the Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University and studied neuroscience at McGill University. She currently works in research in Canada. Talk to her about poetry, Donna Haraway, health policy, and muscle pain.

Crossing Paths by Paolo Montalto, MD

"Organ transplantation always results in a crossing of paths: there is a life that ends and another that regains vital energy: hours of anguish and despair on the one hand, of apprehension and joy on the other. A cruel but inevitable crossing." These are the words of Dr. Paolo Montalto, a gastroenterologist who graduated from the University of Florence's Medical School after studying at the Hepatobiliary Unit of the Free Hospital in London.

Read more