In the hospital, routines carry us through our days and lend a semblance of structure to the chaos of lives disrupted by illness. Some routines happen on a large scale—weekly gatherings of departments for Grand Rounds, hospital leadership meetings for safety huddles, the hustle of getting a cadre of operating rooms started nearly simultaneously in the predawn. Other routines are more intimate—the sequenced process of doing a sterile central line dressing change, the donning and doffing of PPE outside a patient’s room, the one-one-one nursing handoff at shift change.

Read moreWhen Medical Professionals Care for Their Own: A Response to “Of Prematurity and Parental Leave,” by Mason Vierra

“Of Prematurity and Parental Leave” (Intima, Fall 2021) describes the harrowing experience of giving birth to a premature baby during residency. It’s written by doctors married to each other —Dr. Campagnaro and Dr. Woodside—who co-construct a narrative by telling it from their own perspective.

Read moreStill We Dream: How We Face the Unpredictable World by Mary Anne Moisan

Humans can create a world through perception, imagine a potential life, whether it be the life of a relationship or the life of a baby. We fill in the unknown details to make a whole that is pleasing and good. It’s as if we willfully ignore that so much of life is unpredictable.

Read moreA Simple Ritual: Reflecting on the Moments Before Surgery by poet and orthopedic surgeon Photine Liakos

Surgeons are well-known for precision and protocols. There is often a ritual nature to our actions when preparing for surgical interventions, an orderliness and discipline: checklists, time-outs, pauses, consensus.

Read moreThe Shit Poems: A Reflection by Drea Burbank

I am interested in the juxtaposition between my use of poetry to shed traumatic experiences and memories from medicine, and the description of William Carlos Williams by Britta Gustavson (“Re-embodying Medicine: William Carlos Williams and the Ethics of Attention,” Spring 2020 Intima).

Read moreThe Limits of Love: A Reflection by Carmela McIntire about Anorexia, Overeating and Fulfillment

Disordered eating occupies a spectrum—anorexia nervosa at one end, morbid obesity at the other. Attempting rigid control of the body and its appetites, anorexics are unable to see themselves and their bodies accurately. Compulsive overeaters—often obese—similarly might not see themselves accurately. In both disorders, controlling food is the aim, a genuine addiction, a strategy through which addicts deal with the world and their own circumstances—a necessary coping skill, even though it is risky to health in both cases.

Read moreMothers and Daughters: A Reflection on Cancer, Caring and Seeing the Whole Picture by poet Kathryn Paul

—After ‘Macroscopic” by Adela Wu (Spring 2021 Intima)

My mother and I were not close. I knew she wanted us to be, but I couldn’t do it her way. For most of my adult life, I kept my distance, emotionally and physically. We lived on opposite sides of the continent. In her 80’s, the creeping dementia my mother never discussed was overtaken by a cruel and much more terrifying diagnosis: Stage IV ovarian cancer.

Aided by her cancer-free twin sister, Mom endured multiple surgeries and two lengthy and debilitating rounds of chemo. Each time, her cancer came roaring back within weeks. Her surgeon suggested an experimental Round Three. Mercifully, her oncologist suggested hospice at home instead.

During the first year of Mom’s illness, I was trapped by my own cancer treatment, unable to participate in her care. I called daily, spoke with her, spoke with my aunt, asked about her pain, her “tummy trouble,” her ascites, and her white count. I took notes and dictated the questions to ask at her next appointment.

As soon as my doctors cleared me to visit her, I did. I was always on the verge of moving in with her, but never quite needed to do so. I flew back and forth. The more debilitated she became—by her cancer and her dementia—the more often I visited.

Adela Wu’s Studio Art piece “Macroscopic” simply and eloquently captures the changes in how I experienced my mother during those last months and weeks. The simplest things gave her joy: A small dish of ice cream. A pain-free nap on the down-stuffed cushions of her couch. Cuddles with her cats. A bird visiting the feeder outside her window.

Even as her disease spread through her body, even as she faded, my mom seemed to crystallize. She became, ultimately, the Essence of herself. And—just at the end—I finally saw her.

Kathryn Paul

Photo by Andrew Givhan

Kathryn Paul (Kathy) is a survivor of many things, including cancer and downsizing. Her poems have appeared in Rogue Agent, Hospital Drive, The Ekphrastic Review, Lunch Ticket, Stirring: A Literary Collection, Pictures of Poets and Poets Unite! The LiTFUSE @10 Anthology. Her poem “Dementia Waltz” appears in the Spring 2021 Intima.

