A retired gynecologic oncologist reflects on her own career and realizes how watercolor artwork can allow for even healthcare providers to be seen.

Read moreWisdom of the Ages: A Surgeon's Reflections on Writing, Vocation and Satisfying Endings

As I was creating Hal Winters, the character at the center of my short story, “Old Scrubs,” (Spring 2024 Intima) I imagined a rumpled, gray-haired, and unflappable older male surgeon who has seen it all. He heads to the hospital every day, goes through the motions and gets his work done without fanfare or fireworks. He hasn’t felt the spark of “why” he went into medicine for years but, as long as he remembers the “how,” he will keep plowing the same furrow.

Read moreBefore and After: In Response to “The Face as an Organ of Identity” by California community doctor Katie Taylor

I work at a community clinic with patients who are homeless–there is the stigma of homelessness, and then there is the stigma of looking homeless.

Some patients of mine do not–or do not yet– appear unhoused. It is usually those who still have family that support them, who live in a car, who hold a job—running food for Doordash, picking for Amazon, sitting security—or who have not been homeless for so very long. But many of my patients do appear frankly homeless: a shuffling gait, a blanket draped around their shoulders, belongings pushed in a stroller, blackened teeth, leg wounds.

Leaning Close: "No more interventions. No more transfusions." A reflection on mortality and morbidity rounds by pediatrician-writer Laura Johnsrude

When I read “All Tuned Up” by Albert Howard Carter III (Spring 2021 Intima), I remembered a pediatric intensive care unit patient from my own 1980’s residency experience. In Carter’s poem, a medical resident presents a case during mortality and morbidity rounds. The resident is moved to tears as he tells the gathered audience about the death of a patient he knew well. A senior doctor “gently” offers context and says, “Maybe he was just tired.”

Mercifully, I’ve muffled memories from some of the deaths during my residency training in the pediatric intensive care unit. But I remember a slight girl of about sixteen with silky, wavy hair, lying in a metal-frame bed parallel to the wall against the window, in silhouette.

Read moreThe Healing Power of Empathy: Does it Exist? Can it be Acquired?

In this reflection, a retired surgeon examines the research findings of evidence-based medicine to uncover whether empathy, in addition to the principles and practice of narrative medicine, can facilitate deeper healing.

Read moreFear and Compassion: At the Heart of Panic Attacks by Lisa H.D. Napolitan

© How a Heart Grows. Susan Baller-Shepard. Fall 2018 Intima

Fiction and visual art are a natural pairing, one digging deep through words, the other a profound visual exploration. Both genres allow ways to explore the issue of mental health.

Read moreHow to Write About Cancer: How Poetry Can Break the Rules by writer Lynne Byler

Recently, I read Adam Conner’s short story “How to Write about Your Cancer” (Fall 2022 Intima) with amusement and recognition. And if I transform the rules in it to a scorecard, my poem, “Minds Go Where Bodies Can't” ends in the red.

Read moreListening to Beethoven: A Reflection on Professional Responsibility and Personal Recognition by poet Susan Carlson

“I like Beethoven the best!” is a declaration made by a patient of Mitali Chaudhary, as she readies to leave his hospital room. A busy senior medical resident at the University of Toronto, Chaudhary juggles many demanding responsibilities with her desire to get to know this elderly patient. In her Field Notes essay titled “Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5,” published in Intima’s Fall 2023 issue, she recalls how she’d tried to get her patient to respond to questions about symptomatology, all the while aware that twenty-three other patients – along with a group of junior residents and medical students – were awaiting her time and attention. In that moment, she finds herself turning away from an opportunity for a personal interaction with him in order to ensure she manages her tasks appropriately.

