For the third time in as many weeks I’m reading Cortney Davis’s Taking Care of Time. I’m constantly jotting notes and underlining words, for every poem has a line I want to remember. I am grateful to the nurse Davis is and in awe of the nurse writer she has become. She sees under the skin of our lives, accepts and captures us in her poetry.

The first section takes Davis from practicing student to practitioner: I stabbed oranges until my hands ran with juice, then the patients until my hands ran with grace. Quickly she learns what nurses signify when we are outside of our hospital clinic setting — in the physicality of touch and embrace — but it is early in her surgical rotation where she prays as she recognizes her calling: Let this be, let this be, my life’s work.

In “Stoned,” she learns to distinguish the smell of death, unraveling it from under the smell of marijuana and hospital rooms. Driving home, a radio update on the weather takes her thoughts to the rise and fall of the body’s temperature until she collects herself — the weather — she says out loud — - the weather. That’s all.

It may be in the woman’s clinic where Davis truly loses her heart, as she receives her young patients. She sees beyond the narrow mouth of a vaginal speculum and the reach of her hands cupping a budding uterus, while hearing the nervous words and beating hearts of her young patients, who come to her with their anxious mothers hovering beside them and the fluttering hearts of their unborn babes to the fears they carry:

I reach up, enfold her hands.

I too had to learn that my body was mine.

And then a sharp one-movement poem, as Davis becomes the patient. Now Davis learns another level of loving. In her deepest pain, she understands gender:

How necessary both -

The tender gentle sympathy

and at other times

The strength and deference

that lifted and held and did not let me fall.

We witness the beloved care of the nurses, in juxtaposition to the teaching residents, each one smacking the hand sanitation device, as they abandon her.

I’m not sure Davis learns to overcome the fears she finds in her patients. But it is in her poetry that she can comfort them, herself and us. In “On Call: Splenectomy,” she writes:

I’ve taken Pity on you

left out the really awful part . . .

And these stories

How I tame them on the page.

These are Davis’s gifts, the stories that she has plucked from her life’s work. Now, in these terrible frightening times, we draw comfort from Davis’s poems, knowing she has received us. She has heard our stories and our cries, returned them to us, wrapping her words to in poems.

Here they belong to you, she seems to say. We receive them with gratitude.—Muriel A. Murch

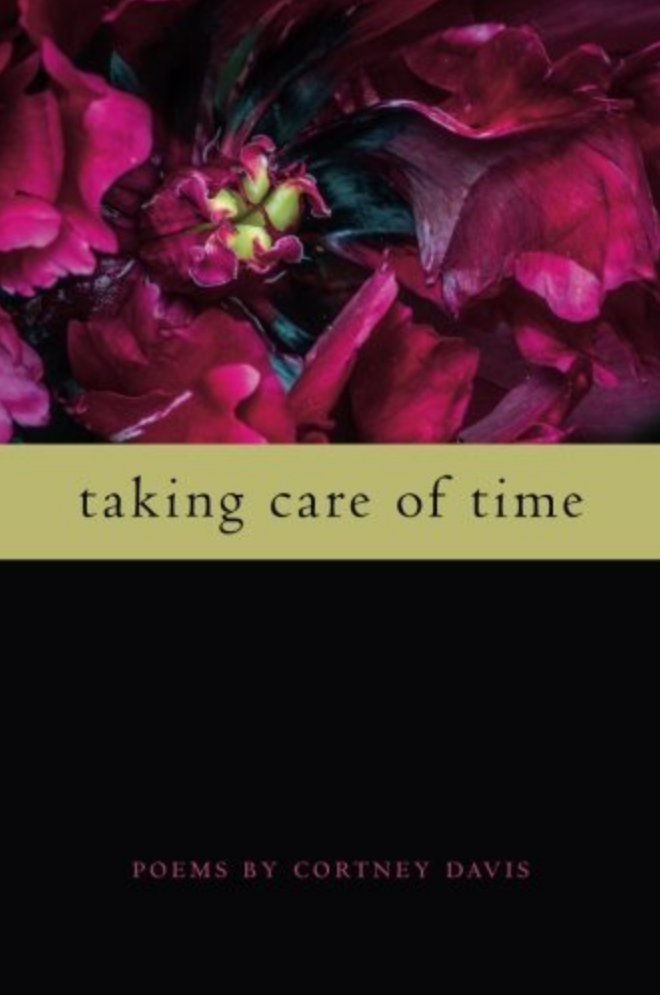

Cortney Davis, a nurse practitioner, is the author of Taking Care of Time, winner of the Wheelbarrow Poetry Prize (Michigan State University Press, 2018). Her poems "Entering the Sick Room" and "It Was the Second Patient of the Day,"appear in the Fall 2018 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine. Learn more about her work at cortneydavis.com

Photo by Jon Gordon.

Muriel A. Murch was born and grew up England, graduating as a nurse in 1964. In 1965 she married Walter Murch in New York City, and they motorcycled to Los Angeles, relocating to the Bay Area in 1968. Murch has a BSN from San Francisco State in 1991, completing her book, Journey in the Middle of the Road, One Woman's Journey through a Mid-Life Education (Sybil Press 1995). Her short stories and poetry are included in several journals, including most recently, Stories of Illness and Healing, Women Write Their Bodies (Kent State University Press 2007); The Bell Lap Stories for Compassionate Nursing Care (CRC press, Taylor and Francis 2016); and This Blessed Field: How Nursing School Shaped Our Lives and Careers (Kent State University Press 2018). Her work is included in the anthology Learning to Heal, Reflections on Nursing School (Kent State University 2018). Discover more about her work at murielmurch.com.