Shakespeare, Stanzas and How We Think About Death by Albert Howard Carter, III, PhD

When my sonnet “All Tuned Up” appeared (Spring 2021 Intima), I was asked to write about another piece published in the journal. I chose “I Picture You Here, But You’re There” (Spring 2020 Intima) by Delilah Leibowitz. Her poem and mine both explore how we think and feel about death.

Read moreHow Touch Affects Healing, a reflection by Wendy Tong

In her Field Notes essay “Hand Holding” (Fall 2019 Intima), Dr. Amanda Swain describes the experience of beginning her surgery rotation as a third year medical student. In the early days of the rotation, she feels an intense sense of being out of place within the “intricately choreographed dance” of the operating room. But when the next patient is wheeled in, Dr. Swain is reminded of how a nurse once took her hand before she underwent surgery, the touch conveying an unforgettable message of comfort during a time of deep vulnerability.

Read moreOn Fathers, Love and “Exit Wounds” by psychiatrist and essayist Greg Mahr

I regularly attend a poetry critique group in Ann Arbor, MI called the Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle, named after the bookstore and tea shop where we used to meet before the pandemic. The experienced poets there have come to accept the sad and overly personal poems and flash pieces I write and help me craft them into something that sometimes almost sounds like real writing. One of them once told me, “You always write from a place of longing. That’s a good place to write from.” I realized he was right. I find it hard to share what I write with the people I love. When I am in a good relationship, I write about bad ones; when I love someone, I write about missing them.

Read moreAuscultating Meaning: Reflections on the Heart of Medicine by Marc Perlman

© Gordian Knot by Elisabeth Preston-Hsu Spring 2020 Intima A Journal of Narrative Medicine

From diaphragm to earpiece, a stethoscope dutifully chaperones a patient’s internal orchestra to a clinician’s ears. This facile acoustic communication not only allows a provider to screen for a wide host of cardiovascular, pulmonary and gastrointestinal anomalies, but it also may be a conduit for moral reflection.

Read moreDoctoring and Disobedience: Speaking an Important Truth, a reflection by Kelly Elterman

Sometimes, the truth can be uncomfortable. It can be difficult to hear and often, even more difficult to say. In her Field Notes piece entitled “Doctoring and Disobedience” (Spring 2020 Intima) Dr. Lisa Jacobs recalls her struggle with being told to hide the truth of a prognosis from an elderly patient with metastatic disease. Despite the instruction of her attending physician, and the decision of the patient’s family and ethics team to not speak of death to the patient, Dr. Jacobs feels compelled to let her cognitively-intact patient learn the truth. So strong is her conviction that she takes on considerable risk to her own career for the sake of bringing the truth to her patient.

Read moreHealing and Trauma: Recontextualizing Suffering by Sundara Raj Sreenath

Suffering due to trauma or illness often brings with it feelings of disconnect from the world as we knew it when we were healthy. The healthcare provider-healer, therefore, has an important opportunity to intervene in this unique setting and respond to the patient’s cry for help by offering a personal, humanistic touch and guiding them through trauma in addition to clinical management.