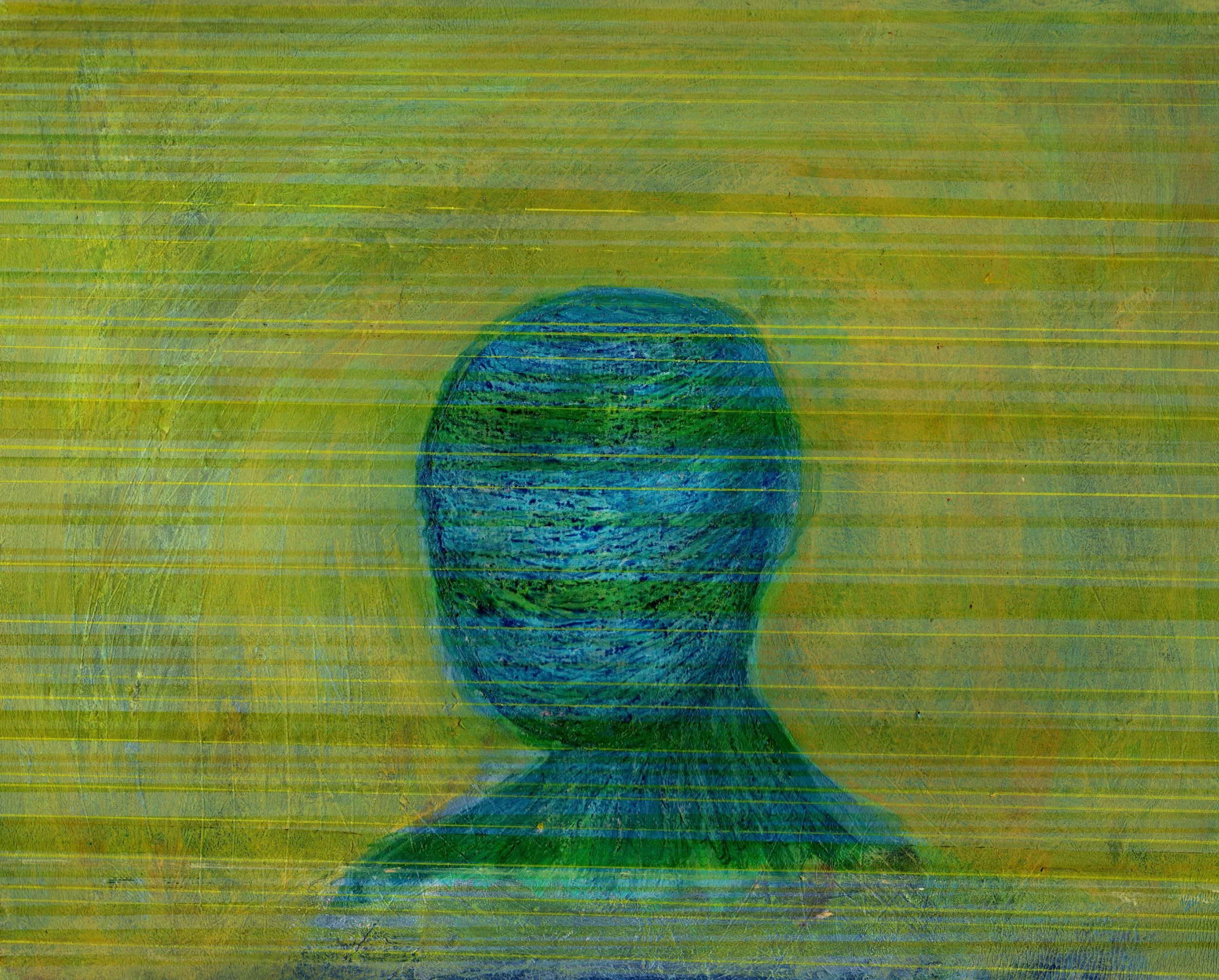

Read moreDementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: When the Outside Looks Different From What’s Happening Inside by Kimberly Mitchell

© The War Outside. From “The Impact of War on Mental Health” series. Claire Lawrence Spring 2022 Intima

One of my most enduring memories of volunteering is of helping with a beauty club for patients with advanced Alzheimer’s Disease. Each week I would be regaled with stories of young women visiting their mothers and planning fun outings with their girlfriends. While I applied makeup and painted fingernails, the smiles and facial expressions were those of young women anticipating a good time.

On the outside these ladies were quite different.

Endurance and Gratitude: A reflection on finding joy in difficult moments by Laura Carmen Arena

Both Karen George’s poem, and my “Triptych:Oncology Fish,” share an expression of admiration for the resplendent inner strength in our loved ones, emanating despite the foreboding shadows of illness, suffering and loss. The emotions floating around our lived spaces as our loved ones endure and battle disease in the face of difficult circumstances move in many directions including grieving, reflecting, hoping, enduring and celebrating, colors that shift and radiate with the heroically hopeful, illuminating presence of gratitude and love.

Read more"Reading" Patients When Illiteracy is What Afflicts Them: A reflection by medical oncologist Jose Bufill

While returning to the U.S. on an international flight not long ago, I sat next to a young African woman. As we approached our destination, she sheepishly passed me her passport and a customs form. Since I was in the aisle seat, I assumed she wanted me to pass it along to the flight attendant, until I realized the form was blank. She was asking me to fill it out.

Read moreWhat Great Literature Taught Me by internal medicine resident Teva Brender

Great books can guide us in every day life, and I found it fitting that Dean Schillinger, MD and I both invoke works of literature to describe the experience of realigning our values with those of our patients. In his essay, “The Quixotic Pursuit of Quality,” (Spring 2015 Intima) Dr. Schillinger compares himself and his patient, Mr. Q, to Quixote and Sancho Panzo from Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s Don Quixote. With only misplaced medication lists, no-show appointments, and a stubbornly elevated hemoglobin A1c to show for his repeated efforts to help Mr. Q better manage his many comorbidities, Dr. Schillinger’s frustration melts away when Mr. Q unexpectedly gives him a massage. From then on, “the duel was over.” There would be no more tilting at windmills.

Read moreThe Thing About ‘Good News’ at the Doctor’s Office by neuropsychology postdoc fellow Sarajane Rodgers

In theory, whenever we go to the doctor, most of us want to hear “good news.” The test is negative. You don’t have ___. Your results are inconsistent with ___. There are times where we take that in and walk away with an emotional weight removed. Other times, we are left with a void. The diagnosis we thought we could hang a hat on is taken away. Now where do we put our hat?