Read moreReimagining Chaos in Art and Poetry by Selene Frost

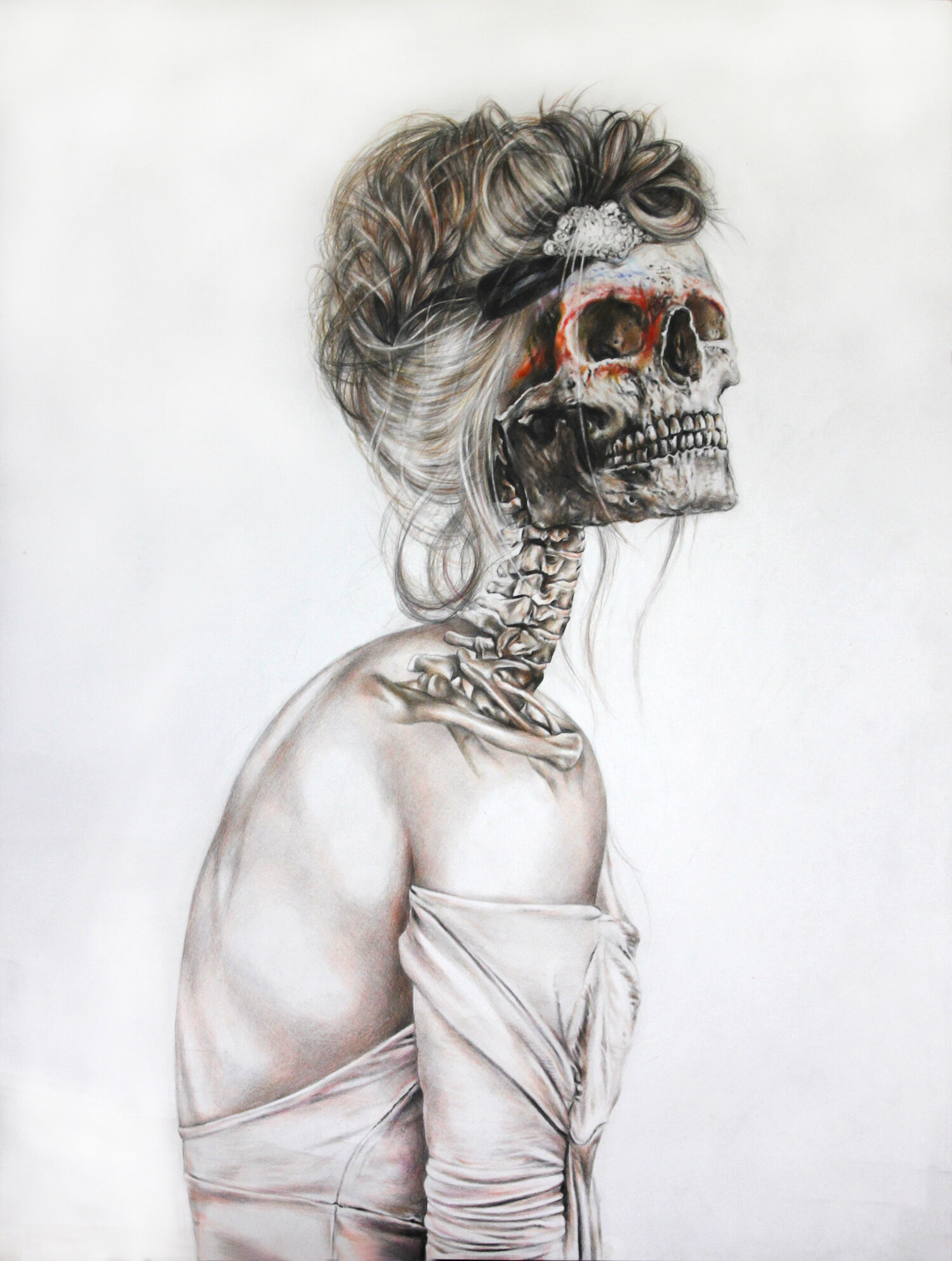

Anatomy of the Vogue by Meagan Wu. Fall 2017 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine

I’ve long been fascinated by the way structure informs poetics and the practice (and in this case—reception of medical care). In my piece “Field Notes on Form,” I extol the ways in which linguistic structure has the remarkable ability to organize our thoughts, increase our signal within the noise, and etherealize the mundane. In “Post NICU Villanelle,” Joyelle McSweeney uses language not only to remediate the chaos of loss and of leaving but also to deconstruct both the poetic form and herself.

Read moreThe Cost of Efficiency and the Price of Empathy, a Reflection by Jordana Kritzer MD

After the long hours and intense learning curve of my Emergency Medicine residency, I had become one of those efficient robots who could solve medical puzzles and save lives, but I felt empty, disconnected—the classic symptoms of burn-out. I was once a wide-eyed, empathetic intern constantly criticized for trying to solve their patient’s chronic issues. I remember one attending saying, “Figure out the least amount of things you need to do to rule out an emergency.” I see now that he was trying to teach me efficiency.

Read moreLife in the Gaps: How Illness Transforms Our Sense of Time by Renata Louwers

It was in those gaps, between our lived experience—the crushing uncertainty about how long my husband would live, the daily reality of his intolerable pain, and the abrupt shift from a life of joyful ease to one spent contemplating death—and the oncology profession’s standards of care, first-line treatments, and numeric pain scales that my frustration festered.

Read moreBecoming the Superheroes Our Parents Need: The Journey from Child to Worthy Caretaker by Usman Hameedi

Our parents are often our first examples of superheroes. They make gourmet meals from minimum wage, give hugs that vanquish our demons, and provide limitless love. They are impervious to damage or decay and are always ready to save our days. So, seeing the human in them, the mortality in their breath is unsettling. When they come to need us, we feel so grossly unprepared.

Read moreAnatomy Lesson: See the Face of Those Before You by Rodolfo Villarreal-Calderon, MD

For those with the privilege of having participated in a longitudinal cadaver dissection, the connection you build with the donor’s body is known to be a truly unique experience. That bond is part of what I attempted to capture in my poem “Through Damp Muslin.” Especially reflecting on how to express gratitude to the person who once was—and now who is, or at least whose body is—lying before you.

Lady Psychiatrist Queen: Compassion in Caregiving, a reflection by Eileen Vorbach Collins

Lisa Jacobs, in her nonfiction piece, March Manic (Intima Spring 2019) describes a long shift on a psychiatric unit. She is “beyond exhausted” to the point of having questioned her own grasp on reality.

As a case manager in a Baltimore City hospital, I once spent hours attempting to find placement for a homeless 19-year-old addicted to heroin who needed long term IV antibiotics. When I asked if I might call her mother she replied “I don’t give a fuck” but retracted her permission as I was leaving the room. I pretended not to hear. The next day I was told she had signed out AMA (Against Medical Advice). a colleague said, “Get over it. She was a waste of time and resources.”

Read moreWhat Does ‘Paying Attention’ Mean in a Healthcare Setting? A Reflection by Ewan Bowlby

Ewan Bowlby is a doctoral student at the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts (ITIA) in St Andrews. He is researching ways of using mass-media artworks to design new arts-based interventions providing emotional, psychological and spiritual care for cancer patients. Bowlby’s paper “Talk to me like I was a person you loved”: Including Patients’ Perspectives in Cinemeducation” appears in the Spring 2021 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.

Narrative Medicine is about creating connections: finding words, ideas or stories that bridge the gap between patients and health professionals. This search for common ground is beautifully rendered in Carol Scott-Conner’s short story “Christmas Rose” (Spring 2017 Intima). Her fictional narrative reveals how mutual understanding can emerge in unexpected places. An encounter between the resolute, inscrutable Mrs. Helversen and her oncologist shows that the relationship between a physician and patient can flourish when the physician pays attention to the intimate, personal details of a patient’s story.

Initially, the clinical encounter in “Christmas Rose” seems unpromising, hampered by reticence and disagreement. Mrs. Helversen, who has a neglected tumor on her breast, has been “strong-armed” into a cancer clinic by her concerned daughter, and she is not receptive to the prospect of treatment. Scott-Conner, a Professor Emeritus of Surgery at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, switches the first-person narrative from Mrs. Helversen to her oncologist, allowing the reader to inhabit two alternative perspectives on the same meeting and reminding us that the same interaction can be interpreted very differently.

When I wrote an academic article that appears in the Spring 2021 Intima proposing that patients’ perspectives should be included in “cinemeducation,” these differences in interpretation were central to my argument. Showing clips from films to encourage medical students to relate to a fictional patient is an excellent idea. Yet listening to how patients respond to these clips can enrich this pedagogical method. As I demonstrate through the qualitative research presented in my article, patients “see things differently.” The same fictional scene featuring a patient-doctor interaction can draw responses from patients that surprise and challenge healthcare professionals. So, why not use such scenes as a space in which different perspectives can be expressed and discussed, bringing patients and providers together through the audio-visual medium?

In “Christmas Rose,” it is a rock that facilitates this meeting of minds. While the oncologist is surprised when Mrs. Helversen describes her tumor as a “rose,” betraying a complex emotional attachment to the growth, she finds a way to react empathetically and imaginatively to Mrs. Helversen’s unusual behavior. Offering the elderly patient a desert rose rock in exchange for her tumorous “rose,” the oncologist persuades Mrs. Helversen to accept treatment. This fictional oncologist shows an adaptability and ingenuity that the health professionals involved in my research also exhibited. In my article, I describe how health professionals engaged constructively with patient’s unique or unexpected responses to imagined patient-doctor interactions in films. Listening to both sides and hearing alternative perspectives on the same encounter can yield important, enlightening insights, whether one is participating in a focus group, watching film clips or doing a close reading of a short story such as “Christmas Rose.”

Ewan Bowlby is a doctoral student at the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts (ITIA) in St Andrews. He is researching ways of using mass-media artworks to design new arts-based interventions providing emotional, psychological and spiritual care for cancer patients. This involves using fictional narratives, characters, and imagery to reflect and reframe patients' experiences of living with cancer, helping them to understand and articulate the effect of cancer on their lives. He is developing the impact of his research through an ongoing collaboration with Maggie Jencks Cancer Care Trust (Maggie's) and Northumberland Cancer Support Group (NCSG). Other interests include theological engagement with popular culture, the relationship between theology and humor and the use of narrative form for theological expression. Bowlby’s paper “Talk to me like I was a person you loved”: Including Patients’ Perspectives in Cinemeducation” appears in the Spring 2021 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.