Read moreOn Subtraction: Understanding What's Lost and Gained in Clinical Encounters by Abby Wheeler

I recognized right away a kinship with Bessie Liu’s “Variations on the Negative Space Before Healing” (Fall 2023) and its use of subtraction to create new meaning; The poem by Liu, a third-year medical student at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. very much feels like a sister to my poem, At the Doctor’s Office, I Check, Yes, I Have Experienced the Following: Sudden Weight Loss (Fall 2023).

Read moreWhat Clown Doctors See and Don't See: A Look at Healthy Humor by Phyllis Capello

Phyllis Capello, who is a writer and musician, is a NYFA fellow in fiction I and a winner of an Allen Ginsberg Poetry Award. Her collection “Packs Small Plays Big” is from Bordighera Press, 2018. Cantastoria work (sing/storyteller) has taken her from Ireland-to-Istanbul. She has presented at the International Oral History Conference in Rome, Italy and has been a musician/clown since 1990 with Healthy Humor Red Nose Docs, as well as a member of the poetry/activist trio, The Ferlinghetti Girls. ferlinghettigirls.com In 2023 she was honored with People’s Hall of Fame Award for teaching artistry for her work in New York City schools. Her poem “The Ballad of a Harlem Boy” appears in the Fall 2023 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.

For thirty years, my hospital work (I’m a clown ‘doctor’/musician for Healthy Humor) has included meeting and entertaining families in clinic waiting rooms, Pediatric ICUs, triaged Emergency Departments and in out-patient, in-patient rooms. Clown-doctor encounters can, if invited, also extend to physical therapy and treatment rooms, hallways, nurses’ stations and elevators. In ED and in out-patient and in-patient rooms permission comes from the medical and childlife staff first (and pertains to situational or isolation status). After that, the child’s permission (being our ultimate “boss”) to enter is strictly respected. In a hospital environment, we are one thing a child can prevent from entering their room.

Knowing when to present ourselves and when to exit means we are not often present for the trauma of Emergency Medical procedures unless specifically requested by staff. I do not see the immediate medical aftermath of a bullet wound. The hands of professionals as they seek to save a life as in Kirilee West’s drawing of hands entitled: “6:21 P.M.” That is why the piece really speaks to me of the drama and humanity inherent in the moments before a medical clown can be of any use to a patient.

Her drawing resonates with me as my poem, “The Ballad of a Harlem Boy,” was written after a nurse shared her distress about a child’s death. Telling us (we work in pairs) of her direct experience, I could only think of her hands and their expert ministrations during that terrible time and of the depth of her humanity for the mortally-wounded fourteen-year-old and his mother.

We all want our hands to be of use: I, in my small way, making music or writing poems; medical staff whose hands take on the most difficult and tender of roles; the artist’s hands who can capture with a charcoal stick the enormity of what we might see if, after the fact, we can allow our creativity to take a step back and tell a story.

Phyllis Capello, who is a writer and musician, is a NYFA fellow in fiction I and a winner of an Allen Ginsberg Poetry Award. Her collection “Packs Small Plays Big” is from Bordighera Press, 2018. Cantastoria work (sing/storyteller) has taken her from Ireland-to-Istanbul. She has presented at the International Oral History Conference in Rome, Italy and has been a musician/clown since 1990 with Healthy Humor Red Nose Docs, as well as a member of the poetry/activist trio, The Ferlinghetti Girls. In 2023 she was honored with People’s Hall of Fame Award for teaching artistry for her work in New York City schools. Her poem “The Ballad of a Harlem Boy” appeared in the Fall 2023 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.

When Cure and Language are Inadequate, What Remains? Reflecting on bearing witness by Rachel Cicoria

Recalling the loss of her husband, Mike, Dianne Avey’s essay“Morning Light” (Spring 2023 Intima) reaches back a decade to a quiet September morning on Anderson Island in Washington. Avey, a writer and nurse practitioner, draws us, however, not to the moment of her husband’s death but to a “place of quiet morning light.” This liminal stasis exceeds cure and speech and, in my view, renders the “human” (as defined by technical and linguistic competencies) indeterminate. Yet, beyond our abilities to fix and to say, there remains “the only thing we can ever do”: being present and bearing witness.

Read moreOn "Feeling Blue" and Self Care: A reflection by neonatologist-poet Elizabeth Osmond

© Feeling Blue Amanda Hage Spring 2022 Intima

It is a challenging time to practice medicine. We are emerging from a global pandemic that is casting a long shadow. This has mingled with austerity for public service funding and a cost-of-living crisis. Members of many healthcare professions have been on strike.

Read moreCrossing the Line: The Power of Touch by Catherine Humikowski

A pediatric intensive care physician advocates for crossing the imaginary line and using the power of touch to comfort those in need.

Read moreThe Individual Nature of Care by Joanne Clarkson

A nurse examines a clinical encounter through her poetry and appreciates the individual nature of care.

Read moreOn Work-Worn Hands and Gestures of Love, a short essay by poet and educator, Joan Baranow

A writer and poet honors the memory of her mother by finding the parallels between her own work and the story of another mother and daughter.

Read more